In 2017, Ezra* was a high school senior and the co-captain of his cross country team in Maryland. It was only his second year competing on the boys team, having moved over from the girls team at the beginning of his junior season. He had been a star runner on the girls varsity team his freshman year, skipping junior varsity completely, and began coming out to his friends and teammates as transgender before his sophomore season. It was then that he faced a choice: which team he would compete with for his sophomore year.

His school was accepting and he faced no institutional barriers to competing on the team that aligned with his gender thanks to living in one of the 16 states deemed “friendly” for trans athletes by TransAthlete.com, nor would he be starting testosterone for at least another year. During his freshman season, his team had suffered a devastating loss in the state championship race — so devastating, in fact, that one of his teammates broke the second place trophy in half. Ezra was seeded to be the top runner on the girls’ team his sophomore year and knew they could not win without him. The team was like his family, and he ultimately made the decision to run with them.

“It was challenging,” says Ezra, now 21 and a student at an Ivy League college. “I had just asked my entire school and my entire community to view me as male, to use he/him pronouns, to call me Ezra. I wanted there to be no residual perception of me as a woman. And then we would have sports assemblies and they’d call up women’s cross country, and I would have to march up there.”

Junior year, there was no question: before the season began, Ezra started testosterone and had top surgery. Joining the boys team meant leaving the girls who had been his biggest support system behind. The first time he’d ever heard someone use his chosen name was while he was running up a hill during a girls’ race, when someone cheered, “Go, Ezra!” He’d ridden the bus to all his meets with them.

“It definitely did feel like I’d given something up,” he says now of the decision to switch to the boys’ team. “And it was entirely worth it to me. I tried to frame it as a competitive opportunity to try to get back up there [and improve my times].”

By his senior year, Ezra was co-captain of the boys’ team and the underclassmen looked up to him. In retrospect, he looks back at the decision to switch teams as not only one of the most consequential moments in his athletic career, but as a culmination of sorts in the evolution of his identity.

“My experience as a trans person has been living with a lot of conflict constantly — conflict between how I see myself and how my body looks, conflict between how other people see me and who I know myself to be. Not being able to run on the men’s team takes that conflict and it puts it in the forefront of my mind, and it puts it in the forefront of everyone else’s mind. And that might be the absolute worst thing that you can do to a high schooler, whether it’s gender-related conflict or, or any other type of core, internal conflict,” Ezra says.

“So it was very important to me to finally have that alignment. And I think because [joining the boys’ team] was more or less the last thing I did to complete that alignment, it was very salient to me, wanting to sort of finish the puzzle of how you ought to be seen.”

There are probably hundreds of student-athletes like Ezra around the country, though we don’t hear about the lion’s share of them. Lost in the debates about biology and physiology and competitive advantages that surround trans kids in sports are the stories of the ones who are out there already — playing, winning, losing, thriving. And among the already small number of stories about trans athletes, the trans boys on the field are perhaps the most sparsely represented.

“It’s a very symbolic thing to not only be seen as masculine in a classroom or masculine walking down the street, but to be seen as something that is often thought of as the pinnacle of masculinity — to be able to out-lift another guy, to be able to flip someone, to beat someone in a race,” says Ezra. “Those are also things that tend to be misconceptions about trans people, wanting to not be seen as certain stereotypes of being trans and not wanting people to think that just because I was trans meant that I couldn’t keep up.”

When the coverage of trans kids who play sports focuses exclusively on the competitive aspect of the game, so much other context gets missed. Nearly 60% of kids participate in a sport at some point in their lives, and to deny trans kids the opportunity to do so is to deny them a formative experience that so many of their peers get to have. Competition is not the only reason kids play sports; other well-documented benefits include improved grade-point average, better focus, mental and physical health benefits, and a host of social and psychological rewards.

For trans kids, however, sports can do other things, too. They can give them a way to feel proud of their body, even before they have the words to articulate their gender. It also allows them to feel embodied, surrounding them with a team of people who accept and support them. With the rate of suicidality for trans youth being as high as 40% and research showing that providing gender-affirming care can reduce those feelings, it stands to reason that affirming trans kids in all areas of their lives will have positive effects on their mental health.

“A crucial part of identity development in any human is to be seen and reflected back. That sense of identity is what is going to carry people through most of the rest of their lives and protect them to some degree from traumas and experiences that can create other serious mental health problems,” says Ruben Hopwood, founder and director of Hopwood Counseling & Consulting in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The harm that’s done then in sports [is that] if they aren’t being affirmed, they aren’t being reflected back as who they know themselves to be, and people are actively saying ‘not only do I not see you, but I refuse to believe that what you say is true.’”

Unfortunately, this isn’t what we tend to talk about when we talk about trans athletes. The reality is that we only hear about trans athletes when they’re winning — girls like Andraya Yearwood and Terry Miller in Connecticut; Mack Beggs in Texas, whose story was thrust into the national spotlight when Texas forced him to wrestle against girls even after he started taking testosterone.

“That’s why everyone is assuming that there is some kind of domination of trans athletes and sports, because those are the only times we ever hear about them,” says Alex Schmider, Associate Director of Transgender Representation at GLAAD and Executive Producer of Changing the Game, a documentary about high school trans athletes that features Yearwood, Miller and Beggs. “That means there’s like 90% of a narrative that isn’t being covered. That lack of media representation is really establishing a false framework about what trans inclusion really means.”

Trans athletes are most commonly discussed in terms of the potential they have for competitive advantage, a discussion that disportionately impacts trans girls — and, in particular, trans girls of color. This hyperfocus by the media on trans women and girls is an issue both in sports coverage and in mainstream coverage, too. “The problem with trans men is that they’ve largely been invisible in the media,” Nick Adams, Director of Transgender Representation for GLAAD, says in the Netflix documentary Disclosure. “Certainly being invisible is a privilege compared to the type of transphobia that has been written into trans women characters. But I work with a lot of trans boys, and when they look to the screen to see themselves reflected back, they see almost nothing.”

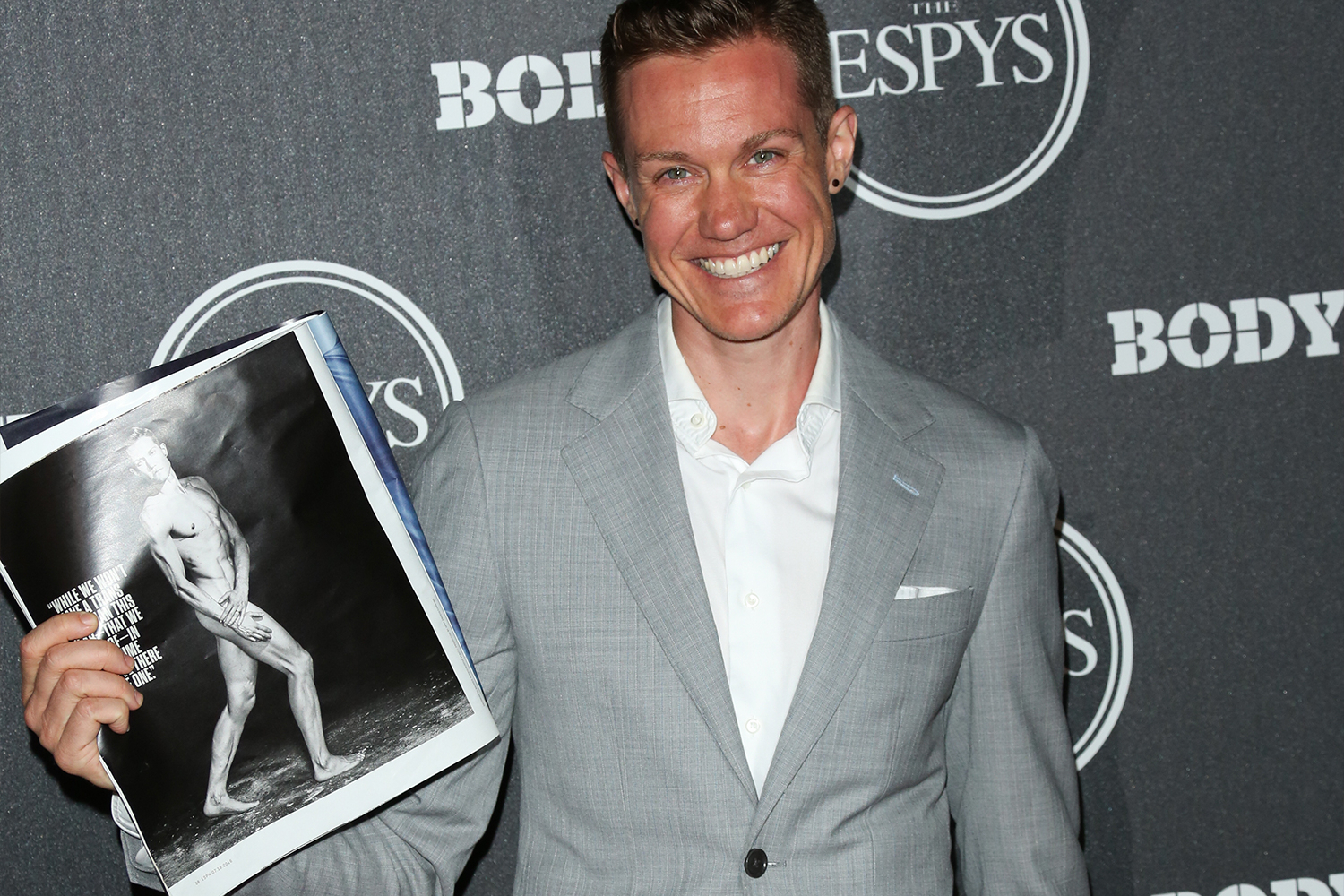

For many trans boys, especially those who live in more isolated areas, this invisibility has real impacts. Visibility allows people to see pathways for themselves, to believe that their goals and aspirations are possible. It’s why athletes like Schuyler Bailar, the first openly transgender Division I NCAA swimmer, and Chris Mosier, the first openly trans athlete to qualify for Team USA and who competed in the Olympic Trials in January 2020, are so important.

“It’s really cool to see representation, kind of like in politics, even if you don’t aspire to be them,” says John*, a 15-year-old cross-country runner from St. Louis, Missouri. “It’s just cool to see that they can, and that it could be possible.”

For John and many others like him, competing in the appropriate division is a double-edged sword: trans boys and trans men are not perceived as a threat when it comes to sports, which allows them to be able to slide through the system without as much controversy. At the same time, they can become an afterthought when it comes to advocacy or inclusion.

In the last legislative session, 17 states had 20 bills targeting transgender kids in sport. In 2021, at least six states have already introduced similar bills. “It was heartbreaking to hear how politicians were talking about people who were in the room, as if they were not people,” says Mosier, who founded TransAthlete.com, of the testimony being made to lawmakers in Idaho regarding House Bill 500. “Imagine being a young person hearing people talk about your identity as if you do not exist, or as if you are wrong, or you’re a monster.”

John testified against two anti-trans bills in Missouri last year. His parents pulled him out of school so they could have two minutes to “sit up in front of people and bare our souls and beg them to inform themselves,” John’s mother, Kelly, says. John socially transitioned at eight years old but has been stealth — meaning his peers, teachers and school administrators do not know he is trans — since middle school. This is not necessarily abnormal; a 2018 report from the Human Rights Campaign found that 82% of teenage transgender athletes were not out to their coaches.

Even though the Missouri State High School Activities Association (MSHSAA) has a policy allowing transmasculine athletes to compete on the boys’ team, John’s parents didn’t want to risk it, especially because of the anti-trans bills introduced in the state in recent years. It is his family’s way of protecting him against discimination after the Catholic youth sports league denied him the ability to play on the boys’ team when he first transitioned, forcing him to continue to compete with girls if he wanted to remain in their league.

These bills being introduced nationwide largely target transfeminine athletes. They are not intended to ban trans boys for the most part, but because trans boys are often an afterthought when they are drafted, it remains to be seen how things will play out if they are written into law. “All the conversation was about protecting girls in sports,” says Kelly. “But here’s my son. He’s not going to be on your girls’ team. What are you gonna do with that?”

One thing this attempt to ban trans kids from competing ignores is that most youth athletes — transgender or cisgender — will never compete at the most elite levels. They are just kids who want to play sports with their friends. That’s it. “It is complicated, but at the same time, it’s really not at all,” says Schmider. “Because when we’re talking about middle school, elementary school, even high school athletics, the basic premise should be that kids should be included in participating.”

By focusing so much on biology and physiology, the impact is the dehumanization of those kids. You take away their personhood by boiling them down to their body parts and hormones — things that especially don’t matter for prepubescent athletes. And while there is less concern about trans boys competing because they are not perceived as having an advantage in the way trans girls are, the lack of general understanding of transness still means that the cis people who are making or enforcing policies for trans youth only have these stereotypes to go off of.

When Aryn Butherus asked to switch from the girls’ basketball team to the boys’ during his sophomore year in high school in Wichita, Kansas, he says the administrator told him that trans people didn’t belong in sports because they had an unfair advantage. Butherus, who is 5’4” and was not taking testosterone at that time, was absolutely not at an advantage on the basketball court against cisgender boys who had gone through masculinizing puberty. Yet he was still denied the ability to play. Losing the sport that had been his favorite since childhood was “disheartening,” he says. “Just because I’m a trans athlete doesn’t mean I can’t be an athlete.”

Trans athletes face tough choices about competing all the time. For athletes who are connected to a sport without a male equivalent, like field hockey or softball, the option to switch to a boys’ team doesn’t exist. They have to choose between continuing to play the sport they love or living as their authentic self. For others, it can feel like everything they’ve been training for their entire lives, and the metrics against which they’ve measured themselves, have been shattered. Someone who has trained to compete with one set of times on a girls’ team, for example, has to adjust and work at a disadvantage when measuring themselves against the faster times that come with competing in a field of boys.

But the idea that trans boys cannot compete with cis boys on the field is demonstrably false. Mosier making Team USA means that he is literally one of the best in his category of all the men in the country. And Bailar, who competed against men while swimming for Harvard University, was ranked 443 out of all 2,983 Division I male swimmers — meaning he beat 85% of the men he swam against. “The narrative that we’re not capable of [being up there with cis men] at worst excludes trans boys from even stepping into sport,” he says. “And at best, makes them doubt themselves. No matter how you look at it, that narrative is toxic.”

When people ask Bailar how he plans to beat cis men, “It’s very simple,” he says. “The answer is, I did.”

Being able to compete against other boys can be affirming and formative even before an athlete is ready to come out as trans to the rest of the world. Samuel C. didn’t transition until he was 27, but he says his experiences competing on boys’ teams as a kid in Michigan helped him feel aligned with his gender even when the world around him didn’t see him as a boy. It was a resourceful solution for a kid who didn’t feel like he could be safe coming out as trans — under Title IX, girls are allowed to compete on boys’ teams if there is no equivalent team for girls, so Samuel sought out sports that didn’t have a girls’ team at his school: wrestling, football and baseball.

“It built the foundation for me to be able to have male friends and people that I could more easily identify with. Without putting words to it, I guess I was like, ‘I’m going to show you who I am rather than have to tell you,’” Samuel says of his time playing on boys’ teams before he was out as trans. “I could physically show my strengths, which helped me feel more masculine, it helped me feel right. It was telling myself I can compete with these guys, I can do this, I belong here.”

But it’s not just about winning and losing, or measuring one’s performance with numbers and charts. “Competition always looks like you’re trying to beat other people, but when it comes down to it, it’s really trying to beat yourself,” says Ezra. “That might be especially apparent in cross country, because even though it’s a team sport, a lot of it does come down to your individual times.”

In Changing the Game, you can see the difference for wrestler Mack Beggs. When he wins the State Championships after beating a girl, he looks dejected. His head hangs while the official raises his arm in victory, the girl who spent a year training to defeat him in the fetal position next to him, screaming in emotional agony. By contrast, at the end of the film, when he comes in third place wrestling against other boys, he’s glowing. The difference, of course, is simply that he was able to step onto the mat as his authentic self. “All I ever wanted to do was wrestle men,” he says, breaking into a smile. “And now that I am? It’s freaking dope.”

Perhaps even more important than the visibility of athletes like Bailar and Mosier are the stories of regular kids playing youth sports with their friends. Stories of discrimination, like that of Beggs, are “the only representation that we get right now. So having somebody in a positive way would be so helpful,” says Samuel. “For the majority of kids [cis or trans], we’re not going to be Schuylers or Chrises, they are so incredibly talented and good at what they do. In reality, that’s not going to happen for the majority of kids who just want to play sports. So I think having other trans kids represented in the lower level sports is so important.”

It’s why Schmider wanted to make Changing the Game. “In media, we see trans young people, particularly trans athletes, [have their] stories hijacked and taken from them to exploit narratives about why they should be excluded or discriminated against,” he says. “We made the film so that … trans young people get to see themselves as the hero they are in their stories, which we rarely get to see.”

Right now, trans kids are being used as a political wedge, but most just want the opportunity to play sports in a way that affirms their gender and sense of self, just like any other kid. And they’re out there, though we don’t often hear from them. Butherus says that attending track meets in Kansas, Oklahoma and Nebraska, he regularly encountered other trans athletes competing on their school’s team. “You’re going to have to face trans athletes. They’re there. We’re here. We’re not going anywhere,” he says. “You can’t get rid of us.”

One person interviewed for this story currently plays on a team with at least one other trans boy, and after Butherus’s difficult experience trying to participate in high school sports after his transition, he says a trans boy two years younger than him was able to play on whichever team he wanted — indicating that Butherus perhaps opened doors for the younger student.

“The success story is not [winning],” says Bailar. “The success story is stepping into the pool, it’s diving off the blocks, it’s stepping onto the field, and recognizing that you’re supposed to be there just like anybody else.”

When asked to describe his relationship with his male teammates, the answer comes to Ezra not in words, but in an image. It is from a video his team made for a pep rally his senior year. In it, the team of young men stand on a fallen tree over a river. They all have their shirts off, their arms around each other’s shoulders as they do a little dance together in a line. Ezra is there, too, top surgery scars and all, smiling. He is just one of the boys, right where he belongs.

“Sports have a big bearing on confidence. You can see your times, you can feel how much easier it’s gotten to run that loop that you did three weeks ago,” Ezra says. “And when you tie it into gender, gender dysphoria and the trans experience, [it] can really do a number on your confidence. So when you can throw in something that is a very literal physical reminder that you are capable, that you can be equal, that’s a really powerful thing.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.