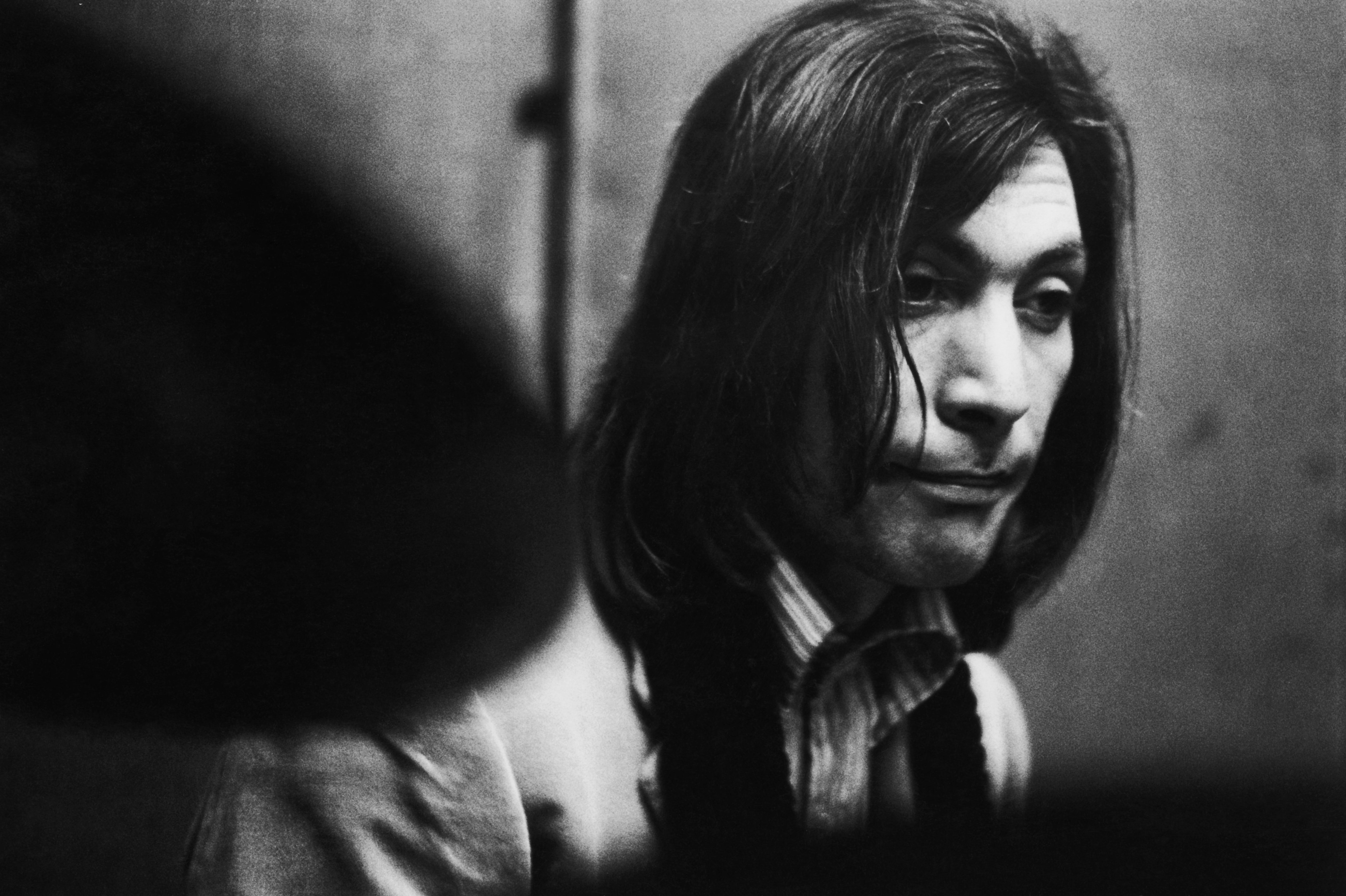

William Dege, now in his sixties, recalls being at the family business, the Savile Row tailors Dege & Skinner, when he first saw Charlie Watts in the flesh.

“I guess I was around 12 at the time, but even then I was surprised to find this man just wandering around the cutting room, which, seeing as it was behind the scenes, was pretty odd,” he recalls. “He was looking intently at this Army Flying Corp service dress jacket — we were making a replica of it for him. And when he left the cutter turned to me and said, ‘That was Charlie Watts, the drummer with The Rolling Stones.’ I think I probably said, ‘Who’s that?’ But it struck me even then how very stylish he was.”

Of course, Charlie Watts, who earlier this week died aged 80, had the money to indulge his interests. But these were also very particular, the products in some sense of a bygone, more securely masculine, perhaps more proper age. They in flouted the usual signifiers of the radical cultural revolution that birthed his band: horses, classic cars, first editions, rare records and, of all the things that might embody the staid establishment butting up against rock ’n’ roll rebellion, tailored suits.

The eye for a sharp two-piece was a gift from his father Charles, who took Watts for his first trip to a tailor’s in London’s East End. And Charles junior ran with that gift.

“Watts’s love of tailoring was a kind of representation of how he stood out from the rest of The Rolling Stones in many ways, not indulging in the excesses of the times as they tended to either,” says Dege, who’s company also made suits for the likes of The Kinks and, later, David Bowie. “And I think with reassessment now he’s come to be regarded as something of a style icon.”

By his own admission, Watts always felt “totally out of place” in the group, in terms of “the way I looked. Photos of the band would come back — I’ll have a pair of shoes on and they’ve got trainers [sneakers]. And I hate trainers,” he once noted. Even on stage, while the rest of the band would raid the dressing-up box, Watts would be sat at the back in something precise, trim and Mod-ish. Forget loud, forget eccentric, forget — heaven forfend — jumpsuits. He was the rock ’n’ roller who never felt the need to literally wear it on his sleeve.

Certainly Watts, who reputedly owned at least 200 suits, from Huntsman, Tommy Nutter, Chittleborough & Morgan and other Savile Row greats, together with countless pairs of shoes, all bespoke-made by George Cleverley, wasn’t notable for his tailoring purely in contrast to Jagger, Richards, Wood and Wyman. He wore it well of his own accord, standing out even when the other Stones dabbled in suiting for fashion’s sake — most famously, perhaps, when Jagger and his then wife Bianca wore matching white suits for their Studio 54 outings.

But then Watts had a template to reference. Always at heart a jazz drummer, Watts had the likes of Buddy Rich, Art Blakey and Gene Krupa’s similar high regard for good tailoring as his inspiration (while conceding some incredulity at how any of them actually played in a suit), with his love of the golden, pre-war age of Hollywood providing additional source material. He loved a contrast or pin-collared shirt. Check out how the color of his socks always — always! — echoed that in his shirt, too.

Watts called his taste “old-fashioned.” But it was more that he was faster than most to realize, as he once explained, that “when you get to my age … what works on a young boy won’t quite work on me. People don’t give the time or thought [to dressing well] anymore. It’s a bit of a lost world.” There’s little surprise that Watts never understood why anyone would use a stylist and have a look imposed by some stranger.

“What’s remarkable is how dedicated he was to tailoring,” argues Simon Cundey, CEO of Henry Poole, Savile Row’s oldest tailoring house. “Given the chaos of the 1960s and 70s, with the band overwhelmed by designers trying to get them into the most outrageous dress, Watts was all sartorial elegance. And somehow he managed to maintain that position. I’d often see him coming down the Row, always chauffeur-driven — I always thought it was strange how a man so into cars never learned to drive himself — and his driver always looked impeccable too.”

Watts made his sartorial mark most definitely in a double-breasted suit, a style — again, with period overtones — that turns most men into lost extras from Wall Street, or which only goes to emphasize their portliness. But small and always slender, with square shoulders, Watts’s frame allowed the double-breasted suit to hang perfectly.

“I think there are a lot of men still trying to model themselves on Watts’s preference for a double-breasted suit, and not all successfully,” laughs Cundey. “But while Watts had an exquisite love of detail, he was ready to gently bend the rules in tailoring too — to make a lapel just a little bit wider than it might usually be, for example — while still loving the tradition of it all.”

Indeed, Watts once opined on the hugely controversial subject of whether one should ever request a notch in the lapel of a double-breasted suit. That might make it interesting, but it was also out of kilter with the right way of doing things. He wouldn’t respect a tailor that let him make such a monstrous sartorial blooper.

“What was great about Charlie Watts was not just that he loved a suit, but that he was also a great advocate for Savile Row, appreciating the history, the culture, the differences of each house and each cutter within each house too,” says tailor Richard Andersen, ex of Huntsman and now of his own eponymous tailoring firm, who met Watts several times over the course of his career. “What really came across was that tailoring was a real joy for him. He gravitated towards the classic, but he always wanted to give some subtle kind of rock ’n’ roll quality to it. Savile Row is at its best when it cuts a suit to work with a certain personality. And Charlie Watts had personality in spades.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.