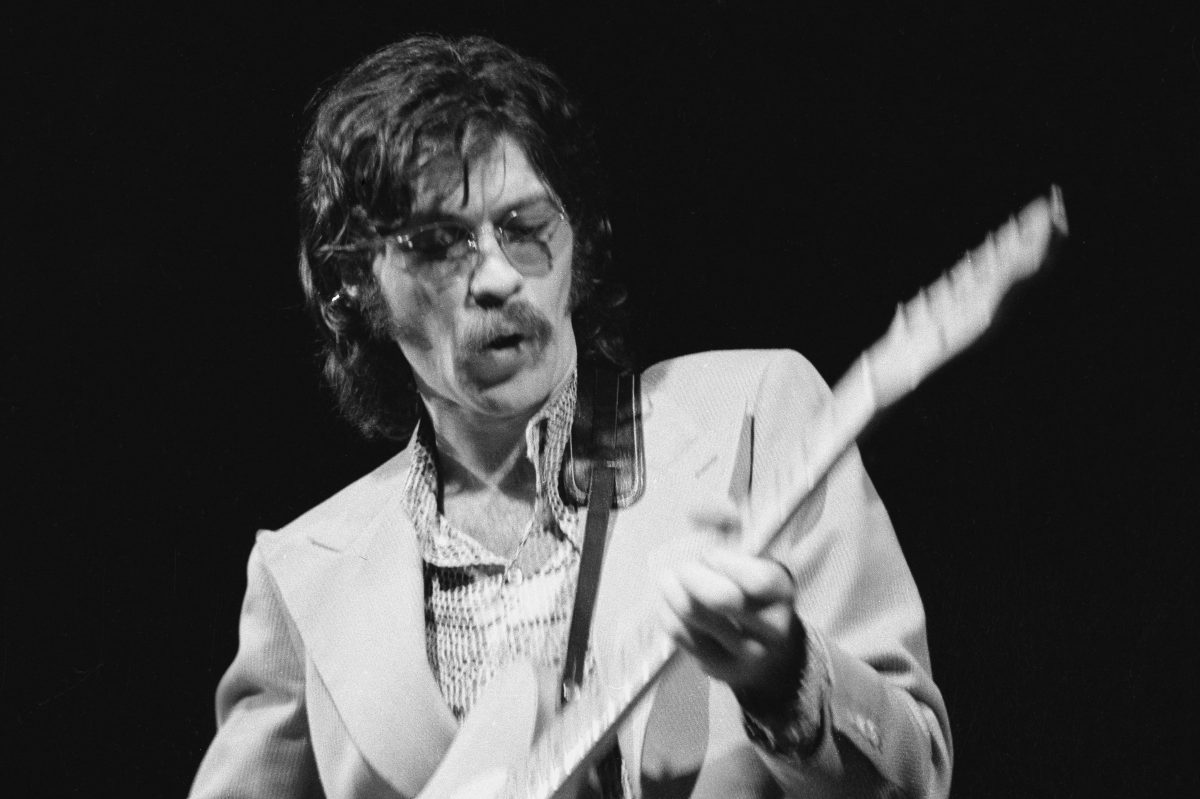

It was nudging past the 15-minute mark of an allotted 20-minute interview, my first with The Band’s Robbie Robertson, who was promoting his then-new memoir, Testimony, and Robertson had barely paused after some brief hellos and my first question about the intricately detailed childhood memories of hearing the stories of the Peacemaker, an elder on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve, in Canada, recounted in the book. Given that he was a born storyteller and, after all, Robbie Robertson, I didn’t want to interrupt. Besides, I was transfixed. Robertson set the scene, recounted the players, recalled being wide-eyed as a child seeing the elder as larger than life.

But the clock was ticking, after all. I tried in vain to get the conversation back on track. Robertson was having none of it. He continued on, well past the 20-minute mark, when, finally, he paused.

“I became aware that I had a gift, too,” Robertson said, winding up his story. “I had a special gift, and at some time I would find a way to use it.”

Gingerly, I reminded Robertson that our allotted time had long since passed, but that I really hadn’t gotten what I needed to help tell the story of how his memoir came to pass. “No problem,” he said, obligingly. “Let’s get started.”

Several hours and a change of batteries in my creaky, old recorder later, we wrapped.

“I can’t wait to do this again,” Robertson said, and, unlike so many interviewees, he seemed to actually mean it. I couldn’t either.

Over the next few years, I interviewed Robertson numerous times — about his days backing Bob Dylan with The Hawks (later, of course, The Band) and recording with Dylan in the basement of Big Pink, The Band’s homebase in West Saugerties, New York; about making The Band’s debut album, the genre-defying Music From Big Pink, as well as their magnificent sophomore effort, known as the “Brown Album,” and the later, but equally charming Stage Fright, as well as his 2019 Band documentary Once Were Brothers. We ran into each other socially, making plans to visit Tulsa’s Bob Dylan Center, with him telling me about his latest solo recordings, the status of the second volume of his memoir and his newest project with his longtime friend and collaborator, the director Martin Scorsese.

Each time, he was warm and always happy to share an amazing anecdote that I — a lifelong fan of both his work with The Band and his excellent solo albums — had never heard before. Most were on the record; some were not. They all deserved to be heard, and I felt lucky to be on the receiving end each time.

Robbie Robertson, Co-Founder of The Band, Dead at 80

The legendary songwriter died Wednesday after “a long illness”And so, it was heartbreaking to learn yesterday that Robertson had died at 80. His longtime manager Jared Levine shared the sad news with the world.

“Robbie was surrounded by his family at the time of his death, including his wife, Janet, his ex-wife, Dominique, her partner Nicholas, and his children Alexandra, Sebastian, Delphine, and Delphine’s partner Kenny,” Levine said in a statement. Fittingly, Levine added that, “In lieu of flowers, the family has asked that donations be made to the Six Nations of the Grand River to support the building of their new cultural center.”

“My heart breaks for the family of Robbie Robertson, and I think it’s safe to say that without his influence the music we love and the music we make would be very different from what it is,” wrote musician Jason Isbell on Twitter.

Of all the tributes, that one struck me as the truest, because Robbie Robertson and his bandmates in The Band made music that defied both genre and popular trends. In fact, while The Band’s music was made in the 1960s and 1970s, it could have just as easily been conceived in the 1860s and ’70s — or in the future, for that matter.

“I wanted to write music that felt like it could’ve been written 50 years ago, tomorrow, yesterday — that had this lost-in-time quality,” Robertson said in the 1996 PBS documentary Shakespeares in the Alley.

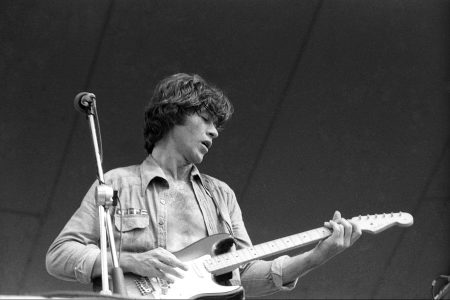

Born in Toronto on July 5, 1943, Robertson joined his first band, Little Caesar and the Consuls, at just13 years old, before leaving to form Robbie and the Rhythm Chords, and later joining the local Toronto group the Suedes, which brought him to the attention of rockabilly wildman Ronnie Hawkins. Far from old enough to drink in the raucous clubs that Hawkins and his band, The Hawks, played, Robertson nonetheless joined up and cut his proverbial teeth with the group, which included drummer Levon Helm and, eventually, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson, before leading a mutiny in 1964.

The next year, Robertson joined Bob Dylan’s newly electric backing band, and brought along Helm — and eventually the rest of the Hawks — for tours of the U.S., U.K., Europe and Australia, where they were both revered and reviled.

“What we were doing, nobody, nobody had quite done that before,” Robertson told me in 2016. “It was a different approach to the music. It had a dynamic thing to it, and an explosive thing to it, and a raging thing to it. It had a violent quality along the way to trying to find the beauty.”

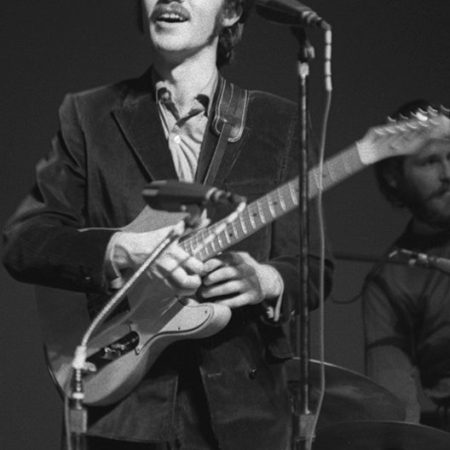

By 1966, both Dylan and the members of the Hawks were burned out, and settled near Woodstock, then a burgeoning artistic community about 100 miles north of New York City, as a retreat. It was there that they set up a makeshift recording studio in the basement of the salmon-colored house the Hawks shared, where Dylan would regularly visit to make the raw recordings — eventually known as the “Basement Tapes” — that came to be revered first by the rock cognoscenti, and later Dylan fans around the world.

“We got launched, we got united with Ronnie Hawkins and then with Bob Dylan,” Robertson told me in 2019. “That was a detour from the mission, but it doesn’t get much more interesting as far as detours go. But after the detour, we got down to business, to doing and inventing and discovering who we really were musically.”

“When we found Big Pink, we found a clubhouse, a workshop, a sanctuary,” Robertson continued on in that same interview. “That was where the brotherhood blossomed.”

The Band released their debut album, Music From Big Pink, in 1968. It included the instant-classic “The Weight” and songs mostly penned by Robertson. It was a watershed in popular music and became the pivot away from psychedelic rock, creating what is now known as Americana in the process.

“The limitations of a basement, where these songs originally came to life, can work in your favor, in a way that you’re doing something that the environment provides, so there was value in that,” Robertson recalled to me of the unusual circumstances under which The Band found their collective sound. “What we discovered was that the communication in the music was something that went deeper inside of us than it ever had been before. Because when you add everything together, each thing plays a part in what you’re creating. So, the fact that we were isolated up in the mountains, and away from the rest of the world, helped us find our own sound.”

As it turned out, The Band didn’t sound quite like any other band, before or since.

“There are people who will work their lives away in vain and not touch it,” Al Kooper, the man famous for the propulsive organ on Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone,” wrote in his five-star review of the album in Rolling Stone. “These are fiery ingredients and (the) results can be expected to be explosive.”

George Harrison, who had visited Dylan and The Band in Woodstock just prior to The Beatles’ January 1969 sessions chronicled in Peter Jackson’s recent documentary Get Back, was inspired by precisely that timeless quality and returned to London extolling the virtues of The Band’s loose, soulful sound and idiosyncratic, collective harmonies. Fittingly, you can hear The Band’s influence, especially that unique harmony blend, pop up throughout the film. Eric Clapton has said many times he wanted to quit Cream and join The Band, but that they turned him down.

“Before Music From Big Pink, most bands would get together and say, ‘Let’s take off our shirts and get a record deal,’” Robertson told me in 2019. “We weren’t cut from that cloth at all. This was not a pop enterprise. This was not a rock-star ambition. This only had to do with all the music that we had gathered, and we had inside of us, and finding how to let it out in a universal way.”

Robertson would contribute to six more Band albums before leaving the group for good in 1978, after The Last Waltz, the film and record of the Thanksgiving 1976 all-star valedictory by The Band.

“When hard drugs stepped in, it got really dark,” Robertson told me in 2021. “For me, getting the guys together was more difficult than it had been in the past. I didn’t like that.”

The Last Waltz was also the first of many collaborations with Scorsese, who directed the concert film. The pair teamed up many times over the years, with Robertson producing the music for or scoring many of the director’s films, including Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1982) and The Color of Money (1986), and, later, Gangs of New York (2002), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and The Irishman (2019). Scorsese’s upcoming film, Killers of the Flower Moon, scheduled for release later this year, was also scored by Robertson.

“Robbie Robertson was one of my closest friends, a constant in my life and my work,” Scorsese wrote in the immediate aftermath of Robertson’s death. “I could always go to him as a confidante. A collaborator. An advisor. I tried to be the same for him. Long before we ever met, his music played a central role in my life — me and millions and millions of other people all over this world. The Band’s music, and Robbie’s own later solo music, seemed to come from the deepest place at the heart of this continent, its traditions and tragedies and joys. It goes without saying that he was a giant, that his effect on the art form was profound and lasting. There’s never enough time with anyone you love. And I loved Robbie.”

When we last spoke, Robertson, who was exceedingly proud of his Indigenous heritage, had high hopes for what was to be his last project with Scorsese. “I’m about to work on this movie, Killers of the Flower Moon with Martin Scorsese, and I’m going to meet with the Osage people, because I want to do it like something we’ve never heard before and in the most honest fashion ever presented in a movie, which is a big full circle for me,” he said. “And that challenge — that experience — is completely frightening and exciting for me, as much as anything I’ve ever gone into.”

In 1986, Robertson released his debut solo album, the superb Robbie Robertson, followed by the remarkable Storyville, inspired by the music of New Orleans, in 1991. He also contributed to records by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Ringo Starr, Neil Diamond and others, and released four more solo albums, exploring the music of his mother’s culture on 1994’s Music for The Native Americans, and electronica on Contact from the Underworld of Redboy in 1998. In 2011, he released How to Become Clairvoyant, and his most recent album, the elegiac Sinematic, arrived in 2019, at the same time as the documentary film about his days in The Band that he’d shepherded, Once Were Brothers, both of which included his ode to his bandmates of the same name.

It was, all in all, a remarkable career from a remarkable man. And Robertson was adamant in one of our last conversations that, although he occasionally collaborated with his former bandmates over the years, it never felt right to quite literally get The Band back together.

“When we were no longer together, years after not being together and still, as Levon says in the Once Were Brothers documentary, once it was gone, it was too difficult to bring it all back together again,” Robertson recalled in 2021. “And with that came distance, and people going through their own issues and everything. That leads to something that has nothing to do with the harmony and the connection and the musical brotherhood that we had for all those years being together.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)