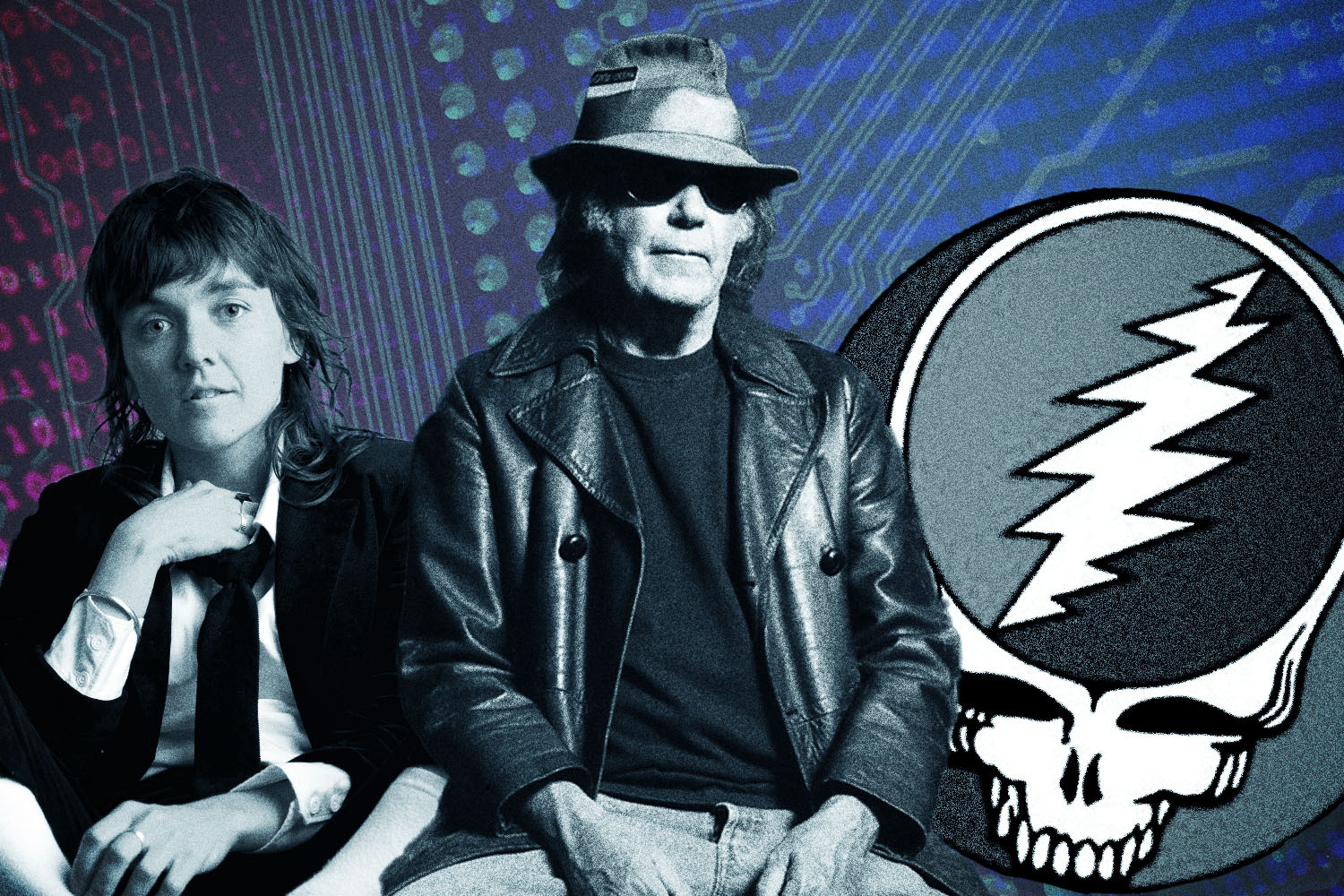

When St. Vincent first announced her new album Daddy’s Home (out now via Loma Vista) back in March, she also unleashed a new ’70s-inspired persona, complete with a Candy Darling-inspired blonde wig, a trio of soulful backup singers and retro stage costumes that included a wide-lapel jacket with the word “Daddy” embroidered on the back. It was a big shift both sonically and aesthetically for the artist also known as Annie Clark after her 2019 record MASSEDUCTION (which was all futuristic neon colors, geometric shapes and robotic movements), and as the press materials noted, it was inspired by her father’s release from prison.

“She began writing the songs that would become Daddy’s Home, closing the loop on a journey that began with his incarceration in 2010, and ultimately led her back to the vinyl her dad had introduced her to during her childhood,” they read. “The records she has probably listened to more than any other music in her entire life. Music made in sepia-toned downtown New York from 1971-1975.”

Then came the backlash. The gritty, streetwise ’70s vibe she was going for didn’t quite jibe with the fact that her father, a former stockbroker, was in jail for white-collar crimes — specifically a $43 million “pump and dump” stock manipulation scheme. Perhaps that’s why Clark was hesitant to talk at any real length about her dad’s stint in jail or answer questions about criminal justice reform when pressed by UK music journalist Emma Madden. In a since-deleted post on her personal website titled “St. Vincent Told Me to Kill This Interview,” Madden described how the unnamed publication she was writing for killed her Q&A with Clark after her publicist demanded it be pulled on the grounds that “she found the interview aggressive.” Naturally, it raised all sorts of questions about how much control over their own narrative on any given album cycle an artist should have and what sort of personal questions are fair game in an interview. (If Clark didn’t want to talk about her father and prison, she shouldn’t have mentioned him in the press release for her album, and she always had the option to simply not do any press for the new record if she didn’t feel comfortable talking to reporters about it.) It was a bad look, and it could have easily been avoided.

Listening to Daddy’s Home, there are vague allusions to the impact that her complex relationship with her dad has had on her (as on “My Baby Wants a Baby,” where she addresses her hesitancy to have kids, singing, “What in the world would my baby say, ‘I got your eyes and your mistakes’?/Then I couldn’t stay in bed all day/I couldn’t leave like my daddy”). But she really only gets explicit about her father’s incarceration on the title track: “I signed autographs in the visitation room,” she recalls, “Waiting for you the last time, inmate 502.” The rest of the record by and large focuses on the ’70s touchstones — funky grooves, some sleepy psychedelia, a touch of sitar here and there.

Up to this point, St. Vincent has largely avoided getting personal in her music; there’s a cool detachment that allows her to shapeshift a bit with every release. Daddy’s Home is confounding because while it’s her most intimate record to date, it barely lets us in on any personal details at all. One has to wonder how this record would have been received if she didn’t mention her dad at all; it seems odd to center an entire press cycle around a person whose presence is barely felt on the majority of the album. Instead, she gets too hung up on the ’70s vibes, and much of the record veers into pastiche. It drags a little too much at certain points, and three “Humming Interlude”s peppered in throughout the record don’t help there. Lyrics like “Like the heroines of Cassavetes, I’m under the influence daily” on “The Laughing Man” feel a little too on-the-nose, and overall it feels as though Clark overcommitted to a concept that could have been used more sparingly.

Still, Daddy’s Home has its moments, and there are hints of how good it could have been had she stayed a little truer to herself musically. Album highlight “Down” perfectly toes the line between ’70s homage and modern sounds (it would fit right in on MASSEDUCTION), and the uptempo track really underscores how sleepy the first half of the album is. That and the Bowie-esque album opener “Pay Your Way In Pain” provide glimpses of what might have been, along with the sparse “…At the Holiday Party.” The album almost feels hindered by the narrative, concepts and costumes; maybe St. Vincent should have left her daddy out of it and leaned in to what she does best.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.