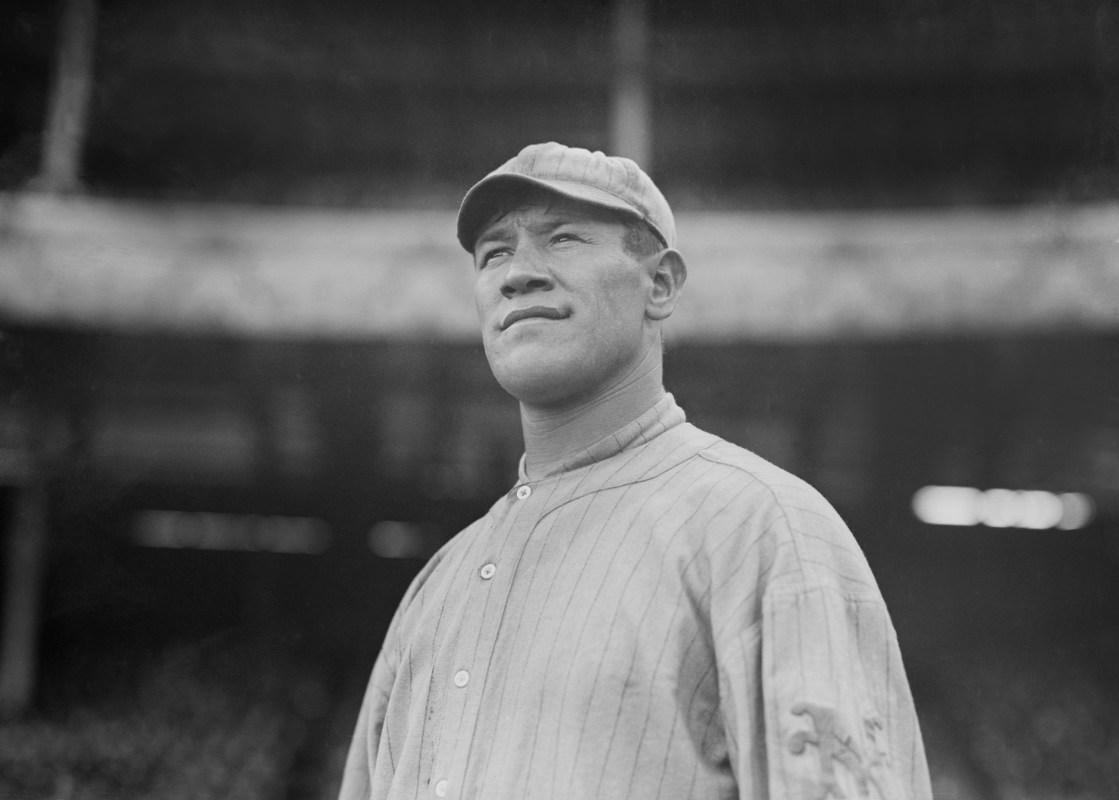

Arguably the greatest (and unquestionably most versatile) athlete in American history had his 130th birthday on Memorial Day, May 28. Or maybe not. While Jim Thorpe has often been reported as being born in 1888, 1887 is cited too and regardless there’s been a debate if the 28th was the exact day on which he was born. That uncertainty suits Thorpe. He is a strangely mythic figure—the young man who seemed to excel at whatever sport he attempted, including track and field (two Olympic golds for decathlon and pentathlon), football (he’s in both the College and Pro Hall of Fames) and baseball (six seasons in the majors).

Thorpe feels as Ruthian as the Babe: a star athlete from long ago who seems impossible in our modern era.

Except the Bambino suddenly is possible again, with Shohei Ohtani doing this at the plate:

And this on the mound:

This is a look at what Thorpe actually achieved, those who have come closest to matching his marks and how an aspiring Thorpe would be handled today.

“Kill the Indian, Save the Man”

Whether it happened in 1887 or 1888, Thorpe was born into a world largely unrecognizable to us, in terms of sports and in more important ways.

-The first modern Olympics didn’t happen until 1896. (It featured only 14 countries. In 2016, the International Olympic Committee recognized 206 member nations.)

-The first World Series wouldn’t be played until 1903. (Ruth reached the majors in 1914.)

-The NFL wouldn’t be founded until 1920. (Red “The Galloping Ghost” Grange, who became a national sensation at the University of Illinois after scoring four touchdowns and racking up 262 yards in the first quarter against Michigan, didn’t reach the NFL until 1925.)

It was also a time when a Native American boy who lost his parents (as Thorpe did) might wind up at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. These institutions aimed to culturally assimilate Indian children, forcibly if necessary. The founder of the first Indian School proclaimed the way to handle someone with Thorpe’s heritage was this: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Thorpe attended Carlisle from 1904 to 1913. (Carlisle Indian School only closed in 1918.)

During Jim Thorpe’s lifetime, there were more opportunities for a Native American athlete than, say, an African American. (Jackie Robinson didn’t break Major League Baseball’s color barrier until 1947.) But it should not be forgotten how much racism he faced, even if it was just casually injected into the coverage of his achievements. (A Boston newspaper wrote that the Harvard-Carlisle game showcased an “an unequal conflict between the white man’s brawn and the red man’s cunning.”)

The Talented Mr. Thorpe

Carlisle brought Thorpe to the attention of a coach who continues to lend his name to youth football: Glenn “Pop” Warner. Warner recognized that Thorpe conquered seemingly every sport he attempted. That versatility was particularly noticeable on the football field, as Thorpe played halfback/defender/punter/place-kicker.

Then Thorpe traveled to Stockholm and transformed himself from an American celebrity to a global one.

Thorpe’s height is usually listed as 6’1” at a time the average male in the U.S. stood 5’7”. (We’ve now reached about 5’10”.) Thorpe is believed to have weighed 185 pounds at the 1912 Olympics. His size is similar to track legend Carl Lewis, the winner of nine gold medals who stood 6’2” and was listed at 176 pounds.

Of course, Lewis reached his first Olympics 72 years after Thorpe competed. Whether in terms of stature or skill, Thorpe was generally generations ahead of his competitors.

A Decathlon Dominated

1912 was the Olympic debut of the decathlon. It remains a major event to this day, making a celebrity out of Bruce (now Caitlyn) Jenner in 1976. Ashton Eaton won the decathlon in 2012 and repeated in 2016. In 2012, Eaton topped three events but also struggled at times, missing the top ten in the shot put and not even cracking the top 20 in the discus. The following Olympics, he only took two events outright in earning his second gold.

This is how Thorpe fared in the ten: 100 meters (third), long jump (third), shot put (first), high jump (first), 400 meters (first), discus throw (third), 110 meter hurdles (first), pole vault (third), javelin (fourth) and 1500 meters (first).

1912 was also the debut of the pentathlon. Thorpe came even closer to perfection: long jump (first), javelin (third), 200 meters (first), discus (first) and 1500 meters (first).

In summary: 15 total events, nine firsts, nothing worse than fourth, two golds.

The double gold medalist returned to the U.S. and just two months later led Carlisle to a 27-6 victory over Army, scoring two touchdowns and kicking three field goals. (Army featured a player who would go on to be a general and then U.S. President: Dwight Eisenhower. Thorpe later praised him: “Good linebacker.”) For the season, Thorpe rushed for 1,869 yards on 191 attempts—a staggering 9.8 yards per rush—as Carlisle went 12-1-1. (That rushing total would have ranked third in the NCAA this past season, with both players ahead of Thorpe having dozens more attempts.)

Thorpe also scored 25 touchdowns and collected a total of 198 points. (This would have ranked him at second and first, respectively.) To the surprise of no one, he earned his second All-American selection.

The revelation in 1913 that Thorpe had been paid for minor league baseball games ended his amateur status and caused him to lose his gold medals. The medals were eventually restored, but not until decades after Thorpe’s 1953 death. Worse, he never should have lost them in the first place. To punish Thorpe for breaking their rules, the IOC blatantly violated them. (Allowed only a month to challenge an athlete’s status, they took half a year for Thorpe.)

There was nothing left for Thorpe to do but make some money.

The Professional

Thorpe’s combination of fame and absurd talent allowed him to compete in a variety of arenas. He signed a $6,000 per season deal to play baseball with the New York Giants. He would also be able to pick up $250 per game playing professional football in the precursors to the NFL. (By comparison, it was believed he earned only about $2 per game playing the minor league baseball games that cost him his golds.)

To put these sums in perspective, in 1915 the average income for an America man was $687. Thorpe was well paid, but by no means making modern athlete money. MLB’s Mike Trout earns $33.25 million this season while the NFL’s Matt Ryan collects $30 million. These salaries are more than 400 times the roughly $73,000 earned by the average American household—a haul Thorpe never began to approach. This helps explain Thorpe’s financial struggles later in life, including working as a ditch digger.

Baseball proved that Thorpe wasn’t necessarily great at everything he attempted. He reached the majors in 1913 and made his last appearance in 1919. He played a total of just 289 games over six seasons—that doesn’t even add up to two full seasons of everyday play. For his career, he showed some speed (29 stolen bases and 18 triples), very little power (seven home runs) and ended up with an average of .252. He played all three spots in the outfield and also started at first base. His lone appearance in a World Series embodies his unfulfilled potential: Thorpe technically appeared in a game but never actually got to bat as he was lifted for a pinch-hitter after a pitching change.

Yet even here he showed he could compete and even excel. In Thorpe’s final season, he played 60 games for the Boston Braves and batted .327. Edd Roush, the NL batting champ that year, only hit .321 (albeit over 133 games).

Thorpe also continued with football. He played for the Canton Bulldogs from 1915 to 1917 and again from 1919 to 1920, three times winning what was billed as pro football’s highest title. He went on to serve as the first president of the NFL when it was founded in 1920. (This was more for his fame than his management skills—Joe Carr took over the job in 1921 and held it until 1939.) Thorpe played for franchises including the Cleveland Indians football team, the Oorang Indians (a team based in Ohio), the Rock Island Independents (a team based in Illinois), the New York Giants (yes, he played for both the baseball and football team with this name), the Canton Bulldogs (again) and the Chicago Cardinals before his final retirement in 1928.

Records of these playing days are, to put it mildly, incomplete. The Pro Football Hall of Fame notes that Thorpe played 52 games and collected six touchdowns rushing and four touchdowns passing. (They list him as playing 12 seasons total, including his pre-NFL days.) Pro Football Reference also credits him with three extra points, kicking four field goals, having 37 starts among those 52 games and earning First Team All-Pro in 1923. (The Hall of Fame named him to their All-1920s Team as well.)

Though Thorpe played only a single game for the Cardinals (now in Arizona), they still celebrate him on their website: “While Thorpe’s exploits tend to be exaggerated with the passing years, there is no question he was a superb football player. He could run with speed as well as with bruising power. He could pass and catch passes with the best, punt long distances, and kick field goals either by drop kick or place kick. He blocked with authority and on defense was a bone-jarring tackler.”

Quite simply, we lack specifics on a great deal of Thorpe’s athletic career. (This isn’t even to get started on side sports ranging from Thorpe continuing to compete in minor league and semi-pro baseball to barnstorming with his “Jim Thorpe and His World Famous Indians” basketball team to being an accomplished ballroom dancer.) We do know that Thorpe was:

-An absurdly good college football player

-A historically superb competitor in track and field

-Apparently a great pro football player (even if we have to rely on accounts and honors rather than raw numbers)

-An unspectacular player in Major League Baseball (though just competing at baseball’s highest level becomes rather remarkable when paired with his other pursuits)

In short: Much like Babe Ruth, Thorpe’s a mythic figure who lived up to the myth. Leading to the question: Has anyone else approached (or even equaled) Thorpe’s varied legacy?

These are the contenders as divided by category.

Insufficiently Athletic Champs. Walter Ray Williams Jr. is likely the greatest bowler ever, with records including the most PBA career titles. He is also a remarkable horseshoes player, racking up a number of titles there too. Yet impressive as these feats are, he didn’t ever have to roll a strike after being blindsided by a defensive end or toss a ringer after being drilled in the ribs with a fastball.

Good But Not Greats. They managed to play multiple sports at a major league level. A classic example is Gene Conley. The 6’8” Conley was a solid pitcher: 91-96 over 11 seasons with a 3.82 ERA, making three All-Star teams and even winning a World Series in 1957. (Conley’s contribution was limited, as he pitched 1.2 innings and gave up two earned runs.)

“Long Gene” carved out a unique place in American sports by also winning three straight NBA championships with the Boston Celtics from 1959 to 1961. He ultimately played a total of six NBA seasons, averaging 16.5 minutes, 5.9 points and 6.3 rebounds. Even so, Long Gene clearly won that World Series because his teammates included Hank Aaron, just as he picked up those NBA titles because he shared a locker room with Bill Russell.

Far more athletes managed just a taste of two leagues, like Tom Brady’s former University of Michigan teammate (and QB competitor) Drew Henson. Henson never fulfilled his seeming potential but did wind up having an impressively symmetrical career: he threw one career TD in the NFL and collected one career hit in MLB.

Olympian and a Pro. “Bullet” Bob Hayes played for the Dallas Cowboys from 1965 to 1975, twice leading the NFL in touchdown catches and yards per receptions while winning the Super Bowl in 1971. Hayes also picked up two golds at the 1964 Olympics, winning both the 100 meters sprint and the 4×100 meter relay.

Hayes matches Thorpe step for step in many ways: They’re both Pro Football Hall of Famers with a pair of golds. Yet he never played a second pro sport as Thorpe did, not to mention his Olympic success was due to ridiculous speed while Thorpe showed off an array of gifts. (To be fair, perhaps if he’d tried Bullet Bob would have proven a natural shot putter, long jumper, high jumper, pole vaulter, javelin thrower, etc., just as Thorpe did.)

Great at One, Not So Much at Another. Michael Jordan’s 1994 season batting .202 with the Birmingham Barons is the classic example. (To give Jordan credit, he stole 30 bases and what did we really expect from a 31-year-old who hadn’t seriously played the game since he was a teenager? Plus there was this in an exhibition game.)

Far more often, athletes just pick one and forget the other. John Elway played for the Oneonta Yankees in 1982, batting .318 in 42 games before forcing a trade from the Baltimore Colts to the Denver Broncos and deciding to keep being a quarterback, after all.

Danny Ainge is an interesting case of someone who gave two sports a shot at the major league level. He played 211 games for the Toronto Blue Jays from 1979 to 1981. Sadly, he didn’t play them very well, posting an average of .220 with two home runs and a slugging percentage of just .269.

Ainge then switched to the NBA and had more success, making an All-Star team and winning two titles with the Celtics. (He is the mastermind of the franchise today, earning another title and Executive of the Year.)

Great at One, Potentially Good at Another. In 1962, Dave DeBusschere started careers in both MLB and the NBA. Things turned out pretty well on the basketball side, as he made five First Team All-Defensive teams, eight All-Star teams and won two titles with the Knicks before winding up in the Hall of Fame.

His baseball career ended after two seasons with a record of 3-4. Still, his career ERA was a solid 2.90 and he even threw a shutout. Could DeBusschere have been a star in both sports? Or would trying have just permanently stunted his basketball? (His first two NBA seasons were the worst of his career.)

Lionel Conacher also falls into this category. The “Big Train” was basically Thorpe, Canada style. The Hall of Famer in hockey played in the NHL from 1925 to 1937, making three All-Star Teams and winning two Stanley Cups. The “Big Train” also won the 1921 Grey Cup playing football with the Toronto Argonauts and an International League championship with the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team. (It was considered to be at the high minor league level, but not quite major.)

Short But Very Sweet. Bo Knows. If you’re of a certain age, those two words conjure up images of a man who could seemingly do anything. A Heisman winner in college, Bo Jackson’s NFL career was surprisingly brief. He played only four seasons, scoring 18 career touchdowns (16 rushing, two receiving) and accumulating 3,134 yards from scrimmage. (In 2006 alone, LaDainian Tomlinson scored 31 touchdowns and racked up 2,323 yards.)

Bo reached his lone Pro Bowl in 1990, when he played in his first and last playoff game as he suffered an injury that ended his football career.

Jackson stuck around longer in baseball, lasting eight seasons. Yet there too his greatest moments came before 1990. In 1989, he played 135 games, batting .256 but slamming 32 home runs, driving in 105 RBI and stealing 26 bases while making the All-Star game (and promptly winning All-Star MVP). He retired with a career average of .250, having hit 141 home runs and stolen 82 bases.

While the overall numbers aren’t overwhelming, Jackson had a genius for moments when he looked like he wasn’t just the best on the field but playing a different sport altogether. He had a run of at least 88 yards in three of his four NFL seasons. And in baseball, he literally defied gravity:

Then there was the time his head took on his bat and his head won.

If he’d stayed healthy, remarkable things might have happened. But Bo failed to know longevity so it was another baseball/football player who came closest to Thorpe’s legacy.

Two for Two (Almost). Deion “Prime Time” Sanders never quite captured the public imagination the way Bo Jackson did. This was not for lack of effort. Witness his album Prime Time, including the single “Must Be the Money”:

He also hosted Saturday Night Live. And naming his daughter “Deiondra” suggested a human being who really, really wanted people to pay attention already.

Yet far too often, he gets remembered as that football player who hated to make tackles. (It doesn’t help that, when this is pointed out, Deion tends to be hilariously sensitive about it.)

This overshadows that from 1989 to 2000, Deion had an incredibly successful NFL career. (His return to the NFL in 2004 and 2005 was less so, but by that point, the legacy had already been built.) Six First Team All-Pro picks, eight Pro Bowls, two Super Bowls. While his Hall of Fame status is built around his play as a defensive back, he also returned punts, kickoffs and even played on offense a little. This is a man who scored touchdowns off interceptions, kick returns, punts, receptions, a fumble recovery and as a rusher.

As a football player who could contribute in a variety of ways, Deion doesn’t need to take a backseat to Thorpe or anyone else. This was clear even in college, when he won the Jim Thorpe Award as the nation’s top defensive back.

Beyond this, Deion had a surprisingly solid baseball career. While his career average is .263 and he never played more than 97 games in a regular season, in 1992 he batted .304 with 26 stolen bases and a league-high 14 triples. That year Prime Time nearly wound up not only a World Series champ but Series MVP, batting .533 with five stolen bases.

Throw in Deion’s becoming the first man to hit a home run and score a touchdown in the same week and he was just an Olympic medal or two from Thorpe terrain.

A Thorpe Today

It’s been years since anyone seriously tried to play in multiple major leagues simultaneously. (Deion gave up baseball in 2001 and fully retired from the NFL in 2005.)

The challenges can be understood by looking at Shohei Ohtani. By pitching and hitting between starts, it feels like he’s pursuing two separate professions (even if it’s all baseball). And that’s a remarkable feat for reasons including:

–Systemic Specialization. Dr. David Geier told RCL he suspected America was producing potential Ohtani’s: “At the high school level, so many of a team’s best pitchers are probably also their best batters.” (An orthopedic surgeon and author of That’s Gotta Hurt: The Injuries That Changed Sports Forever, he has worked with the medical teams for the St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Rams.) But players don’t get the chance to develop all their talents: “They don’t let these guys bat—they basically become pitchers.” (If a prospect is touted as a future #1 starting pitcher, you don’t want him destroying his shoulder taking an awkward headfirst slide or slamming into the catcher.)

Thorpe came along at the moment when sports were still largely wide open. It was a time a young man could impulsively try the high jump (as Thorpe did in 1907) and some other track events and within five years be an Olympic gold medalist. Indeed, Thorpe first pole-vaulted and threw a javelin the same year he took gold.

Athletes were allowed to attempt different things. They often had to try different things—they couldn’t make a living off one sport. (And if you did play a sport, you were expected to fill a lot of roles. Witness Thorpe being an all-world halfback but still kicking and going out with the defense.)

Letting an Ohtani pursue two very different skills goes very much against the grain today. And that puts a unique pressure on him.

–No Space for Slipping. Ohtani was widely mocked for his spring training performance. That criticism has been silenced, but the fact remains if Ohtani starts struggling at one of his roles while still excelling at the other a whole lot of people will urge him to focus already.

Once a player develops a problem, it can be hard to make a fix. The pitching guru Michael Witte told RCL that even if you recognize flaws in a player’s mechanics, you may still not be able to repair them: “That is a talent itself, to be able to change.” Ohtani has shown he can do exactly that. This season he eliminated a leg kick from his swing and almost instantly saw results, whereas another player making that move could find themselves heading permanently to the minors.

Of course, while Ohtani fills two different roles, he performs them both for the California Angels. And this brings us to the biggest challenge for a new Jim Thorpe.

Why Would a Team Want to Share?

As noted, it’s possible for baseball and football players to earn $30 million a year. At his peak, the track legend Usain Bolt did too. It can even be surprisingly lucrative to be an elite decathlete today: Ashton Eaton collected $750,000 from Nike for setting a world record back in 2012 and the money’s only continued to pour in.

No longer would a Thorpe feel a financial pressure to pursue multiple sports. Indeed, now players are so valuable their own teams do their best to restrict their actions. That’s why pro contracts generally either outright ban hobbies like auto-racing and hang-gliding or (in the NFL’s case) forbid “any activity other than football which may involve a significant risk of personal injury.”

Which makes sense: Bo Jackson was hurt playing football, but he didn’t magically remain in perfect baseball health for the other half of his career.

To be like Jim Thorpe, an athlete requires sufficient clout to demand a contract that lets them do what lesser players wouldn’t even get to attempt. (Ohtani had the option of remaining in Japan or playing for a number of interested teams and used this leverage to ensure he’d only sign with a franchise that let him hit and pitch.)

A Thorpe today would not only have to be capable of playing multiple sports, but potentially be able to pursue them at such a ridiculously elevated level that every wish was the command of two teams. (Otherwise, they’d sign players of roughly equal talent who’d eagerly devote themselves to that franchise alone.)

How would this look in practice? Think LeBron James signing with the Lakers… but also resuming a high school passion and playing some tight end for the Chargers too.

(Geier said that LeBron already takes basketball recovery so seriously that he reportedly “sleeps 10, 11 hours a day”—there literally may not be enough hours in the day for him to attempt two sports.)

The Final Requirements

To summarize, to be a Thorpe today demands someone with:

-The athletic gifts to split his or her time and still keep up with competitors obsessively focused on a single sport.

-The star power to force teams to risk having their prized player injured playing a sport that has nothing to do with their franchise.

-The personality to find being pulled in multiple directions at all times to be exciting, not crushing.

Thorpe’s physical gifts are often praised, but it’s worth remembering how mentally strong he was. While even he would doubtless struggle to match his marks in this era, he would have welcomed the challenge. As he put it: “They just keep coming, but that’s what keeps me going.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.