John Thompson, Jr., had the job. Now he needed to meet with the priest. It was 1972 and Thompson, a 30-year-old high-school coach and ex-college and NBA player, was about to be handed the reigns to Georgetown University’s men’s basketball team. The priest in question was Father Robert Henle, the President of the university, who would make the head coaching hire official. When they met, Thompson asked Henle what his expectations were for the team, which had finished the previous season with a record of 3-23.

“I’d like to periodically make the NIT, and go to the NCAA tournament once in a while,” Henle said.

Thompson, who vividly recounts this meeting in his new, posthumous autobiography I Came As a Shadow, was amused by the Jesuit’s answer.

“‘I think we can do that,’ I replied with a straight face,” writes Thompson. “Inside, I was laughing. That’s all y’all want? When you’re 3-23, periodically going to the NIT looks like the Promised Land.”

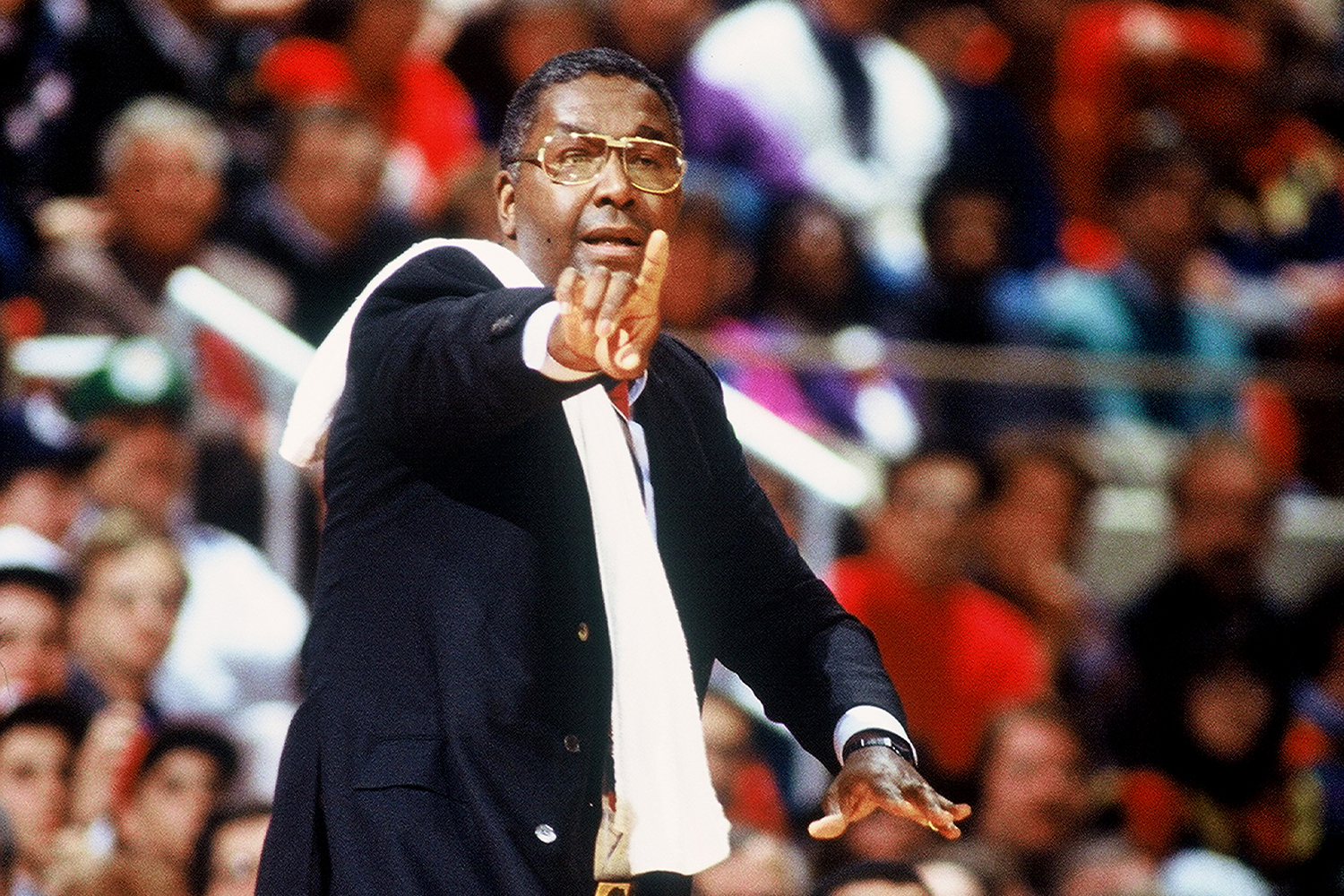

In the 27 seasons that followed, John Thompson brought Hoya fans to his Promised Land. Thompson’s squads qualified for the NCAA Tournament 20 times, appearing in four Regional Finals and three Final Fours. In 1984, Georgetown reached the pinnacle and won the National Championship, making Thompson the first Black head coach in NCAA history to do so (a superlative that Thompson famously took to task in interviews).

In 1999, Thompson stepped away from coaching, leaving behind a basketball program widely regarded as one of the nation’s best. In 2020, an assessment of that same program raises the question: What the hell happened?

In the two decades since Thompson vacated the sidelines, Georgetown — under the direction of Craig Esherick (1999-2004), Thomspon’s son John Thompson III (2004-2017) and Patrick Ewing (2017-present) — has appeared in the NCAA Tournament just nine times, with zero appearances since 2015. Of those nine appearances, only one — a remarkable run to the Final Four in 2007 — recreated the magic of the best campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s. To make matters worse, Georgetown has picked up a conspicuous habit of playing Goliath in the postseason, losing a series of recent tournament matchups to heavy underdogs like Steph Curry’s Davidson, Ohio University and — avert your eyes, Hoya fans — 15th-seeded Florida Gulf Coast University. The Hoyas, in a sense, have become the merely satisfactory team that Father Henle once pined for.

Thompson, who died in August at the age of 78, offers his own theory on the program’s recent shortcomings in I Came As a Shadow, which was co-written with Jesse Washington of The Undefeated.

As Thompson tells it, many of Georgetown’s struggles can be traced to the modern recruiting trail. In living rooms across America, the nation’s best high school players are less likely to be captivated by the education-focused sales pitch that resonated in Thompson’s heyday. At that time, earning a degree was a common stepping stone on the path to a promising professional career; today, it can be a red flag. Many top prospects simply look for the most direct path to the NBA Draft, which is typically a single-year stint with one of the handful of elite college teams that has reoriented its program around so-called “one-and-dones.” The recruits supercharge these programs for a year, the programs provide a stage for the recruits to showcase their talents, and the Georgetowns of the world watch from the sidelines.

“Is Georgetown first and foremost an educational institution, where we care about what goes on with these kids outside the gym?” writes Thompson. “Are we truly concerned when their bodies hurt, or when they struggle in the classroom or have problems in their personal lives? Or is Georgetown more like professional sports, where winning is the only thing that matters? … I built the program to educate the kids at all costs, not to win at all costs.”

Further exacerbating this recruiting gap between Georgetown and its competitors, explains Thompson, is money. That many high-profile programs entice recruits with under-the-table offers is an open secret in college basketball, but Georgetown has by all accounts remained above the fray. By not paying up, the Hoyas have paid a price.

“If I were coaching right now, I would cheat too,” writes Thompson. “I would pay for players, because if I didn’t I would lose to the cheaters and get fired. The NCAA has almost given coaches no other choice but to cheat if they want to compete for championships.”

Collectively, these competitive disadvantages create a chasm between internal realities and external expectations. On the one hand, Georgetown staffers fight to make the best of an adverse recruiting situation, while simultaneously dealing with the typical challenges — transfers, disciplinary issues, injuries, etc. — that come with running a college basketball program. On the other hand, fans, alumni and boosters yearn for and expect a return to the glory days of old.

As Thompson writes, “Georgetown alumni, people on the board of directors, other influential members of the university community, they got used to having the Patricks [Ewing] and the Alonzos [Mourning], and living it up in New York City at the Big East tournament.”

So what will it take for the Hoyas to find their way back to the Promised Land?

Thompson doesn’t venture a guess in I Came As a Shadow, but the success of Georgetown’s Big East conference rival Villanova may offer a blueprint. Like the Hoyas, after a string of successful seasons in the 1980s, the Wildcats regressed, falling out of the upper echelons of college hoops. In the last decade, however, Villanova has rebounded, eventually winning the National Championship in both 2016 and 2018. Both title teams were powered by players that Villanova developed over multiple seasons, not a single one of whom was a “one-and-done.” Success came slowly after the hire of charismatic head coach Jay Wright in 2001, but it came, a reminder that a few diamonds in the rough can reverse a team like Georgetown’s fortunes.

A fast-approaching sea change in college basketball recruiting may offer an additional ray of hope for Georgetown fans. Colleges, it turns out, are not the only ones wary of the “one-and-done” system. Increasingly, elite hoopers are choosing to spend their mandatory post-high school year earning money and refining their talents in professional leagues. LaMelo Ball and RJ Hampton, both first round picks in the 2020 NBA Draft, spent their pre-NBA year in Australia’s NBL, while Jalen Green and Jonathan Kuminga — the first- and fourth-ranked prospects in the 2020 ESPN 100, respectively — are currently suiting up for NBA G League Ignite, a newly formed development team comprised partly of elite high school players.

“Pretty soon, very few of the best players will attend college at all,” writes Thompson. “Most of them will go straight to the NBA or the G League, or overseas, or just stay home and work out.”

That could be good news for Hoya fans. Prospects that remain interested in playing college basketball will likely resemble the recruits that John Thompson once brought to Georgetown, the overlooked players that he found “in the nooks and crannies” and built into stars. They’ll resemble the players that delivered Georgetown its first championship, and may be the players that deliver its next one.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.