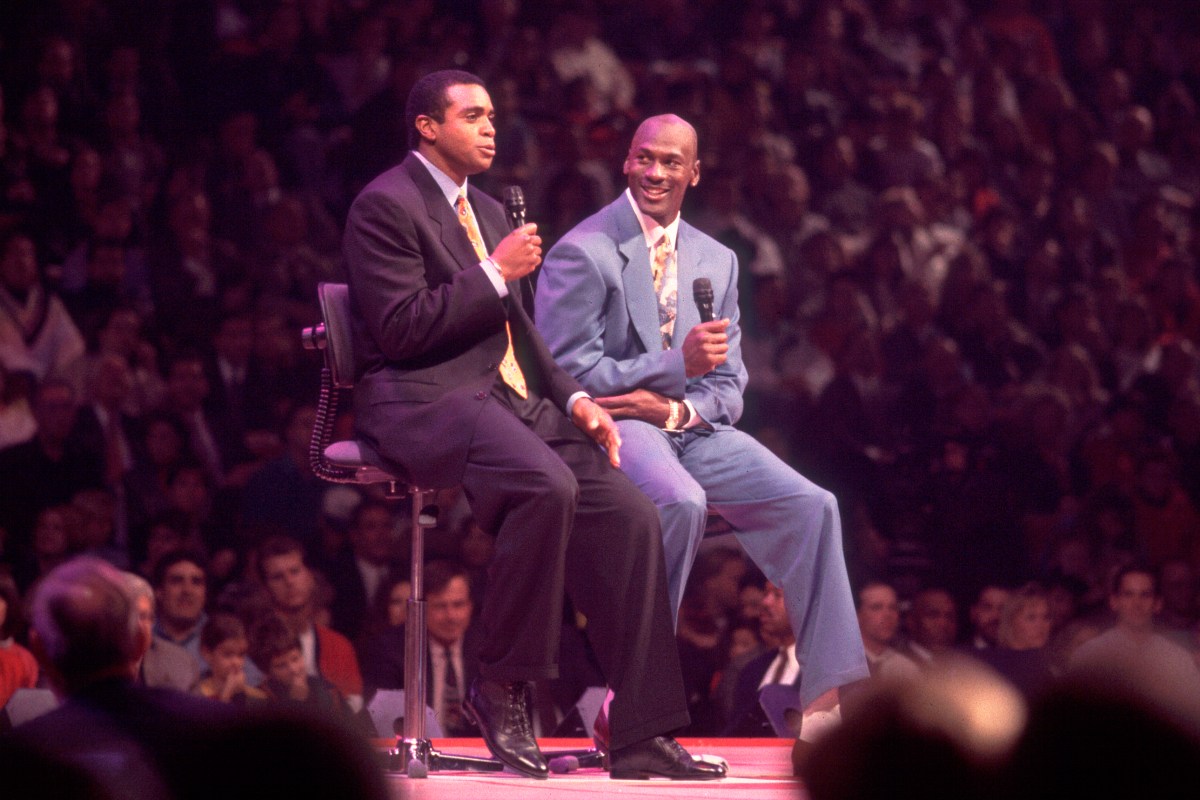

Amid the great pandemic-wrought sports drought of 2020, The Last Dance provided the world with a refresher on the supremacy of the 1990s Chicago Bulls dynasty. Along the way, we were reminded of one of the chummiest relationships between subject and journalist in NBA history — that of Michael Jordan and Ahmad Rashad.

One scene in the ESPN docuseries showed Rashad — amiable host of the much-missed Saturday morning staple NBA Inside Stuff — riding shotgun in MJ’s car on the way to a game that Rashad himself was assigned to cover as a sideline reporter for NBA on NBC. And then, of course, there was the infamous sunglasses interview before Game 1 of the 1993 NBA Finals, when Jordan, looking to break his media boycott, marshaled Rashad and NBC cameras at a moment’s notice to defend himself against rumors surrounding his gambling activities. The obvious conflict of interest was one Rashad’s bosses seemed willing to live with, if only because it gave NBC unprecedented access to Jordan’s cloistered world.

“When is the last time you and Jordan hung out?” I ask Rashad, who’s on the phone from his home in Florida.

“Hung out?” the 71-year-old says with a laugh. “He lives across the street! I just left him at the golf course.”

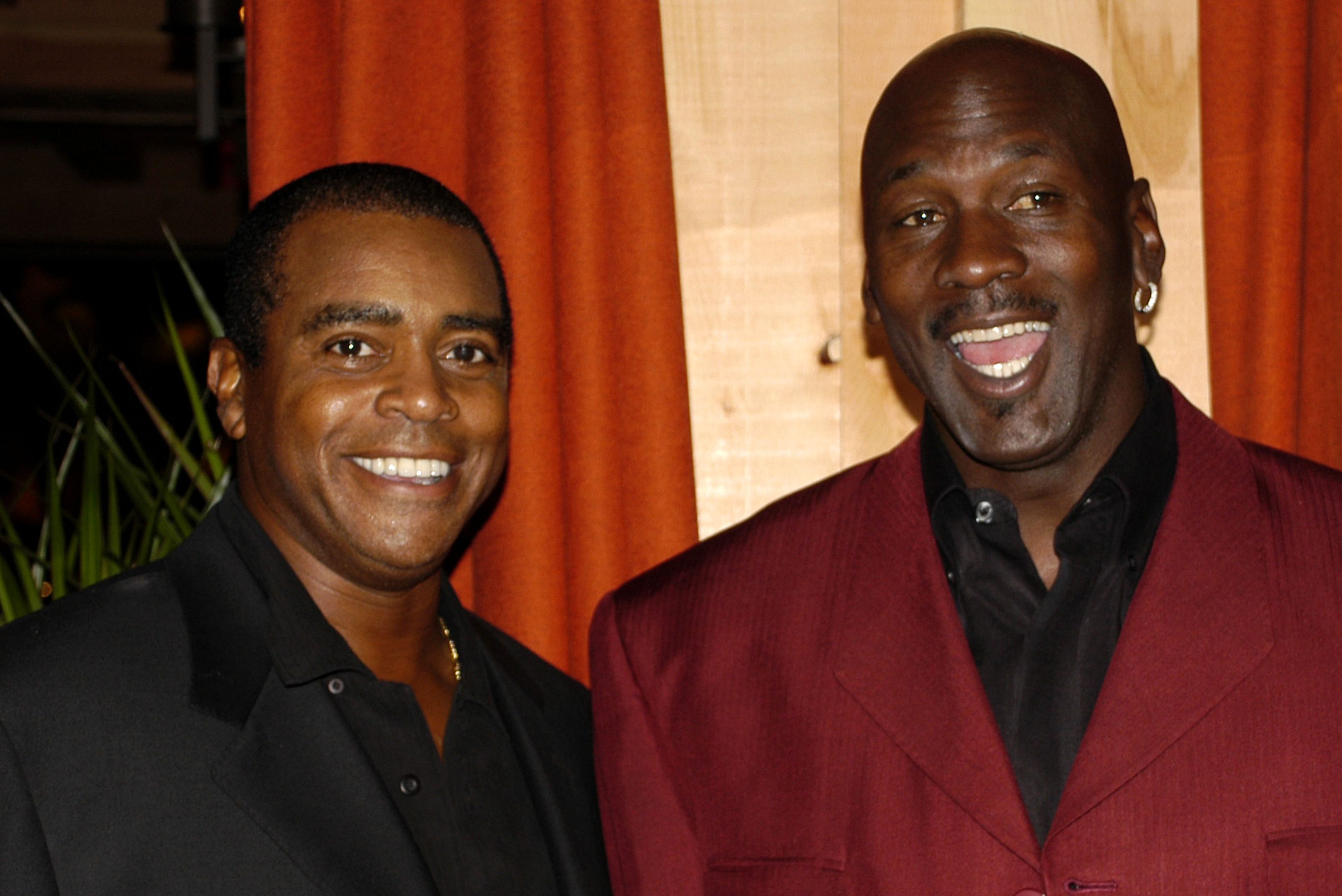

Though the broadcaster’s golfing buddy doesn’t appear on camera in Rashad’s new ESPN+ show Ahmad Inside, Jordan casts a Jumpman-shaped shadow over its five episodes, each an affectionate one-on-one interview with an NBA legend about the ’80s and ’90s — what Rashad likes to call “the day.” His sit-downs with Charles Barkley, Clyde Drexler, Patrick Ewing, Gary Payton and Pat Riley inevitably drift to talk of His Airness. So too did my interview with Rashad, in which the former NFL Pro Bowl wide receiver and pioneering Black sportscaster discussed how NBA media has changed since Inside Stuff, why basketball rivalries aren’t what they used to be and Jordan’s feelings about the GOAT debate.

InsideHook: Looking back on my 1990s childhood, I recognize Inside Stuff as the perfect product to get a generation of kids addicted to the NBA. On Saturday mornings, Garfield and Friends led into Inside Stuff. Do you hear from a lot of millennial NBA players that they grew up watching the show?

Ahmad Rashad: Not a day goes by that I don’t see somebody that tells me they grew up watching NBA Inside Stuff. Not one day goes by. At that point, it was the only inside look viewers got at the NBA. Now we have the internet, where players can go and share whatever they want to.

Right. NBA fans now get the impression of access to the players through the players’ social media accounts, through articles players publish on The Players’ Tribune and through documentaries the players themselves produce. Do you feel something gets lost when the players are putting out only what they want the public to see?

There may be something missing. Now you only get to hear what the players want you to hear. It’s not a two-way conversation. When I was doing NBA Inside Stuff and NBA on NBC, I always saw my interactions with players as a conversation. In addition to being the host of NBA Inside Stuff, I was the show’s executive producer and I always insisted the interviews be conversations — they weren’t question-answer, question-answer. That gave the audience a chance to see a player as he was when he was relaxed and having a regular conversation with me about all kinds of things — not just basketball. In that way, Inside Stuff made the viewer a fly on the wall and actually strengthened the bond between the viewer and the player. After watching Inside Stuff, you would watch a guy play and feel like you really knew him.

How exactly did Ahmad Inside come about?

It started after The Last Dance. That documentary gave you a chance to see how Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls won their championships. But during that era of the NBA, there were also a lot of other great players — guys I felt deserved to be highlighted as well. I wanted to do something that wasn’t just blowing smoke at the Bulls and Jordan but would actually help people realize how great these other players were. In one episode, Charles Barkley made a comment to me that made a lot of sense. He said the Bulls were great during that time, but they never swept anybody in the Finals. The Bulls won, but it wasn’t a walkover for them. The competition and the games were at a peak, in terms of the rivalries and the great players the league had. Look at the Dream Team. Back in 1996, the league came out with a list of the top 50 players of all time. Thirty percent of them were still playing in the 1990s. I wanted to highlight how great they were and how great their careers were.

And yet as great as they were, guys like Clyde Drexler, Patrick Ewing, Charles Barkley and Gary Payton — all of whom Jordan at one time denied championships — can’t avoid talking about playing against the Bulls.

I had a conversation with Michael about the show before I did it. I said, “I want to talk about how great these guys were. I don’t want to have these guys on to talk about how great the Bulls were or how great you were.” But it was just a natural part of the conversation that they talked about a showdown with Jordan and the Bulls in the playoffs or the Finals, and how, despite having their best team, they couldn’t get it done.

Do you think these guys get sick of talking about getting beat by Michael Jordan?

No. Because it’s about mutual respect. Michael gives respect to a guy like Patrick Ewing and Ewing respects Michael. When you look back on who Michael was playing, it makes what he and the Bulls did seem even larger — they beat these guys to win championships. Most of the guys I interview on Ahmad Inside talk about it that way. “Man, the Bulls had a great team and we thought we could beat them, but we just didn’t.” There’s mutual respect between all of the parties. The king of that era was Michael Jordan. But these other guys weren’t lackeys. Jordan’s Bulls were, at one time or another, the only thing standing in the way of other great players winning a championship.

Do you get a sense that it’s also proof time heals all wounds and that enough time has passed since they lost those big games that perhaps it’s a little easier to talk about those losses today than it would’ve been 25 years ago?

I’m sure. When I was a wide receiver for the Minnesota Vikings, I lost in Super Bowl XI. It was a crushing defeat. Now I don’t even think about it. It doesn’t even come to mind. Had we won, maybe it would’ve been in my head longer. But losing doesn’t take away the respect I have for the team that beat us, John Madden’s Raiders, or the great players that we played against. That respect will always be there. Jordan and the Bulls won all those championships, but they still respect all the players they played to get there.

Can you explain further your notion of the competition and the players being at an all-time high during the ’80s and ’90s in the NBA? There’s a lot to suggest that the average NBA player today is better than the average player 30 years ago. Players start playing basketball at a high level at a younger age. Training, conditioning and diets have improved. Offenses and defenses are more dynamic.

First of all, you can’t compare NBA eras. And the reason you can’t compare eras is that the rules have changed and the style of play has changed. In the NBA of the ’80s and ’90s, the offense was run through the center, who was positioned near the basket. Now, the center is taking 3-pointers beyond the arc. The game also used to be much more physical. Defense has changed because you can’t hand-check guys anymore. Back in the day, if you drove to the hoop against the Bad Boy Pistons, you’d find yourself on the ground. [Laughs.] Every single time, they’d knock you down. Are there some players today that could’ve played in the ’80s and ’90s era? Yes. But that era was a different kind of basketball. The other major difference is that the rivalries back in the day were able to build over many seasons. Players weren’t up and leaving their team every couple seasons to get together with their friends on another team to try to chase a championship. It wasn’t like that back in the day.

That reminds me of something Giannis Antetokounmpo said after his Milwaukee Bucks won the championship last week: “It’s easy to go somewhere and go win a championship with somebody else … I could go to a superteam and just do my part and win a championship. But this is the hard way to do it, and this is the way to do it and we did it.”

I think Giannis is exactly right. I think you earn a lot more respect winning that way. When three or four superstars demand trades and whatnot to end up on one team, they’re expected to win. They’re supposed to win.

It seemed to be a knock against the superteam concept when the Brooklyn Nets superteam — albeit diminished by injuries — lost in the playoffs.

So is the Lakers’ loss! [LeBron James and Anthony Davis] put that whole team together. There are many ways to win, but back in the day — even though there were teams stacked with talent — it wasn’t like that. You brought the guys you had to the court to try to win a championship.

As one of Michael Jordan’s closest friends, you have better insight into him than almost anyone. What is his opinion of the GOAT debate that has arisen in recent years, pitting him against LeBron? Does the fact that it’s a conversation at all piss him off? There was a sense he agreed to do The Last Dance to help refresh our collective memory of his greatness.

Here’s Michael’s answer any time this comes up: “You cannot compare eras.” You can compare stats but not the reality of the on-court style of play. And there are a lot of young people that never saw Michael Jordan play. Younger fans can talk about the players they see now and the great things that those players do, but they’ve never seen the players in the other eras in order to compare.

Does Jordan feel that if he were able to play in today’s league that he would dominate the way he did during the ’80s and ’90s?

I don’t think that kind of hypothetical goes through his mind. That’s what The Last Dance was about. It was him saying: “Look, this was it. Now you can think whatever you want.” Notice, he’s never done interviews about it after the series ended. The Last Dance was him saying, “Here it is. You can make up your own mind.” From that point on, he’s not interested in talking about it. But I’ll say this — here’s a guy who never took a game off. “Load management” was not in his vocabulary.

You and Jordan were close even as you were covering him as part of your beat for NBC during the ’90s. Was that conflict of interest ever the subject of a conversation you had with your bosses?

There was no conflict of interest. Look, we happened to have the Bulls on NBA on NBC almost every Sunday. And I had access to Michael and the Bulls and that was a big plus for the network. As much as Michael and I hung out and he would give me a ride to the game, we would hardly ever talk about basketball. But our relationship was a plus for the network. And I had relationships like that with players on all the teams.

It seems that way. In the episode of Ahmad Inside featuring Patrick Ewing, he’s recalling his battles with the media, and he says, “You and I have been great friends for a lot of years. Some guys are good guys, and some guys are assholes.” Who were the assholes in that scenario? The journalists who were less friendly than you?

I don’t know. It would be a waste of time to try to figure that out. Who cares? Patrick was a tough guy to get access to. But Patrick and I were very dear friends, so I always had access to him. I know he didn’t think I was an asshole!

Ahmad Inside is now streaming on ESPN+.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.