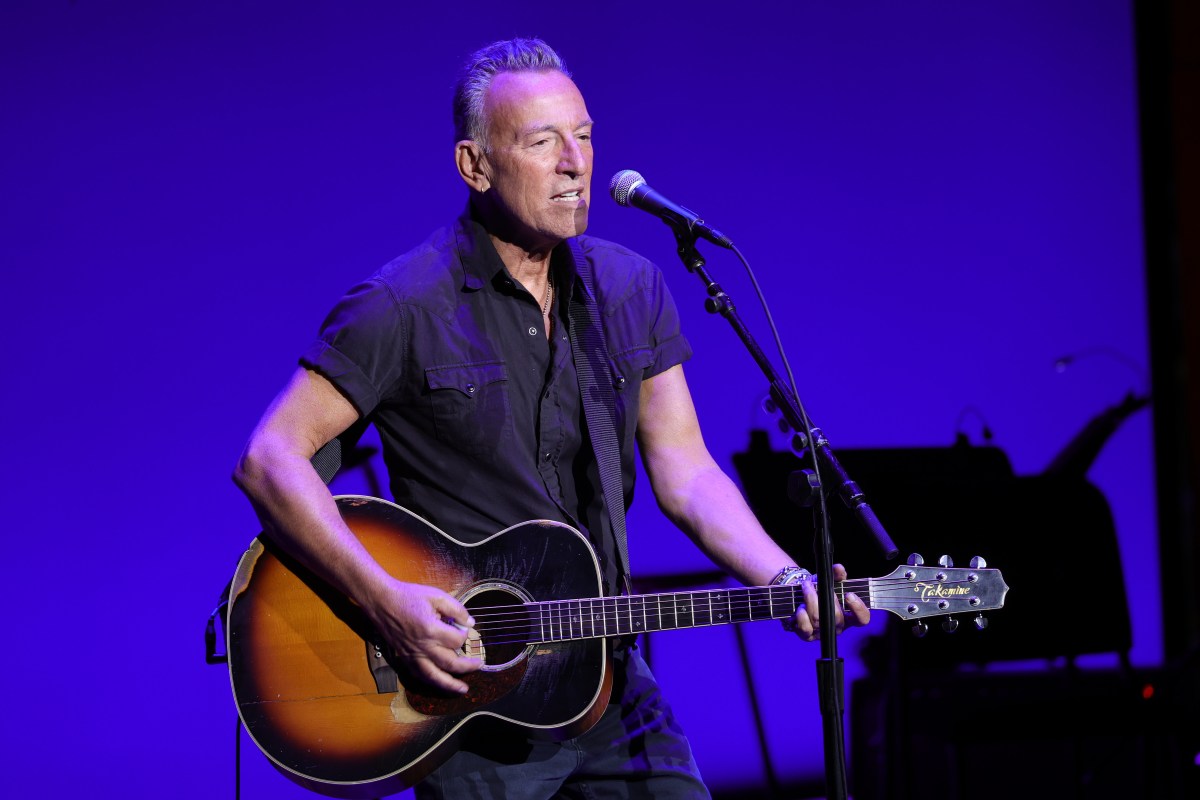

Earlier this month, Bruce Springsteen made history by selling his entire body of work — his songwriting catalog and his masters — to Sony for a reported $550 million. The Springsteen deal is by far the biggest of its kind, but just the latest example of what has become a growing trend: rock stars of a certain age cashing out by selling their publishing rights for massive sums of money.

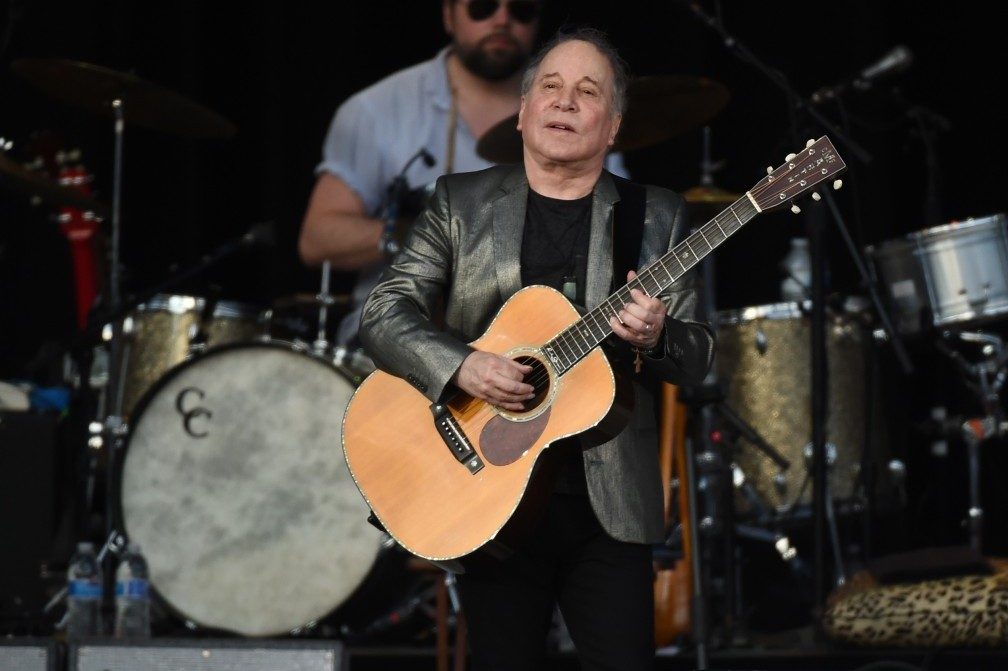

Last year, Bob Dylan sold his entire songwriting catalog to Universal Music Publishing for upwards of $300 million. Neil Young, Stevie Nicks, Paul Simon, Tina Turner, the Beach Boys and David Crosby all followed suit with similar deals. But why, all of a sudden, are investors so willing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on song catalogs?

According to David Chidekel, a partner at Early Sullivan Wright Gizer & McRae LLP who represents clients in the media and entertainment industries and has overseen countless deals related to intellectual property and licensing matters, the rise of streaming revenue as well as blockchain technology, cryptocurrency and NFTs is likely a factor.

“I think investors are starting to believe that there’s going to be an upsurge of different ways to exploit content that didn’t exist before,” Chidekel tells InsideHook. “They’re making a bet that if they get in now, the long tail’s not going to go down, it’s going to go up, at least to some extent, and then they’ll be able to sell their assets at some point to somebody else for much more than they paid for it. That’s the gamble.”

Of course, only time will tell whether or not that gamble will pay off, but even given the enduring popularity of an artist like Springsteen, it’s hard to imagine a company like Sony getting a favorable return on a $550 million investment. But as Chidekel points out, that’s not necessarily the point.

“They’ll never get their money back, but they don’t care because they have a strategic reason for doing it,” he explains. “It’s not about an ROI on that investment, because any financier looking at a deal would say, ‘Wait a minute, this thing makes X amount a year. You’re paying how much times X? How do you get your money back ever?’ You can’t. The company paying the ridiculous amounts of money has a strategic need to have that particular thing, because they know with that particular thing, they can sell their company for a ridiculous amount of money to somebody else. It’s not just that transaction. It’s not just a dollar-for-dollar ROI kind of conversation. It’s more of a strategic, ‘We want market share. We don’t care what we spend. We don’t care if we’re profitable. We want to say we have 45% of the market of blah, blah, blah. So this fills that in for us, checks that box.’ So I think that’s probably what this was. Whoever promoted this internally at Sony, there’s a strategic reason why they did this.”

Meanwhile, from the artists’ perspective, that kind of money is simply too good to pass up. Especially for older artists whose commercial appeal may begin to wane as they age, it’s an opportunity to get their estate in order. As Chidekel puts it, Springsteen likely couldn’t turn down a deal that would give his family everything they could ever need long after he’s gone.

“He’s not a kid,” he says. “He’s getting older, he’s got a family and stuff. And it’s like, ‘If I lock this in right now, half a billion or more, then I know they’re taken care of. If I don’t do that, bad things could happen after I’m gone. Somebody could just do all kinds of terrible things to the library and it [could] have no value and my kids lose out.’ You know what I mean? Unscrupulous representatives or stupid family members. This way, they can’t screw it up. He knows the family’s taken care of.”

In fact, Chidekel recommends that artists wait until they’re around Springsteen’s age or older if they’re considering selling their catalog. “I wouldn’t recommend anyone sell anything when they’re young, because you don’t know what your catalog is going to be,” he says. “If you have two hit songs, someone will give you a little bit of money for it. They’ll buy a piece of it for a little bit. But if you have 20 hit songs, you can get so much more. Give it time.”

Of course, the biggest criticism of deals like Springsteen’s is that artists are somehow “selling out” by surrendering the rights to their life’s work. It’s a fair point, but many of them include stipulations about how exactly the music can be used. “From what I hear, Springsteen was able to get a number of marketing restrictions, which probably made him comfortable with it,” Chidekel says. “Like, ‘Yeah, I’ll sell you my stuff, but you can’t use it for political ads without asking my permission. You can’t use it for religious stuff without my permission.’ Stuff like that. From what I understand, he got a bunch of that, those type of marketing restrictions. Without those, maybe he wouldn’t have done it.”

Ultimately, he says, it’s those restrictions that make him comfortable advising his clients to consider selling their catalogs.

“I think the key questions [for a client considering selling] are, is there a way for you to license it as opposed to selling it outright? If not, okay, you got to sell it,” he explains. “If you sell it, can you get a reversion? Meaning, can you get the rights back after a certain amount of time? If the answer is no to that, and the only option is I have to sell this thing, then I would say, first of all, how much money are you getting for it? I would be wary of anyone not putting enough money on the table. I would be wary of anyone that wouldn’t agree to marketing restrictions — I would never do that. I’d say if the money’s enough, then you take it and then you can do other things with it. And as long as you know they’re not going to do things with your art that are going to make you upset, let it go.”

After all, there’s something to be said for striking while the iron is hot, and Chidekel says the success (or lack thereof) of the Springsteen/Sony deal will likely have a big impact on how many more companies are willing to invest in songwriting catalogs in the coming years.

“If Sony is doing great with it, then you’ll see more and more and more,” he says. “If Sony, two years from now, has been a disaster, we’re going to see less and less and less.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.