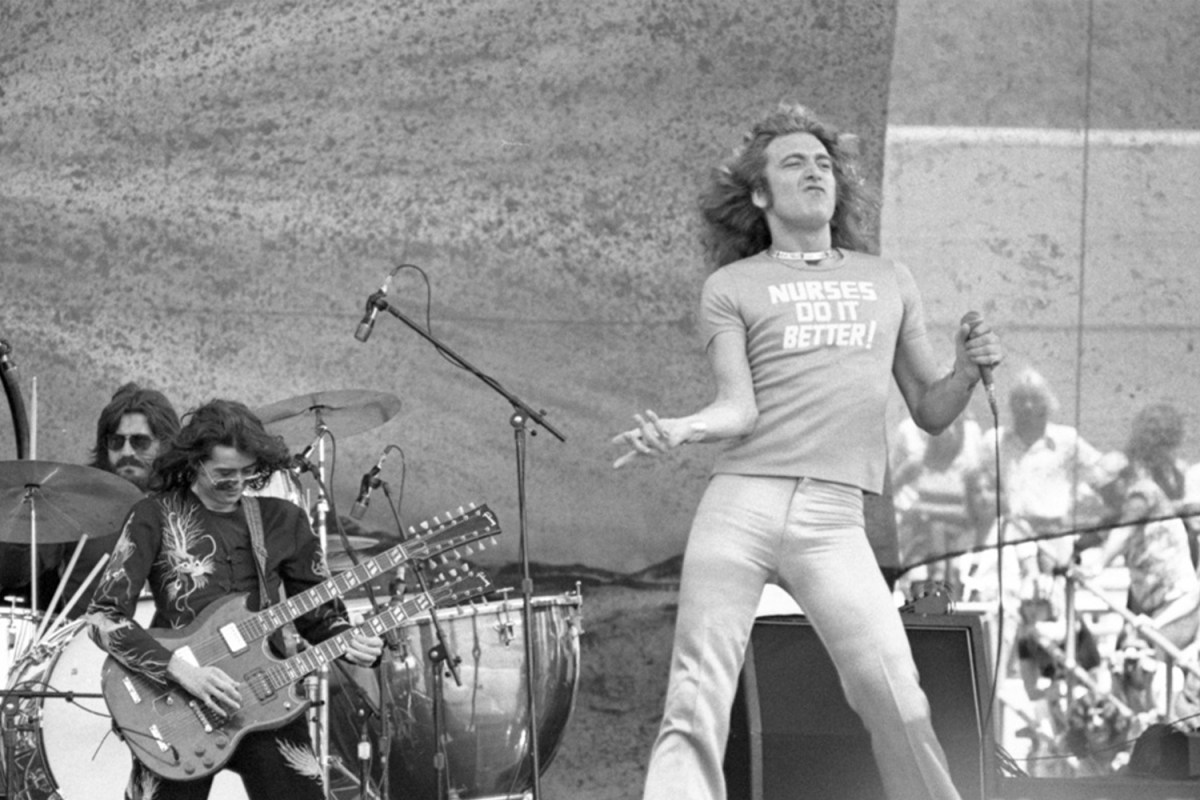

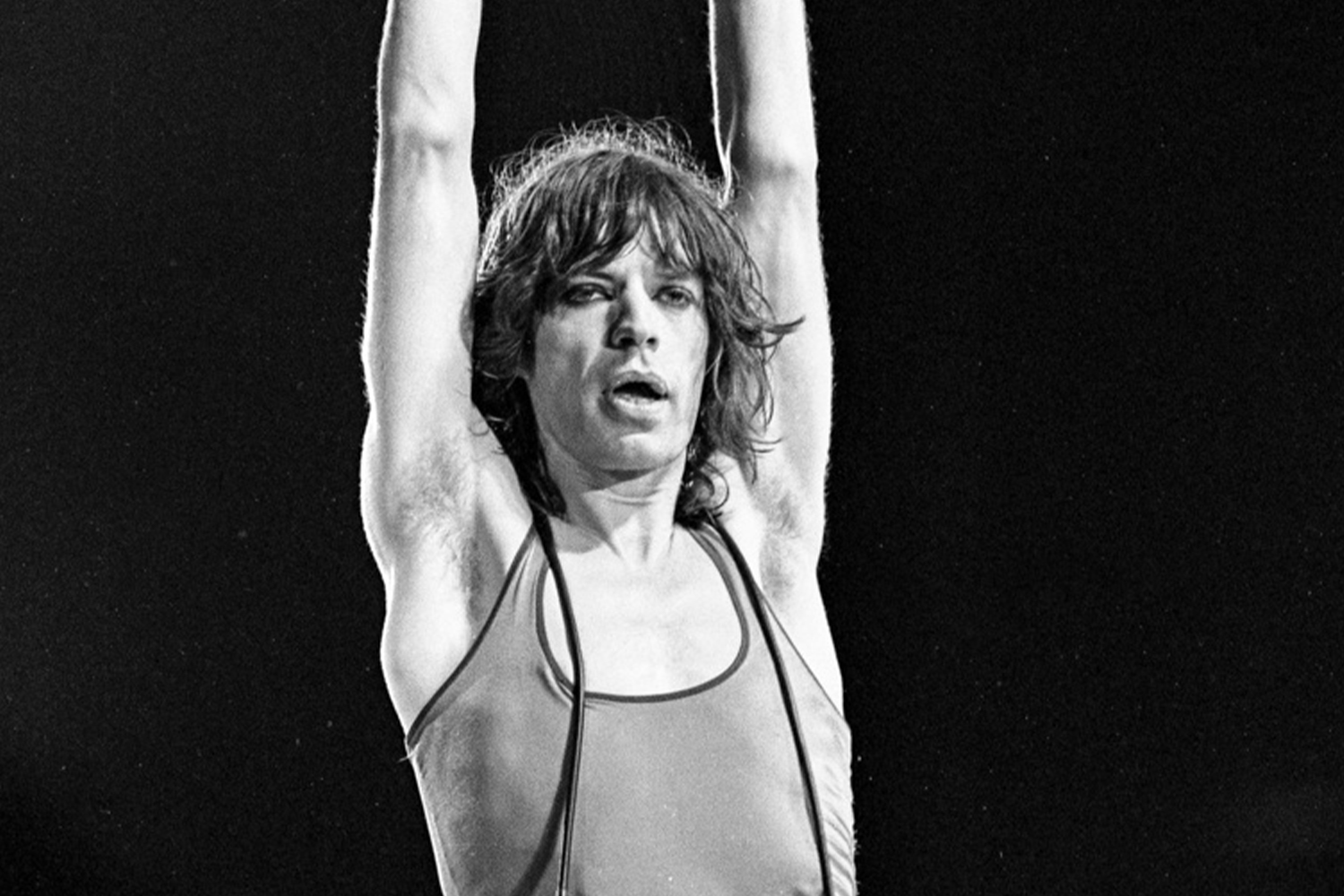

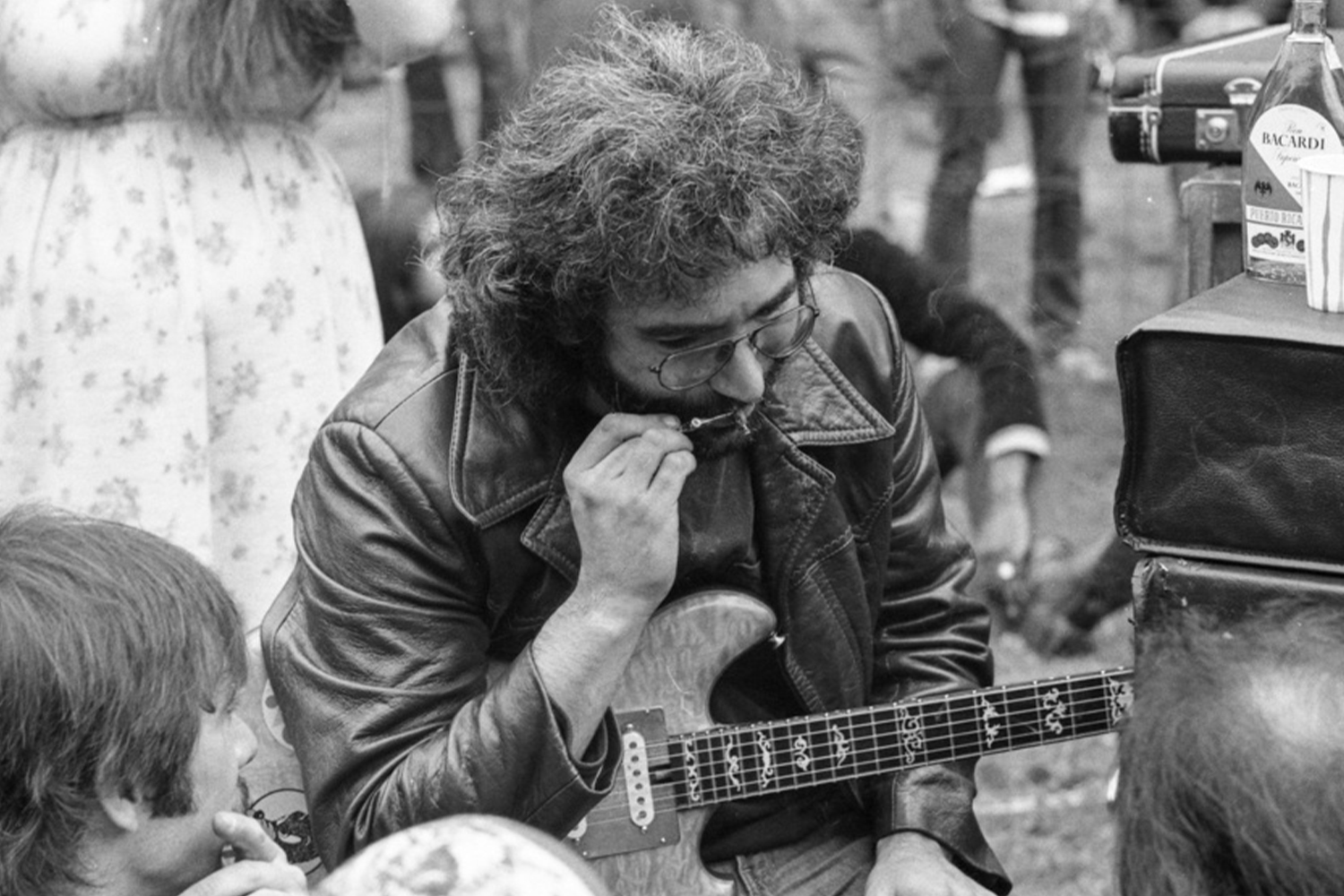

Greg Gaar’s photographs tell the story of the history of San Francisco — especially its wild, vibrant music scene between the late 1960s and the ’80s, which saw the city’s live music culture evolve in strange and revolutionary ways. Gaar’s photographs are an encyclopedic record of San Francisco’s musical story: Jerry Garcia, the Who, the Rolling Stones to Bob Dylan, the Dead Kennedys, Bad Brains and David Bowie were all among his subjects.

More than 1,000 of them, taken between 1972 and 1989, are now part of Open SF History — an already-excellent archive of the city’s photographic history. (Gaar also volunteers for the organization, which is a program offered by the Western Neighborhoods Project.) Here, we spoke to the lifelong S.F. resident about growing up in a city buffeted by change — and what it was like becoming the photographer of record for its music icons.

InsideHook: You’re a native San Franciscan. How have you seen the city change over the years?

Greg Gaar: It’s kind of hard to take, you know. I don’t even recognize downtown anymore — I used to go downtown all the time, just to walk down Market Street and go into the shops. Now so much of Lower Market has been demolished to make way for these faceless high-rise buildings.

Then there’s the lack of affordability. When I lived in the Haight-Ashbury, my rent was $50 a month. The entire flat, between myself and three roommates, was $200. We paid $50 each, and it allowed us to be artists on the side. Now, to live in San Francisco, you’ve got to be able to make hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions. It doesn’t give you the freedom that you might have if your rent was cheap, which takes away from your creativity.

Do you think it’s possible to be an artist in San Francisco right now?

I’m able to be very creative because I inherited the house I’m living in. When my parents passed away, my brother and sister wanted to sell the property that we grew up in, and I said, “No way, man. I’m bonded to this house.” Right now, I’m sitting on the front steps, looking out to San Bruno Mountain and City College. My whole garden is San Francisco native plants, which I propagated from seed. That’s my real love right now — restoring habitat. It’s the best thing you can do to repair the damage that we’ve done to the planet. Once they get established, I don’t have to water them anymore because native plants are adapted to the environmental conditions where they’re native, and then they support the native butterflies, the native birds, the native bees and native wildlife.

I feel like what you’re talking and in all these cases is the flourishing of the arts scene, the flourishing of music in San Francisco, the flourishing of its native species, and how threatened those are …

A lot of it is similar to all big cities in the world now — especially in the United States. In the 1950s, people fled to the suburbs to escape, and now they’re coming back because they don’t like to commute. When I grew up in this neighborhood in the 1960s, it was predominantly an African-American neighborhood. The wealthiest black people in San Francisco lived here, and a lot of them were very famous — Abe Woodson of the 49ers, or Calvin Simmons, who eventually became conductor of the Oakland Symphony, Carlton Goodlett— the street that City Hall is on, Goodlett Street, is named after him. It was really great to grow up in this neighborhood. We just enjoyed each other’s company.

Does the San Francisco seen in your photographs exist today? They seem to show a freedom and licentiousness and a world that might not exist here anymore.

Back then, you’d go and rap with [the bands]. The joints get passed around. I feel very privileged to be able to go back backstage and meet with Jerry Garcia — now he’s looked upon as almost a god, but not back then.

The first time I saw the Grateful Dead, they were playing in the Panhandle in January 1967. In those days I’d ride my motor scooter to get to the Haight-Ashbury — in those days, it was rough. I would ride up and over Twin Peaks, and then come down to the Haight-Ashbury on Ashbury Street. The Grateful Dead would be sitting on the front steps of 710 Ashbury, where they lived. On hot days, they would be squirting cars with a water hose as the car went by. And since I was on a motor scooter, they sprayed me with water. Back then, they were just a garage band. The scene was just very local. You’d see Janis Joplin shopping on Haight Street.

When did everything change?

The Monterey Pop Festival in June of 67 — with the documentary that was made about it, everybody was able to see how great Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin were. That’s when Jimi Hendrix became well-known, when he set his guitar on fire on stage. Monterey Pop made a lot of the local bands famous.

I feel very lucky that I was able to see the San Francisco bands and the hippie bands, the Summer of Love bands. In time, I became a fan of local punk rock bands as well, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. I was one of the older people to go to those punk shows — most of the people there were teenagers or in their early twenties.

The reason I got into punk was because I had a button machine. I’d make buttons of, like, Jerry Garcia smoking a joint, and then I’d try to sell the buttons outside of Winterland, where the Grateful Dead were. Then Bill Graham and the Grateful Dead confiscated my photos and buttons for selling outside of the concert hall. I had to go back to Winterland the next day claiming I was going to get my lawyer to get my photographs back. I didn’t even have a lawyer, but they gave me the stuff back and said, Don’t ever sell that stuff outside of the Winterland again. After that I just got disillusioned — I was a fan, and all I wanted to do was get into the concert.

As time evolved, the Grateful Dead just said, “Hey, we’ll let people sell whatever they want to sell outside of our concert.” So I was one of the early people to actually sell stuff at a show, just to get enough money so I could get inside.

What did you make of that wave of punk bands that followed the hippies?

I went to the show when the Sex Pistols came to Winterland. It seemed like Bill Graham — or as I called them, the Bill Graham goon squad — who would yell at people if they were dancing in the aisle, they didn’t know how to handle the punks because the punks looked kind of scary. The punk scene allowed people who had been wimps to appear scary. I saw the Sex Pistols with the Nuns and the Avengers. And I said, “This is what rock ‘n’ roll really should be.”

There were a lot of different punk clubs throughout San Francisco. My favorite was in the Tenderloin, called The Sound of Music — everybody called it the S&M Club.

You could go right up front and be right on the stage and take pictures right there. Some of the bands became famous, some of them didn’t — but you were right up front.

Do you have a favorite among the music photographs?

The one that I’ve printed the most is Jerry Garcia smoking a joint. He was Captain Trips, after all. When you talked to him, he was a very down-to-earth guy. We talked about how he went to Balboa High School and I went to Lowell.

One of my favorite pictures is the one of Peter Townsend leaping in the air at the concert in Oakland, on October 10th, 1976. I got him really high up in the air, and you could see the whole band.

I know you give slideshow talks on the history of San Francisco.

I do the slideshows whenever I’m asked to give them — I can’t do them online because I do them the old way, with a slide projector and 35-millimeter slides. I do slideshows on the history of Golden Gate park, the history of the Haight, the history of the Castro. the history of Mount Davidson.

How would people find out about them if they wanted to go attend one?

That’s their problem. I’m not going to advertise it. Whoever’s sponsoring the presentation, it’s up to them to do the advertising.

This article was featured in the InsideHook SF newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Bay Area.