“People see graffiti as a symbolic assault on them,” a psychologist told The New York Times in 1980. “They feel frightened, violated.” When Martha Cooper was photographing subway graffiti in New York, the words “plague” and “epidemic” were also used to describe the images spraypainted across the transit system. But she remained intrigued by the form, spending years getting to know its participants and chronicling the world they created with just a can of paint

“In the ’80s people thought I was wasting time shooting graffiti. It was nearly impossible to get the photos published,” Cooper tells InsideHook.

While graffiti was once considered a symptom of urban blight, it’s now regarded as an artform by mainstream culture. It’s celebrated and permanently embedded in our modern visual vocabulary, even though those involved back in the day always knew its value. As the thinking about graffiti’s value changed in mass audiences, so too did the larger photography world’s relationship to Cooper’s images. “Now I am inundated with requests for those photos,” she says.

We spoke in the weeks after a screening of Selina Miles’s new documentary Martha: A Picture Story at Fotografiska New York. Martha: A Picture Story chronicles Cooper’s journey through photography. She grew up surrounded by cameras, spent time documenting subcultures in Japan and worked as a staff photographer for the New York Post before her subway graffiti years, a pursuit that remains alive and well today.

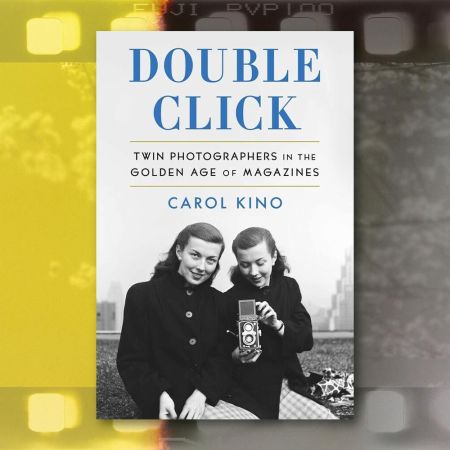

As Cooper mentioned, there were very few outlets willing to publish images of or related to graffiti when she first started taking them in the 1970s. In 1984, she and colleague Henry Chalfant released their book Subway Art, chronicling both the graffiti of the time and its people. Cooper had left her job at the Post specifically to spend more time making images of graffiti and b-boying, but before long was having trouble making ends meet. She had high hopes for the book.

“My hopes for Subway Art were twofold: 1) People would understand the phenomenon and appreciate graffiti as a legitimate art form invented by youths. 2) That photo editors would appreciate my photos and give me assignments,” she says.

And while the book now is considered a monument to the work of that era, at the time it mostly languished on shelves (or was stolen from them). Neither of Cooper’s wishes were realized after the book’s publication — not directly after, anyway. “I kept going because I wanted to follow the culture and see where it was going and because I couldn’t think of any better alternatives,” she says.

Her instinct to stick with the subject was right. Subway Art is now regularly referred to as a graffiti bible. It was the first exposure many artists had to the form that now affords full-blown careers to OGs like Seen and has made household names of Shepard Fairey and Banksy, among countless others. “Subway Art is one of the main reasons graffiti became a global phenomenon,” Fairey said upon the book’s 25th anniversary in 2009. “For everyone that didn’t grow up in New York City and even those that did, Subway Art became their main source of inspiration.” Cooper has become a celebrity of sorts to those who know the book — a scene from Martha: A Picture Story shows her signing autographs and taking pictures with fans, somewhat overwhelmed by it all and wishing she could leave to take more pictures.

But perhaps there’s a better word than celebrity for Martha Cooper’s impact on those who adore her work. “Street art is not subculture now. It’s become as widely acceptable as the walls of Wynwood,” says Wendi Weinman, Director of Programming of Fotografiska New York, referencing the chic, graffiti-laden Miami neighborhood. “I think that’s why she’s celebrated, because she’s a pioneer in that space.”

Cooper’s images are classic photojournalism, straightforwardly capturing the moment at hand. As such, they became an invaluable chronicle of an artform in an era where few in mainstream culture understood it. This is part of Cooper’s goal for her work. “I like literal documentation of everyday life. I often feel that photographers are trying too hard to capture dramatic moments or shoot from unusual angles or under special lighting conditions. The photos become more about the person taking them than about the subject matter in them,” she says. “My photos look ordinary in comparison but my hope is that in the future, the pictures will become historic documents of a time and a place.”

Graffiti wasn’t ever Cooper’s sole interest, though. Throughout her career, she’s shot a host of subcultures she has since been able to share with the public through several other book publications. “My broader interest was in photographing art in people’s lives outside galleries and museums. For example, I shot interesting hairstyles, customized clothing and handpainted signs. I’m always on the lookout for people creating art in their everyday lives. This turns my everyday life into a fun treasure hunt,” she says. Many of her books after Subway Art were first published in the mid-2000s, almost one a year for several years, as the popularity of her work surged. In recent years, Cooper’s work has also shown in galleries and museums around the world.

And at 79, Cooper is still going, and little in her work has changed: the documentary features her following a group of European taggers on their evening’s exploits. Her trustworthiness is well-established through decades of image-making and her subjects are always human, never othered by her lens. These are facts insiders today recognize as they invite her on escapades to document their work. Despite decades of silence, Cooper’s work has proven itself not just essential, but beloved.

“I pretty much shoot the same way I always have,” Cooper says, “Though perhaps with a little more confidence that I’m not wasting my time.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.