Before the end of the Cold War, the pervasive fear of a nuclear winter clung to the zeitgeist like—well, like an ominous cloud on the horizon.

That’s because the scenario is exactly what scientists believed would happen if the U.S. and the Soviet Union hurled 100 or more nuclear weapons at each other in a war: superheated ash from the firestorms of razed cities would rise into the atmosphere and blot out the sun. The resulting chill blanketing the Earth would decimate agriculture and leave hundreds of millions to die of starvation.

But as the geopolitical landscape changed, the public has turned its attention to other, more pressing worries.

That is a mistake, says Alan Robock.

The climate scientist, using computer modeling, suggests a nuclear winter could still be very much in the forecast, and he’s been trying to galvanize government response to prepare for the possibility of one. He is among the real-life oracles profiled in the new book, Warnings: Finding Cassandras to Stop Catastrophes, which was co-authored by former White House staffers R.P. Eddy and Richard Clarke.

“As the Soviet-U.S. tensions have resolved and it’s less likely for us to throw nuclear weapons at each other … people kind of forgot about the threat of nuclear winter,” Eddy told RealClearLife.

“What (Robock) is saying is, sure if the U.S. and Russia threw a hundred nuclear weapons at each other we’d have a nuclear winter, but we could have a nuclear winter if India and Pakistan throw five nuclear weapons at each other,” Eddy continued. “Extrapolating even further, we could have a catastrophic nuclear winter if North Korea and the United States throw a bunch of nuclear weapons into the Korean Peninsula.”

He added: “Here is a data-driven expert making a warning that’s very, very important to look at. So if I was back in the White House now talking with the president as I did with previous presidents about [the possibility of using] nuclear weapons against North Korea … I’d say, ‘Mr. President we’d better figure out Robock’s concern of us setting off a five-year nuclear winter that could kill millions of people.”

“Cassandras”—named after the doomed oracle from Greek mythology whose visions were ignored—are whistleblowers and farsighted experts who sound the alarm for potential threats before they happen. One recent example is Richard Ford, the former U.S. ambassador to Syria, who warned the Obama administration in early 2011 that the Syrian civil war was leaving a vacuum near the Iraqi border that would be filled by a terrorist group if the U.S. didn’t act. We didn’t, and ISIS emerged in that region exactly as Ford predicted.

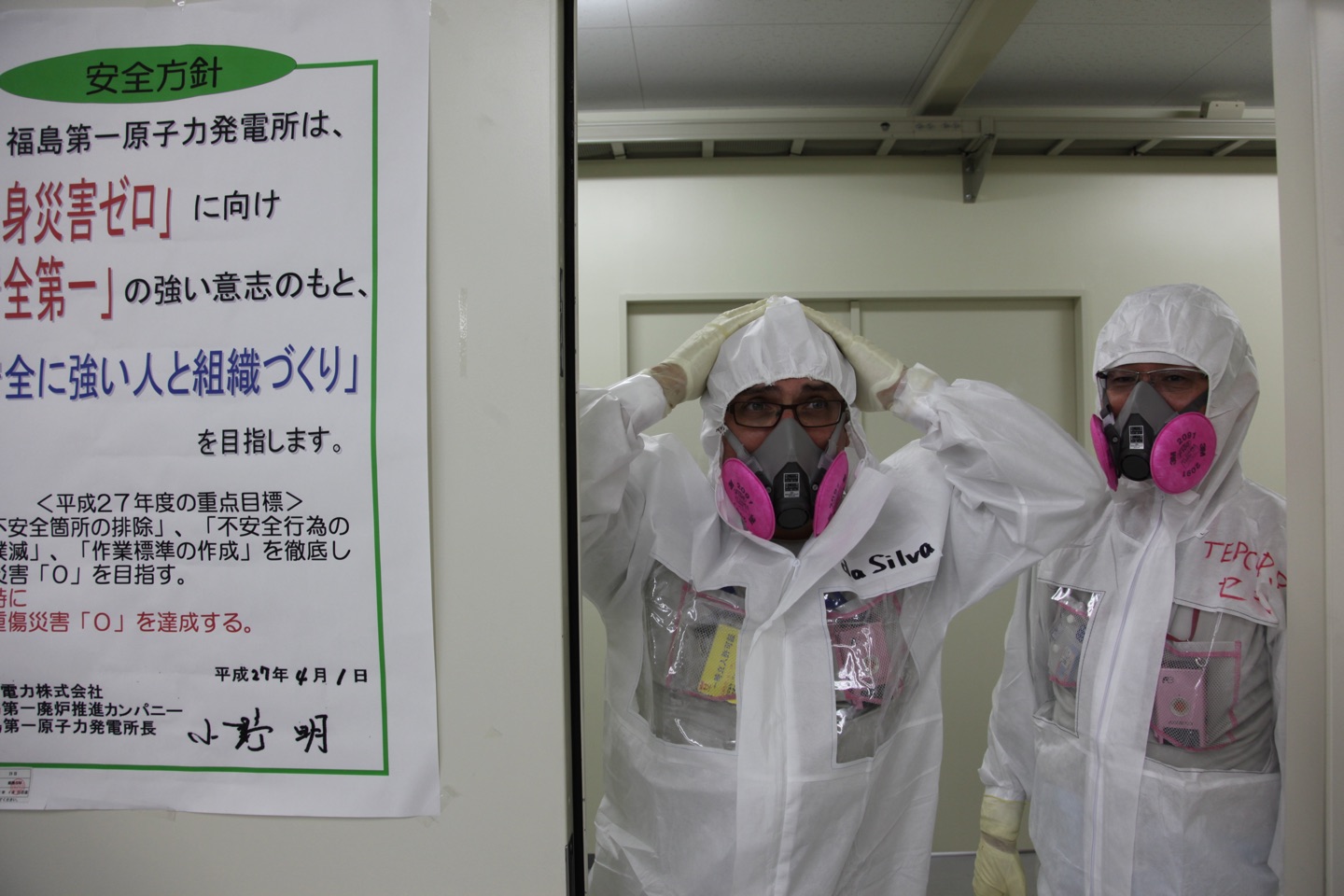

Another is seismologist Yukinobu Okamura, who tried to warn Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency that the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was not properly fortified for a potential earthquake-caused tsunami. He was ignored—until he was proven right two years later, on March 11, 2011.

“That one disaster, that one Cassandra, that one catastrophe to me is the most glaring example of getting it wrong,” said Eddy, who writes the Flashpoints column for RealClearLife. “Of someone being so clear in their warning, but the powers that be just getting it wrong.

The book is a sobering and deeply-researched look at crises just over the horizon that is an essential addition to everyone’s bookshelf.

Both Eddy and Clarke served in national security roles in the White House and now run private consulting firms that help protect corporations from impending threats—the former with Ergo, the world’s leading intelligence firm. Plenty of potential warnings crossed their desks, though it wasn’t always clear which ones to heed.

Clarke, former counterterrorism chief under two administrations, is himself a noted Cassandra, having tried to warn President Bush’s inner circle about the looming threat from Al-Qaeda in the months leading up to the 9/11 attacks.

“It’s hard to separate the wheat from the chaff,” said Eddy. “Don’t dismiss that person so quickly. If one manager, if one police chief, if one mayor, if one person in the White House gets that right, great.”

From his time as a director of the National Security Council in the late ’90s, Eddy remembers vividly being approached by a potential Cassandra—with some of the details being left classified.

“I was in a foreign country sitting at a bar trying to go home and this guy comes up to me and pitches me for asylum, saying (he is) a biological weapons scientist at a country that we care about and they are working on some really scary stuff that (the U.S.) needs to hear about,” recalled Eddy. “The details that he was able to say, and the way he described it, made it very clear that he was super credible.

“…We had a conversation with the folks in the U.S. government who study this stuff and at that point they said, ‘It’s not true, what (the asylum-seeker) is saying we are doing; science doesn’t allow for it yet.’

“But now those threats that were not scientifically possible in the late ’90s are possible now.”

There is plenty that still keeps Eddy up at night—particularly the eventual prospect of an artificially intelligent computer achieving “super intelligence” and not calculating an efficient purpose for humanity. (It’s not just a scenario out of The Terminator; major experts from Elon Musk to Stephen Hawking and Bill Gates have been sounding the alarm.)

Despite the serious message, however, Eddy insists he and his co-author wrote Warnings with an optimistic message for readers.

“You write these (chapters), one after the other, about the most horrific events that happened to humanity,” said Eddy. “Those things happen. But the point of the book is if you look at (them), there’s actually something extraordinary that we discovered here. We’ve had catastrophes and we’re going to continue to have catastrophes, but if we look at a whole number of them, we could have mitigated or stopped some of them….”

To that end Eddy and Clarke have partnered with several other notables to launch an annual Cassandra Award to help publicize the next generation of predictors and maybe mitigate or stop a future catastrophe. Offering a prize of at least $10,000 for the first such award, they’re asking the public to help nominate potential Cassandras through the site, FindCassandra.com.

“Here’s a framework to find the person you need to listen to more,” Eddy added. “Just imagine if we can mitigate or prevent one disaster because one person asked one more question.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.