Emo Night goes by a few different names, but you can expect some consistency across its various iterations: goth-lite cosplay, impassioned sing-alongs and drink specials with names like Story of the Beer. Emo Nite LA was the first to offer branded merch, including a t-shirt that said “SAD AS FUCK.” Then they began touring the country, despite their performance being little more than two dudes presiding over a Spotify playlist. Then, in 2022, they played Coachella.

Emo nostalgia is big business. My Chemical Romance spent last fall playing packed arenas. Next October’s sold out When We Were Young festival features a lineup of Warped Tour alumni. Even the biggest names in pop music have taken note, with acts like Olivia Rodrigo, Machine Gun Kelly and willow rehashing the sounds of the early 2000s.

Emo purists trace the genre’s roots back to DC’s storied hardcore scene, pointing to Rites of Spring and Embrace as the originators. And they’ll tell you about the twinkly second-wave in the Midwest, and they’ll probably even mention how the genre’s fifth-wave is thriving as we speak thanks to a passionate fanbase who wouldn’t be caught dead at an Emo Night. But this context is largely irrelevant for the Emo Industrial Complex. Like Woodstock for Boomers or grunge for Gen-Xers, emo has become a lucrative nostalgia product for Millennials, promising them trips out of the tumultuous present and back to the more innocent past. Remember this song? Remember When We Were Young? Remember when the biggest problem was feeling SAD AS FUCK? Here’s a t-shirt.

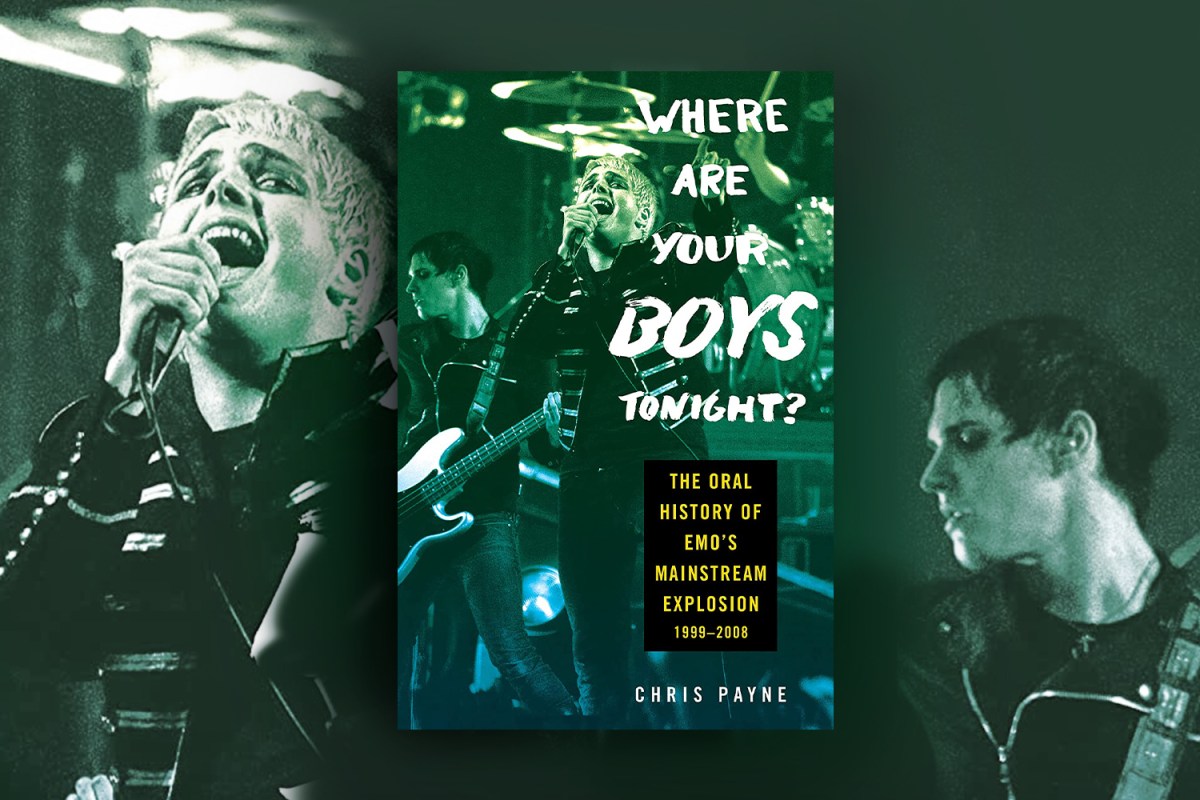

Despite all of the shameless commercialism, an unexpected upside of emo nostalgia is the influx of thought-provoking books about the genre’s history and resurgence. The best among them are Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, a poetic collection of essays, and Dan Ozzi’s SELLOUT, a deeply-researched and often heartbreaking history of the ethics and economics of bands in the scene. Chris Payne’s Where Are Your Boys Tonight?: The Oral History of Emo’s Mainstream Explosion 1999-2008 is the latest addition to the canon, tracking the rise of emo’s third-wave from its humble beginnings in New Jersey basements to its dominance on TRL. For someone like me, who spent his early teenage years attending shows at the local VFW and obsessively checking the Drive Thru Records Yahoo! group, Payne’s book is a cross between a highly specific soap opera and a highly effective time-machine. I geeked out at the recording of Through Being Cool, remembering the way I’d listen to it every night before falling asleep. I lapped up the endless drama around the Long Island bands, recalling the many theories my friends had about the not-so-subtle diss tracks on Your Favorite Weapon and Tell All Your Friends.

Enjoying the book doesn’t require a familiarity with its subjects, though if you previously had an aversion to, say, Dashboard Confessional, I can’t imagine your interest in learning the kids from MTV Unplugged had to sing “Screaming Infidelities” seven times. Still, neutral readers looking for an engrossing read will find a lot to appreciate thanks to Payne’s curation, which emphasizes the scene’s most colorful characters and their intriguing storylines. There’s the Used’s Bert McCracken, whose quick rise to fame is complicated by his struggle with addiction. There’s Victory Records’ Tony Brummel, whose knack for discovering acts is matched only by the mob-like vindictiveness he reserves for those he deems disloyal. There’s hardcore kid turned capitalist-in-chief Pete Wentz, who concocts a hilariously dumb (and ultimately unsuccessful) scheme to have Fall Out Boy play on all seven continents.

Oral histories are suddenly everywhere due to the success of Lizzy Goodman’s Meet Me in the Bathroom, which sparked a different kind of nostalgia. Goodman’s book isn’t mentioned in Where Are Your Boys Tonight?, but the post-9/11 New York scene she documented looms large in Payne’s interviews. It’s not lost on emo’s biggest stars that they were never taken seriously by critics like Pitchfork, who heaped praise on the Strokes and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. “To this day, so many people try to fight off that emo tag,” Bayside’s Anthony Raneri says. “It’s because of those early 2000s hipsters thinking it’s not cool.”

In recounting their histories, third-wave emo’s unlikely stars sense an opportunity to correct the narrative. They did something important, not just something successful. They made great art, not just teenaged melodrama. Who can blame them? Everyone wants to think they’ve dedicated themselves to a noble cause. And, listen, there are legitimately great records from the time period, ones that tackle heartbreak, mental illness and politics in ways that were cathartic for millions of young people.

But in arguing their case, most of the voices in Where Are Your Boys Tonight? neglect an important truth. The music may have been cathartic, but it could also be damaging. Many of the era’s songs are overtly misognyistic, with lyrics that fantasize about women being ridiculed, murdered and dismembered. “We’re vessels redeemed in the light of boy-love,” rock critic Jessica Hooper wrote in 2003 about emo’s ascendance. “On a pedestal, on our backs. Muses at best. Cum rags or invisible at worst.”

Why Are So Many Pop-Punk Songs from 20 Years Ago Beloved by Incels?

From “Teenage Dirtbag” to “Flavor of the Weak,” a startling number of early-aughts anthems center on losers being ignored by girls they feel entitled toFor his part, Payne doesn’t shy away from the genre’s toxic elements. Music journalists Leslie Simon and Jenn Pelly detail the ways the subculture’s misogyny affected their work and their lives. Paramore’s Hayley Williams speaks on how she internalized the scene’s sexism, something she said came with being one of the few women on stage. And Payne highlights the unseen women who contributed to emo’s explosion, like the Bergenfield Girls, an all-female booking collective who helped lay the groundwork for the genre’s success. “Without women,” writer Maria Sherman says in one of the book’s final chapters, “this shit wouldn’t have blown up to the size it did.”

Things get more complicated when it comes to Brand New, whose lead singer Jesse Lacey was accused of sexual exploitation of minors, including exchanging illicit messages with underage fans. More than any other band from this era, Brand New evolved with their fans, growing into a knotty act who resisted nostalgia. In 2017, just months before the allegations against Lacey hit the internet, the band even received a Best New Music distinction from Pitchfork, signifying a level of critical acceptance that had eluded so many of their peers.

In his introduction, Payne addresses the book’s handling of Lacey and Brand New, explaining he’d attempted to square the band’s legacy alongside the allegations from multiple women. “Brand New was arguably the most innovative and critically acclaimed band of their scene,” he writes. “Their appeal was so cultish and specific it’s hard to put into words.” I was struck by that last sentence. Why was their appeal so hard to put into words? I wondered if Payne was grappling with a bigger question, one I’d asked myself in spite of believing all the terrible details in the Lacey allegations: why do I still like this music?

That’s the question Claire Dederer tries to answer in her latest book, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. Throughout the collection of essays, Dederer details the ways her favorite art has been colored by “the stain” of its creators’ problematic biographies, with essays on Roman Polanski, J.K. Rowling, Woody Allen and others. “When someone says we ought to separate the art from the artist, they’re saying: Remove the stain. Let the work be unstained,” she writes. “But that’s not how stains work.” As I was reading, I thought of “Me vs. Maradona vs. Elvis,” a Brand New song that feels especially sinister after reading the allegations against Lacey.

Monsters suggests our problem is one of intellectual arrogance: we’ve tried to establish an unrealistic ethical paradigm for responsibly consuming art. But, as Dederer points out, “It’s not a philosophical query; it’s an emotional one.” She wrestles with admiring Chinatown despite Polanski’s notorious history, with appreciating the magical world of J.K. Rowling created for queer kids even though she’s appalled by the author’s transphobia.

Dederer doesn’t argue we should ignore or downplay an artist’s transgressions so we can enjoy the work in peace. In the age of the internet, biography is unavoidable and, often times, important. But for Dederer, so is beauty. In her estimation, both of those things can coexist for a fan, even when they are at odds. “This tension — between what I’ve been through as a woman and the fact that I want to experience the freedom and beauty and grandeur and strangeness of great art,” Dederer writes, “this is at the heart of the matter.”

So, is Brand New great art? Is the playground juvenalia and casual sexism of so many third-wave emo songs great art? Am I really using the phrase great art and the words Hawthorne Heights in the same sentence?

Dederer isn’t writing about Jesse Lacey or emo, but she might as well be. “What makes great art depends on who we are and what we live through,” she writes. “It depends on our feelings.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)