As more and more of rock’s greatest records turn 50, it has become almost customary to celebrate their legacies with massive, ultra-deluxe box sets full of the kind of stuff diehards love to dig into: alternate takes, live versions, remixes and rarities, tracks that were left on the cutting room floor for decades.

In that regard, the recently released reissue of The Band’s classic third album, Stage Fright, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1970 record (which was actually last August) is exactly what you’d expect it to be. There’s a new stereo remix of the album by Bob Clearmountain; a late-night hotel jam session from 1970 between Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel; a 1971 live set recorded at the Royal Albert Hall; and alternate versions of “Strawberry Wine” and “Sleeping.” But there’s one jarring change to the record’s original 10 tracks: Robertson has altered the album’s sequencing in an attempt to undo what he views to be a mistake — opening with “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” and bumping “Strawberry Wine” all the way down to track nine; moving “The Shape I’m In,” “Daniel and the Sacred Harp,” “Stage Fright” and “The Rumor” up to side one; and making “Sleeping” the closing track.

Stage Fright was recorded during a famously fraught period for the group, marred by in-fighting and heavy drug use, and in a recent interview, Robertson told Rolling Stone that he felt pressured by his bandmates at the time to bump the tracks that he had co-written with them (“Strawberry Wine,” co-written with Helm, as well as “Sleeping” and “Just Another Whistle Stop,” which were penned with Manuel) higher up in the tracklisting. “The guys were like, ‘Man, you know, some of the songs you were really pushing us for our part, they’re buried in the sequence,’” he said. “So I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to push all of that way up front.’ And it was a mistake. We weren’t falling apart, but we were wrangling and we never had to wrangle before.”

“This sequence is the story of Stage Fright,” he continued. “This is what it was supposed to be. I got thrown off track because it was a particular period with the guys. And I lived with that. It was stuck inside me.”

Of course, if Helm, Danko and Manuel were still around to see this reissue, they might beg to differ. (Garth Hudson, the only other surviving member of The Band, has remained largely out of the public eye in recent years.) Robertson is notorious for being controlling and a bit of a spotlight-hog, and Helm described “issues of artistic control” during the Stage Fright era in his 1993 memoir This Wheel’s On Fire, including disputes with Robertson over songwriting credits (“Who wanted to pour out their souls and not get credit?” he wrote) and noting that “Robbie took most of the credits, played a lot of guitar, and generally tried to assume full control of that part of the whole process” on the album, resulting in “a dark album, and an accurate reflection of our group’s collective psychic weather.”

Fifty years later, he’s still trying to assume control, erasing the compromises he made with his bandmates to make the album closer to his original vision. He insists that in later years, they admitted he was right about the sequencing, telling Rolling Stone, “After the album came out and some time passed by, everybody said, ‘You know, we should have gone with the original sequence,’ and they were kind of apologetic about pushing me in this direction. If the other guys were alive, they would love this. They would be so happy that we were able to actually do that. Everybody acknowledged that, you know, we got off the track.” Yet it’s curious that he’s waited until they’re all dead and can’t speak for themselves to make this revelation.

The thing is, try as he might, there’s no changing Stage Fright at this point. Fans who have spent half a century listening to it aren’t going to suddenly accept as canon a new track sequence that alters its narrative, and those who are younger and just discovering it for the first time simply don’t listen to music in a way where sequencing carries the same weight it did 50 years ago. If you’ve spent your whole life skipping through Spotify playlists instead of lovingly flipping a record over from Side A to Side B, you’re not really going to care where “The Shape I’m In” lands in the order. Robertson can tinker with it all he wants, but Stage Fright has already been out in the world with its original sequence for five decades; to try to change it this late in the game feels impossible and, frankly, petty.

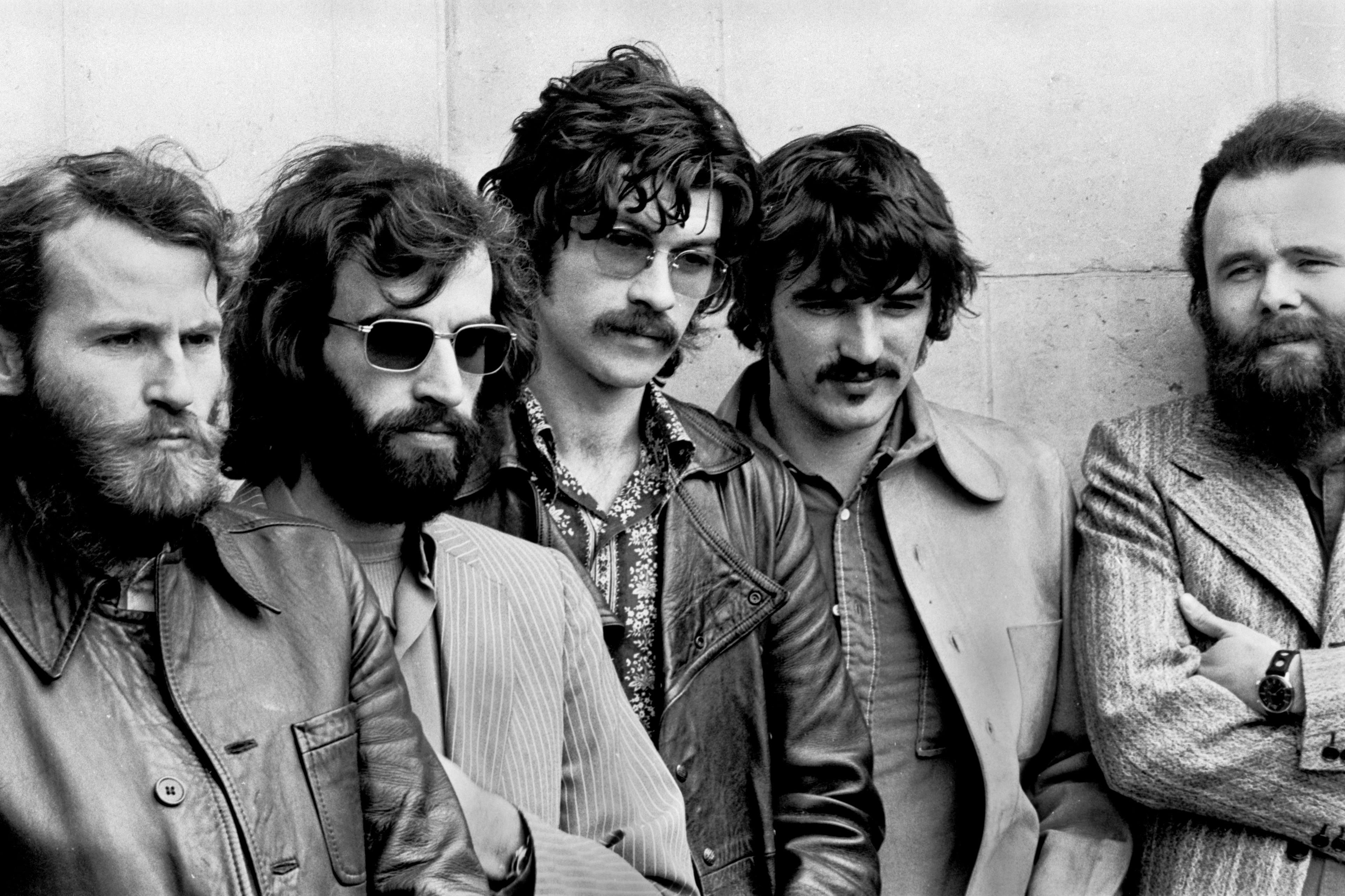

To try to rewrite history and revise Stage Fright is especially egregious because it stands as an important and compelling document of a very specific period in The Band’s career. Though it was released six years before The Last Waltz, in many ways, it signaled the beginning of the end for them as turmoil crept in and substance abuse started to get out of hand. It came on the heels of two absolute masterpieces — Music from Big Pink and The Band — and though Stage Fright is still no slouch, it was markedly different. It was darker thematically (“The Shape I’m In” was written by Robertson about Manuel’s rapidly spiraling alcohol and drug use, and he recently told Rolling Stone that “Sleeping” is “a private message to myself that there was heroin in the house.”), and the iconic three-part harmonies The Band relied heavily on for its first two records are, for the most part, gone. You can hear the fractured relationships between bandmates, and the hugely talented Manuel, much of more of a presence on earlier material but already in decline at that point, only sings lead on three tracks. The album marks a significant (albeit sad) shift for the band, and to try to improve it after the fact feels a bit revisionist.

But even with all the tumultuous drama going on behind-the-scenes, Stage Fright is ultimately a triumph. Despite everything, it’s still a damn great record, and it serves as a reminder of just how massively gifted The Band was. Even when they were falling apart at the seams, they were able to keep it together long enough to record an album that’s still better than most bands’ best, one so beloved that we’re still talking about it and revisiting it 50 years after the fact. It’s remarkable, warts and all. Why would anyone want to mess with that?

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.