This story was originally published on May 3, 2021.

The popular conception of lacrosse has been the same for decades. In 2010’s The Social Network, despite already being set amongst the most elite of Ivies, Justin Timberlake as Napster founder Sean Parker makes a point about power by recalling a revenge fantasy against the co-captain of his high school lacrosse team. In 1988’s Scrooged, the coiffed blowhard called in to replace Bill Murray’s character attempts to lighten the mood with the anecdote “My lacrosse coach used to say, ‘There is no ‘I’ in ‘T-E-A-M.’”

In other words, people think of lacrosse as a sport for the privileged elite. People who are rich, white and live on the East Coast, and whose high schools probably have a dress code. For a long time, the professional leagues in the U.S. haven’t actively discouraged that reputation, no matter the historical context of the game or the current demographics of players. Then, during the first year of the pandemic, when people were restless and more likely to take a chance on a sport they’d never watched before, the bubble of the prevailing narrative popped.

“My name is Jeremy Thompson from the Onondaga Nation. Today, I am going to be giving a Thanksgiving address, a land acknowledgment,” Thompson, a midfielder for Atlas LC, said during an August broadcast of a Premier Lacrosse League game. “And what a land acknowledgment means to me is giving thanks to everything here on earth that has been provided for us here as humans to sustain ourselves.”

If you’ve never heard of the Premier Lacrosse League before, remember the name, because you’ll hear it again soon. The PLL started in the summer of 2019 as a savvier alternative to Major League Lacrosse, the preeminent professional outdoor league in the U.S., but in December it was announced the two organizations had merged; in essence, the student had overtaken the master. But while the PLL has its sights firmly set on the future, it also has them set on the past — on the gap that has long existed in the modern incarnation of the sport, between the Native Americans who created it and the well-to-do English-speaking colonizers who adopted it.

“Lacrosse is, I believe, the closest marriage [between] a group of people and their spirituality than there is in any other game in the world,” Paul Rabil, co-founder of the PLL, tells InsideHook. “Native Americans have been playing lacrosse for centuries and that, to me, is the most compelling story related to sport and people in the world.”

Rabil is a rarity among sports bigwigs. Not only does he act as CMO of the PLL — which he founded with his brother Mike with the hope of building the next UFC, a non-legacy sport that has become a serious force — he’s a player himself, a star midfielder who will suit up for the Cannons Lacrosse Club, one of the eight teams in the league, when the season kicks off in June. But he’s a rarity for another reason as well: instead of seeing the fraught history of his sport as something to shove into a closet, he sees it as an opportunity to change the sport for the better and turn what has been a niche pastime into a national sensation.

According to Donald Fisher, Ph.D., who wrote Lacrosse: A History of the Game, one of the most complete histories of the sport, the story of lacrosse is like that of many Native American traditions: settlers adopted it, then shut out the originators.

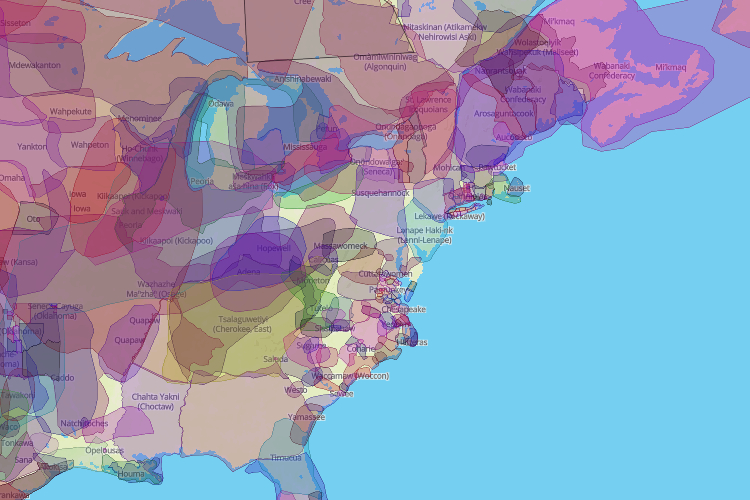

“A ball game that we call lacrosse today was played in many, many local forms centuries ago by Native people all over eastern North America, if you can imagine the eastern woodlands,” says Fisher, a history professor at Niagara County Community College. “So you’re talking people playing in the Great Lakes region all the way down to the deep South. Every cluster throughout eastern North America had their own game, but they’re all similar.”

Then in the 19th century, English-speaking Canadians who were trying to invent an identity made it the national game, and it became hugely popular almost immediately. “The more the game got commercial,” Fisher says, “there was a systematic effort to push Natives out of that world, essentially.” When the sport migrated to the U.S., first to upper-class society, then to college campuses, and slowly to suburbia, that trend was hardly reversed.

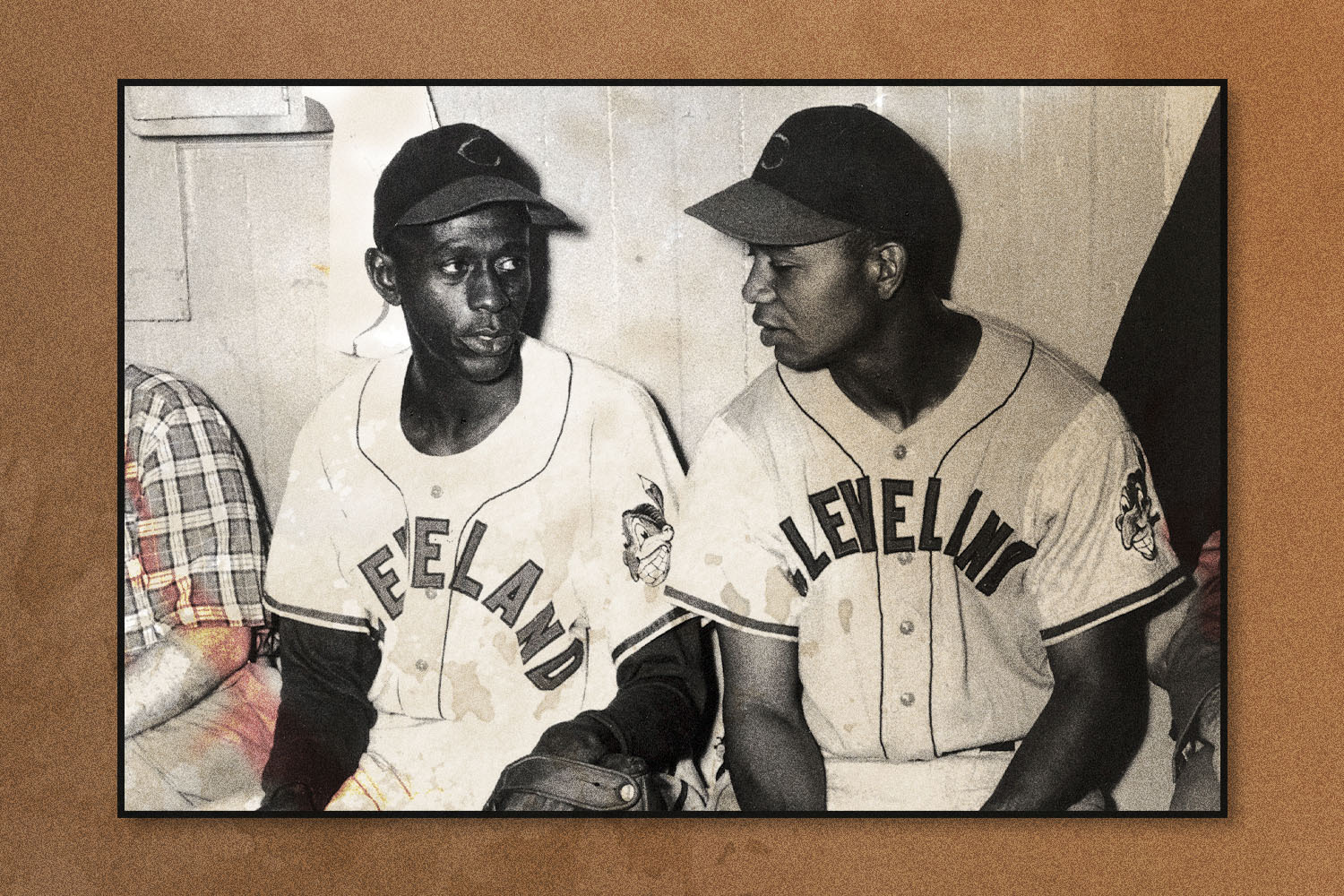

That’s not to say that the Indigenous people of North America have been completely sidelined. As Fisher notes, in 1936 the North Shore Indians made it to the championship game for the Mann Cup, the Super Bowl of Canadian box lacrosse. More recently, the Six Nations Chiefs, a First Nations team, has won the Mann Cup three times in the last decade. And the Iroquois Nationals, a team that represents the Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, have been competing in the international World Lacrosse Championship since 1990, winning bronze in both 2014 and 2018.

“Offhand, I can’t think of another sport that allows an Indigenous team to compete as a country,” says Fisher. “But again, considering lacrosse is of Native origin, it makes sense.”

It also makes sense that — in a time when NFL and MLB teams are changing their names and racial justice issues are front and center in American life — the PLL would choose to kick off a broadcast game with an Onondaga athlete giving a land acknowledgment, a ritual gaining steam in the U.S. that recognizes the Indigenous people of the area, usually spoken at the beginning of events. But while combining business and advocacy is par for the course in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the broader social justice movement it sparked, the PLL built advocacy in from the beginning.

“We did a land acknowledgment in our inaugural season too when we played in upstate New York at the University of Albany,” says Rabil. “We did so again to start our [2020] tournament, which was held in Utah, so we acknowledged the land for the full two and a half weeks that we played there. This year, we’ll be doing land acknowledgments at each of our 11 cities, and we started off by acknowledging some of the Native nations that currently are there and some that have inhabited the land at one point.”

To put together these declarations, the PLL works with Indigenous scholars, leaders and players to co-create the story or create the story entirely, as Rabil notes. In the most recent example, which was included along with the schedule for the 2021 season, the league tapped Lyle Thompson, who also plays on the Cannons, and who Rabil cites as one of the best players in the world alongside Lyle’s three brothers, Jeremy, Hiana and Miles, who are also pros.

“I want to acknowledge and send gratitude to our Indigenous ancestors for taking such good care of the land that we will be playing on,” Thompson wrote in the statement. “I also want to send thanks to the land and water protectors of the present day who are still fighting to preserve these lands and water that continue to provide for all of us.”

The term “water protectors” can also be read as “pipeline protestors,” as a number of Indigenous-led movements in the U.S. are attempting to block the construction and use of fossil fuel pipelines. When asked if that means the PLL is happy to wade into the “keep politics out of sports” debate, Rabil says he doesn’t think of the issue as political.

“I view this more as a humanitarian effort,” he says. In his mind, it’s not enough to have advocacy, there also has to be action. That means an official partnership with the Iroquois Nationals, which the PLL announced in January, as well as the continuation of the land acknowledgment rituals.

“I believe that what we’re discovering and rediscovering and educating and participating in related to the connection of lacrosse to Native American roots and the Haudenosaunee is not too different than what we want to continue to see happen at an American level,” Rabil says. “Facing that history and growing into a better place together.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.