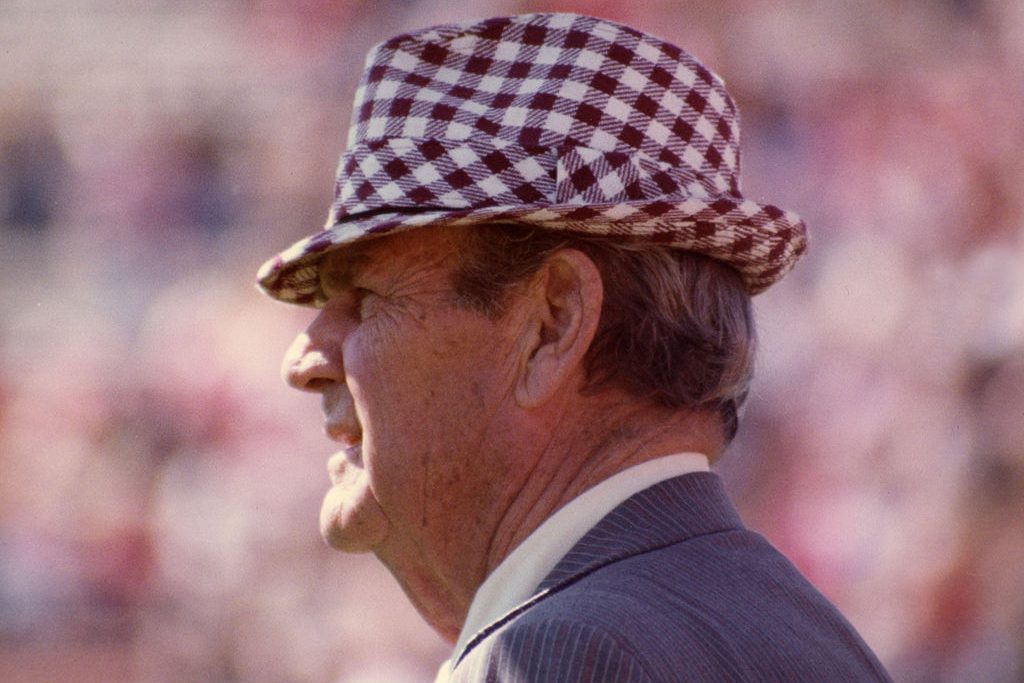

For Paul “Bear” Bryant, who won six national championships during his 25-year tenure as head coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide, football was a very simple game made up of 11 simultaneous one-on-one battles.

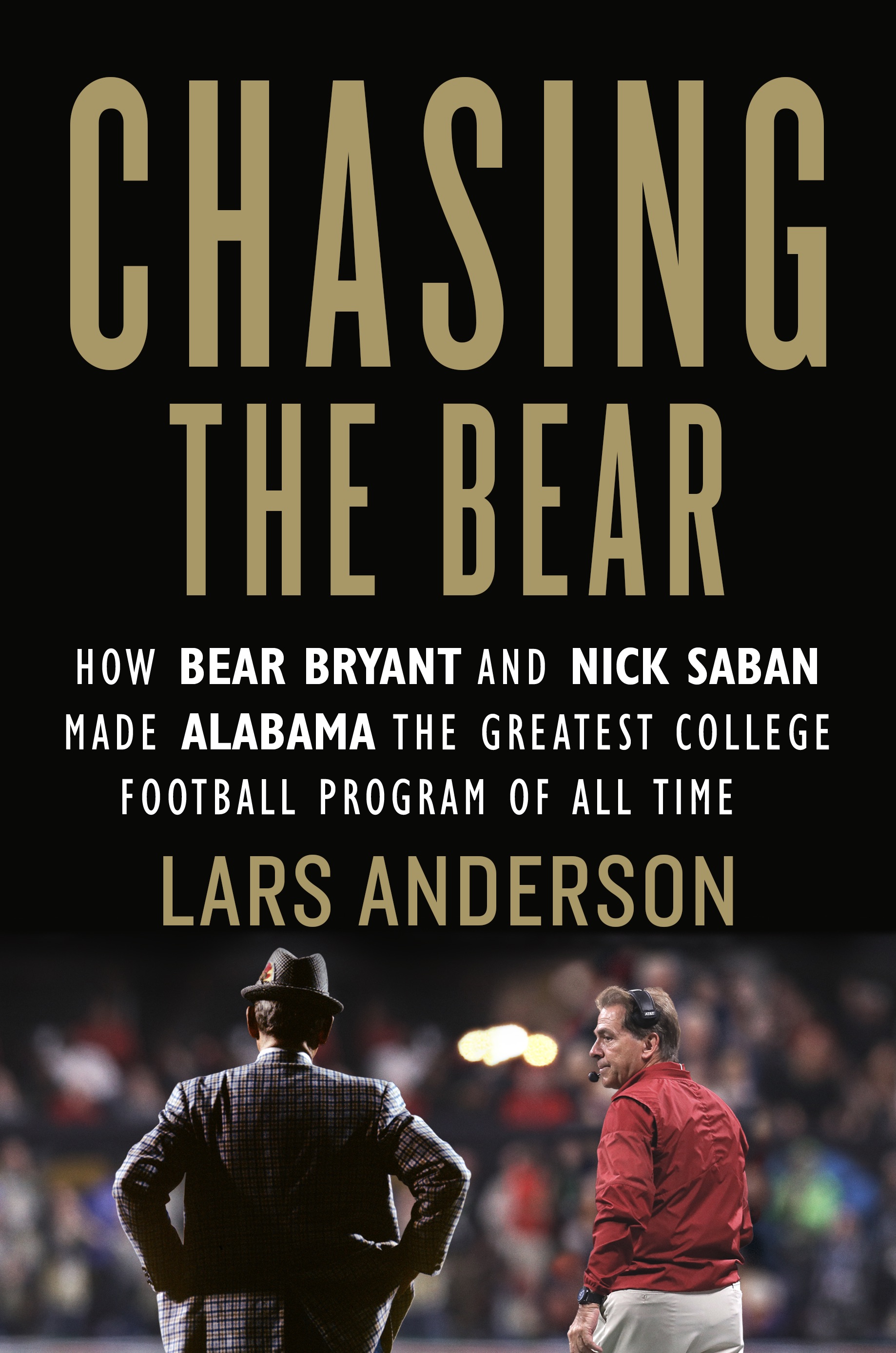

“Bryant talked about going jaw to jaw, facemask to facemask and beating the shit out of the guy in front of you,” Lars Anderson, the author of Chasing The Bear: How Bear Bryant and Nick Saban Made Alabama the Greatest College Football Program of All Time, tells InsideHook.

“He would tell his players on the opening kickoff, ‘Pick you out one of them guys and hit them right between the numbers, put them on the ground, drive them into the ground, then offer your hand to them and tell ’em you’ll be back for more. And then, do that on every single play.’ He wanted guys who would give anything to inflict pain on another player.”

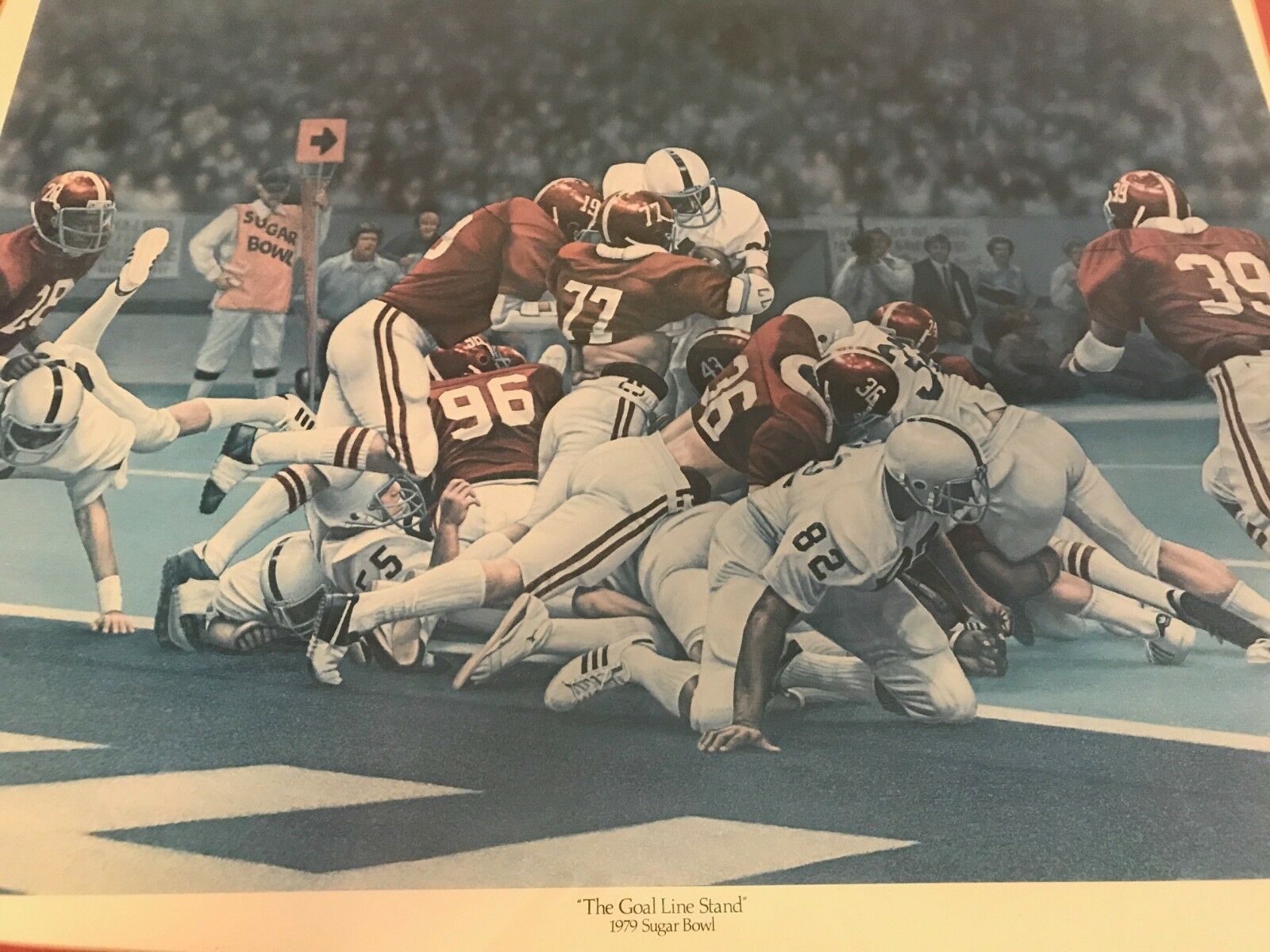

A single play which occurred during the 1979 Sugar Bowl between Alabama and Penn State encapsulated what Bryant stood for and went on to become one of the defining moments of his legendary career in Tuscaloosa.

In the following excerpt from his new book, Anderson details the goal-line play which helped cement Bryant’s legacy and would haunt Penn State coach Joe Paterno for the rest of his life because it cost him the national championship.

On the morning before the Sugar Bowl, on January 1, 1979, Bryant had his breakfast delivered to him in his suite on the top floor of a high-rise hotel that overlooked the Crescent City: an egg-and-bacon sandwich and coffee in a polystyrene cup. Bryant was thirty-six hours away from playing for his fifth national title against undefeated and top-ranked Penn State. The Tide’s only loss of the season had been to USC (24–14) in late September, and now the team was 10-1 and ranked second in the nation.

As usual before games, Bryant worried in his hotel suite— specifically about his defense. He told a reporter that the defense had played very well at times but also had struggled at various points in the season, and that this kind of inconsistency was “not recommended” when going against a team with the offensive talent of Penn State, which had won nineteen straight games.

With less than seven minutes left in the ’79 Sugar Bowl, Penn State had the ball first-and-goal at Alabama’s 8-yard line, trailing 14–7. On first down, Nittany Lion running back Mike Guman gained two yards. On second down, Penn State quarter- back Chuck Fusina completed a pass to tight end Scott Fitzkee, who was pushed out-of-bounds by cornerback Don McNeal at the one. Before third down, Alabama linebacker Barry Krauss, the defense’s captain, called the defensive play: Double-X Pinch. This sent every defender crashing into the middle to stop a run up the gut. The risky call paid off: From his linebacker spot, Rich Wingo stopped fullback Matt Suhey just short of the goal line.

Penn State then called a time-out. On the Alabama sideline, defensive coordinator Ken Donahue again called Pinch. Across the field, Penn State coach Joe Paterno wanted Fusina to fake a run and then pass the ball to his tight end in the end zone. But his assistants persuaded him to send Guman up the middle again.

In the Tide huddle, the players told each other, “This is Alabama football. This is all about what Coach Bryant has taught us.” Murray Legg yelled, “Gut check! Gut check.”

As Fusina walked to the line, defensive tackle Marty Lyons shouted at him above the din of the crowd: “You’d better pass!” The ball was snapped, and Fusina handed to Guman. Lyons penetrated into the backfield, collapsing the line, and Wingo smashed into Suhey, the lead blocker. When Guman attempted to leap over the pile, Krauss met him face mask to face mask, driving him back- ward with a hit so violent it left Krauss momentarily paralyzed. Legg, streaking in from his safety spot, then pushed Guman backward and onto the ground, six inches short of the goal line. The Tide held and won 14–7, delivering Bryant his fifth national championship.

At the precise moment that Krauss and Guman collided, SI photographer Walter Iooss Jr. snapped an iconic shot that would make the cover of that week’s issue, a picture whose spirit and upward thrust of angles faintly echoed the famous photo of the flag- raising at Iwo Jima. So powerful was the image that Daniel Moore, then a twenty-five-year-old graphic designer in Birmingham, made a painting of the scene. It’s no stretch to say that to this day Goal Line Stand is the most popular piece of artwork in Alabama; prints of it hang in countless dens, offices, restaurants, and bars throughout the state.

“That painting hit home because that single image symbolized Bear Bryant’s philosophy,” said Moore. “It was gut-check time for the players, and they made a stand.”

The play, which lasted less than three seconds from snap to whistle, has had a lasting influence on the lives of the key participants. For Krauss, who played eleven years in the NFL, it earned him a reputation for performing in the clutch. “That play got my life going in the right direction,” he said. “I’ve got that Daniel Moore painting in my den, and when I look at it I’m reminded that when our moment arrived, we made the most of it.”

The play followed Krauss for four decades, shadowing him everywhere he went, reminding him of the defining hour of his youth. At least once a week in a restaurant or grocery store or movie theater, a stranger would approach Krauss and ask him about that New Year’s night in 1979 when he made the biggest tackle of the Bear Bryant era at Alabama. “People always tell me where they were when we made the goal line stand,” said Krauss. “My favorite is the guy whose mother was in labor with him during those four plays. He told me he’s felt a special connection to me ever since, that he was always Barry Krauss when he played in backyard football games.”

For Wingo and Legg, who each have spent time working in real estate in Birmingham, the play has morphed into parable. “I ask my kids, ‘Will you be ready when your opportunity comes?’” said Legg. “Every time I see that painting, that’s what I’m reminded of.”

Said Wingo, who spent five seasons in the NFL with the Packers, “I use that play as a teaching tool all the time.”

For Lyons, who played eleven seasons with the Jets, the play represented trust and friendship. “Football is a team game,” said Lyons. “Penn State would have scored if every guy on our defense didn’t do his job. And all these years later I’m still in frequent touch with guys from that team. That play made us as close as brothers.”

And what about Guman, the running back who came up inches short? After spending nine years in the NFL with the Rams, he settled in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he and his wife raised five children. For three decades he received copies of SI with that fourth-down photo on the cover. “It’s mostly Alabama fans who want me to sign it and send it back,” said Guman. “I’m happy to do it, because that play helped mold me into who I am today. You’ve got to get up when you get down. I’ve learned that you can overcome defeat.”

From CHASING THE BEAR: How Bear Bryant and Nick Saban Made Alabama the Greatest College Football Program of All Time by Lars Anderson. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.