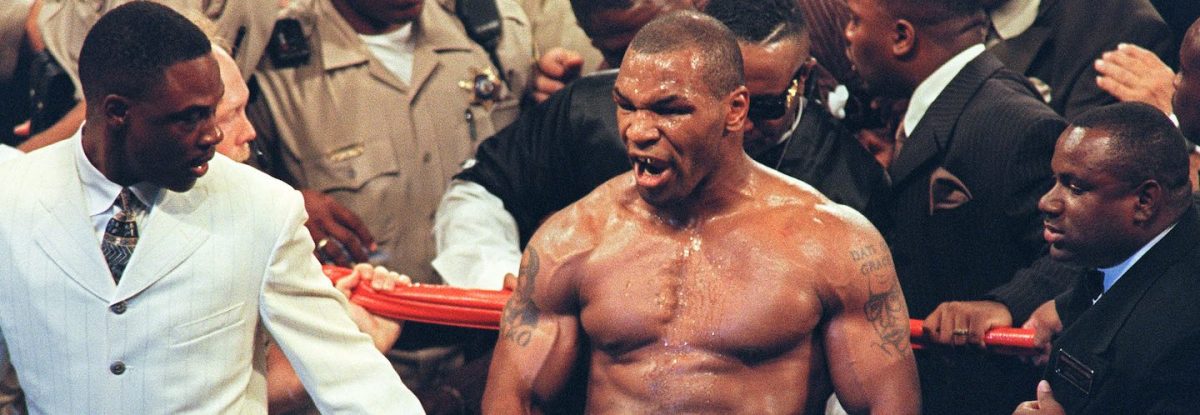

It’s been twenty years to the day since Mike Tyson officially went from power-punching ex-heavyweight champ to cautionary tale when he bit Evander Holyfield’s ear twice during their now infamous bout.

But when legendary trainer Teddy Atlas first met him, Tyson was just a kid with overwhelming potential.

“I had him since 12,” Atlas told RealClearLife.

By the time he met Tyson, Atlas was the protégé and then partner of Cus D’Amato, who had famously trained the heavyweight champ Floyd Patterson. His latest project went from a juvenile detention center to D’Amato’s gym in Catskill, New York.

“I would be in the gym every day,” Atlas recalls. “Cus would come once a week: ‘Let me see how the project’s going, how this future champ’s coming along.’”

Their time together came to an end after a 1982 incident between Tyson and a young girl who was a relative of Atlas’ wife. (In response, Atlas confronted Tyson with a gun.) Tyson went on to captivate the world, first as the youngest heavyweight champ ever at just 20 in 1986 and then over time for all the wrong reasons with a prison sentence for rape and the disturbing antics during his June 28, 1997 fight with Holyfield.

Atlas later trained two men who won heavyweight titles themselves, as well as becoming a boxing analyst for ESPN. But there’s a lot of what ifs when it comes to the talented Tyson, who had an array of physical gifts few boxers can approach. “God was very good to him,” says Atlas. “If we’re just talking about pure talent, he’s as good as anyone.”

In particular, three qualities set Tyson apart:

The hat trick of hands. There are three things a boxer most wants as a puncher, and Tyson had all of them. “He had a combination of quickness, speed, and power, which is not common.” (Atlas cites Manny Pacquiao as one of the other boxing legends boasting this combo.)

A basher from both sides. “As far as punching ability, he’s like a Mickey Mantle in baseball. He could hit from either side of the plate just as well. Again, not common. Guys like Ernie Shavers, great puncher, but all on the right side. Tyson, either side of the plate.”

A superior approach to being small. Tyson stands only 5’10”. By comparison, Joe Louis was 6’2″, Muhammad Ali was 6’3″, and the Klitschko brothers are 6’6″ and 6’7″. (Vitali has an inch on “little” brother Wladimir.) Yet this didn’t matter to Tyson: “Something that could have been a detriment turned out to be a strength.

“He would get underneath a taller guy’s punches and guess what? While they were punching down they left an opening because you’re really not supposed to punch down: you leave an opening to your chin.” (It’s true: Extend your arm straight out and see how your arm and shoulder protect your chin. Not the case when you lower it.)

Atlas says they fully exploited this, telling Tyson he was “quick enough to explode three punches in that opening.” He recalls his instructions to Tyson on breaking down big men: “Get under a guy’s punch and then, when you know a guy’s gonna back away from the pressure, you little friggin’ cyclone, you’re going to anticipate that and be stepping forward and throw a punch not where his chin was, but three feet behind that. And he’s gonna walk right into it.”

(You can appreciate all of Tyson’s gifts in the demolition of Trevor Berbick, who had a good four inches on him.)

But Atlas says Tyson had a major limitation: “He was as good as his opponent was tough.”

In his former mentor’s estimation, Tyson crumbled in the face of resistance. “When he could overpower you with his brilliance of pure ability and run you over like a monster truck, he was spectacular. But when resistance comes in, when the talent’s comparable, it’s about character.”

This is an area where Tyson was lacking.

Atlas recalls Tyson’s sparring sessions when he was a teenager as displaying incredible potential, but also one worrying habit. “We used to have to pay sparring partners because he punched so hard that he knocked them out. Then every so often we’d get one that he couldn’t knock out.” At which point Tyson would engage in what Atlas calls a “silent agreement.”

Essentially, a silent agreement is when boxers hold each other, with both taking a break from fighting for rest and recovery.

While Atlas first blamed Tyson’s holding on “immaturity,” he saw no improvement no matter how many times he told Tyson to quit that habit: “I said, ‘Stop making silent agreements. Because one day you’ll get a guy who won’t sign a contract.’”

This is what happened when Tyson ran into boxers Atlas terms “pros,” notably Holyfield. Nicknamed “The Real Deal,” Holyfield repeatedly proved it throughout his lengthy career. He fought Tyson twice—both bouts ending in Holyfield wins. Indeed, Iron Mike didn’t go the distance in either.

“Some of those punches he landed in that first fight with Holyfield would have knocked out a lot of pretty good fighters. But they bounced off the chin of a guy that had that special resolve, that character. A real pro. Tyson was the greatest when he didn’t fight a real pro.”

This isn’t to say that Tyson would quit entirely when confronted with obstacles… but he often stopped putting in the exhausting work of continuing to attack: “Did [Tyson] show heart when he took an ass-beating from Holyfield? Yes. He was a ‘game quitter.’ A guy who doesn’t give up, doesn’t fall down, he’s game with those punches. But he stops trying to win.”

Tyson lost a total of six fights during his career. Four came against fighters who spent some time as heavyweight champ: Buster Douglas (who famously gave Tyson his first loss, dropping his record to 37-1), Holyfield (twice), and Lennox Lewis.

Then there are the defeats in Tyson’s final two fights. Tyson was 38 at the time of his bouts against Danny Williams and Kevin McBride, men who— shall we say—will only enter the Boxing Hall of Fame if they buy a ticket.

Both knocked Tyson out before the seventh round. It was a particularly shocking result against McBride. The “Clones Colossus” once fought against Michael Murray when Murray was in the midst of losing 17 out of 18 fights.

The one exception? Murray beat McBride… by knockout.

“Tyson lost to an Irish kid, Kevin McBride,” Atlas says. “All of the fighters who were great fighters, they never lost to a Kevin McBride. It couldn’t happen.”

Atlas compares Tyson to a fighter who showed character both inside and outside of the ring. “What made Ali great was he was brought up to face things, whether it was the bully who took his bike or a decision to die professionally and stick by his beliefs,” Atlas said, referring to Ali’s refusal to join the draft, which cost the greatest boxer of his generation three-and-a-half years of his career. “He was willing to make that stance, right or wrong.”

By contrast, Tyson “used to hide when bullies would come around his neighborhood.” Before breaking big, he was a neighborhood bully himself.

Atlas concludes that Tyson was “fabulously talented, but just as fabulously flawed and weak when it came to the mental side.”

Unsurprisingly, Atlas says when ranking Tyson among the greats: “Where do you put him in the top 10 list? He doesn’t belong there. He’s not near there.”

Ultimately, Atlas considers Tyson a “meteor” while Ali, Louis, and Rocky Marciano are “planets.”

Why? “Planets last.”

Yet Atlas understands why Tyson excited people in a way more accomplished boxers never did as he turned in “sensational performances, no doubt about it.” Iron Mike may have been a meteor, but he was a meteor that demanded attention: “When he was moving, he was pretty fun to watch.”

See some of Tyson’s most meteoric performances below and, at bottom, watch Tyson explain the reason he finally apologized to Atlas after decades of tension and why the trainer was “extremely important” to him.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.