This is the third volume of a weeklong series on the theme of fatherhood in the work of six contemporary filmmakers. You can read the rest here.

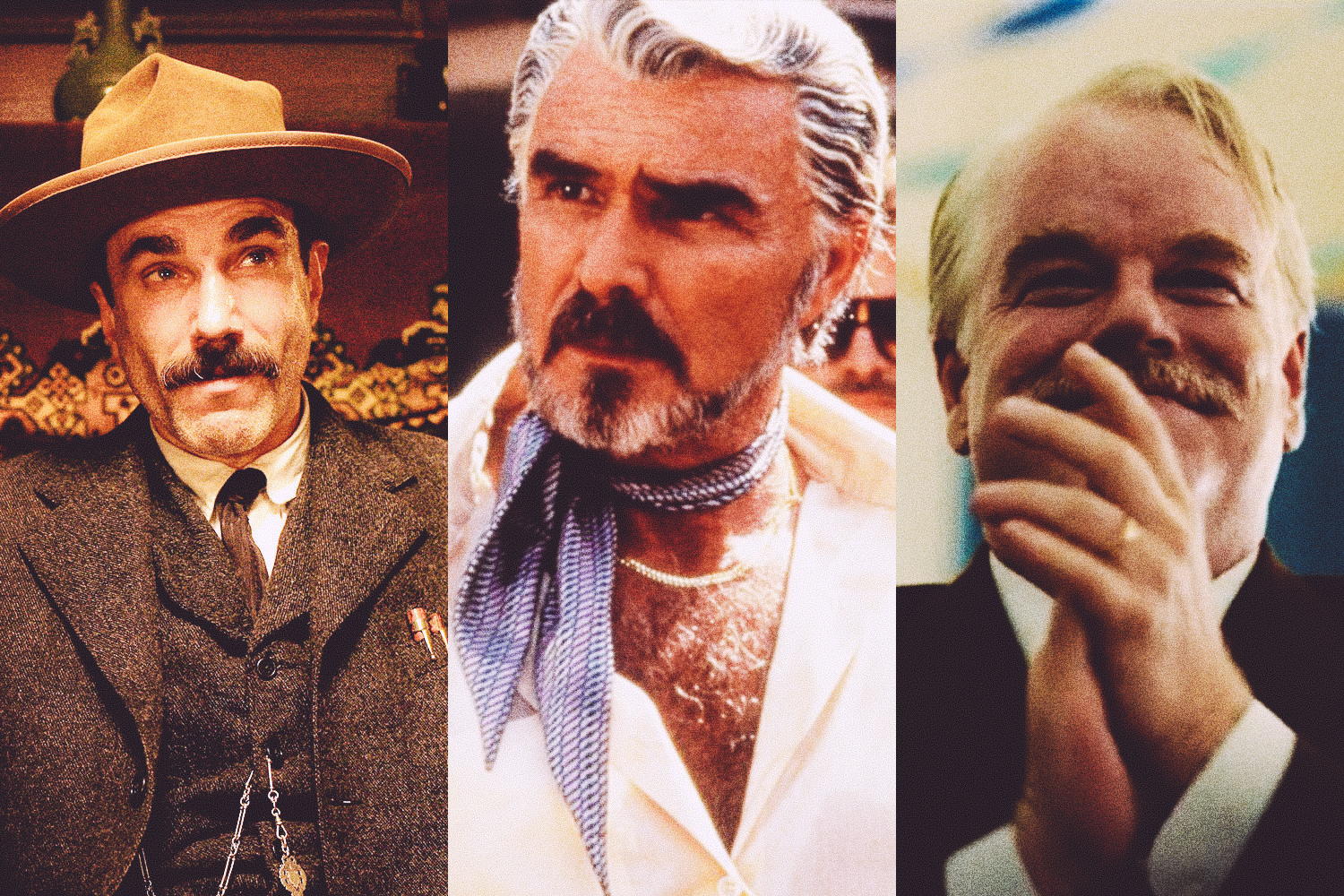

In the film world, there are few father-daughter relationships as high-profile or as thoroughly committed to celluloid as the one between Francis Ford Coppola and his daughter Sofia. After cameoing as an infant in The Godfather, their working partnership began in earnest by 1990, when a 19-year-old Sofia starred in the maligned Godfather Part III as a last-minute replacement for Winona Ryder, who had fallen ill and needed to be replaced. In her pouting, cherub-cheeked role as Mary Corleone, she becomes a fallen angel, taking a bullet intended for her father Michael in an operatic conclusion of fated proportions. But the reviews were often cruel, even accusing Sofia’s performance of nearly ruining the film in some of the most acrid instances.

In a recent interview around the release of his dramatically recut version of the trilogy’s concluding film, named The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, Coppola expressed regret for putting his teenage daughter through the strain of public ridicule. ‘‘When the film came out, the bullets that Sofia got were meant for me, just as in the story, ironically,” he told The Hollywood Reporter. For her part, Sofia seems philosophical about the situation, at least in retrospect. She recently told the New York Times, “It wasn’t my dream to be an actress, so I wasn’t crushed. I had other interests. It didn’t destroy me.” If anything, it provided a certain hardiness for a young woman who wanted to one day make films herself and put them out into a world bound to be all the more judgmental because of her family name.

Sofia’s filmmaking career began in earnest with her 1999 feature debut, The Virgin Suicides, a gauzily pretty look into the dark heart of teenage girldom. She adapted the script from the Jeffrey Eugenides novel without direct help from producer-to-be Francis Ford Coppola or his team, which allowed his daughter to light out on her own in preemptive defiance of the inevitable nepotism charges. Still, whether she liked it or not, her career would be seen in the long shadow of her father for some time to come. That may have been unfair, it may have been unavoidable, but in an artistic sense, it’s also true that Sofia’s uniquely privileged life — and her relationship with her dad — has obliquely informed many of the stories she’s chosen to tell.

Inasmuch as an outsider can ever guess, growing up as a Coppola seems to have hinged on the tension between her enormous privilege and the surreal, destabilizing effect of celebrity on a parent-child relationship. Sofia interned at Chanel as a teenager, had the backing of her father’s production company American Zoetrope on all of her films, and, of course, enjoyed the mentorship of one of America’s finest directors. But there were pitfalls: Sofia’s older brother Gio died in a boating accident when she was 15 (the miasma of grief in The Virgin Suicides certainly seems lived-in, in that sense); her parents were often at odds over her father’s many affairs. And if her movies are anything to go by, there’s a certain distance between parent and child when your famous dad’s love and attention is craved by every other person he meets.

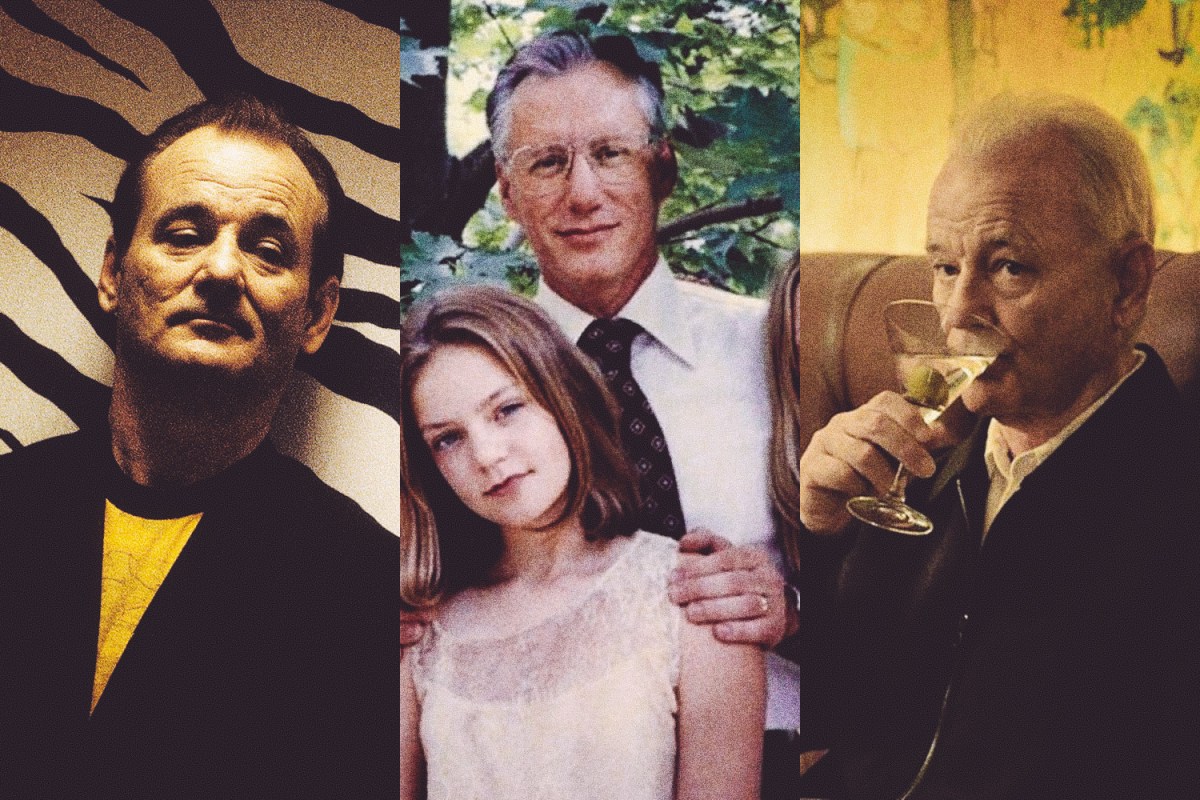

From Lost in Translation (2003) straight through to her most recent drama On the Rocks (2020), Coppola’s films have engaged with the role of the father and the father figure as a matter of subtle urgency. In Lost in Translation, a film that Coppola has referred to as “personal,” the transitory friendship/never-consummated-kinda-romance between Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson is heightened by their age difference. For the young wife, bored and neglected by her husband in a Tokyo hotel, the older man’s affection and friendship seem like enough. Coppola lenses well-heeled female isolation with the eye of someone who knows it inside out.

It doesn’t seem like a total coincidence that Coppola cast Bill Murray again in her bittersweet comedy On the Rocks, this time as a literal father to her protagonist (Rashida Jones). He tries to help her iron out the increasingly worrying wrinkles in her marriage, and the pair zip around New York City, bickering while they track down her possibly-errant husband. The mood between the pair volleys between recrimination and affection, particularly in light of the fact that the father himself has clearly been a philanderer and big shot for most of his daughter’s youth. “It must be very nice to be you,” Rashida Jones says to Murray at one point, with a shimmer of genuine annoyance that can’t help but to strike right down to the centre of her feelings.

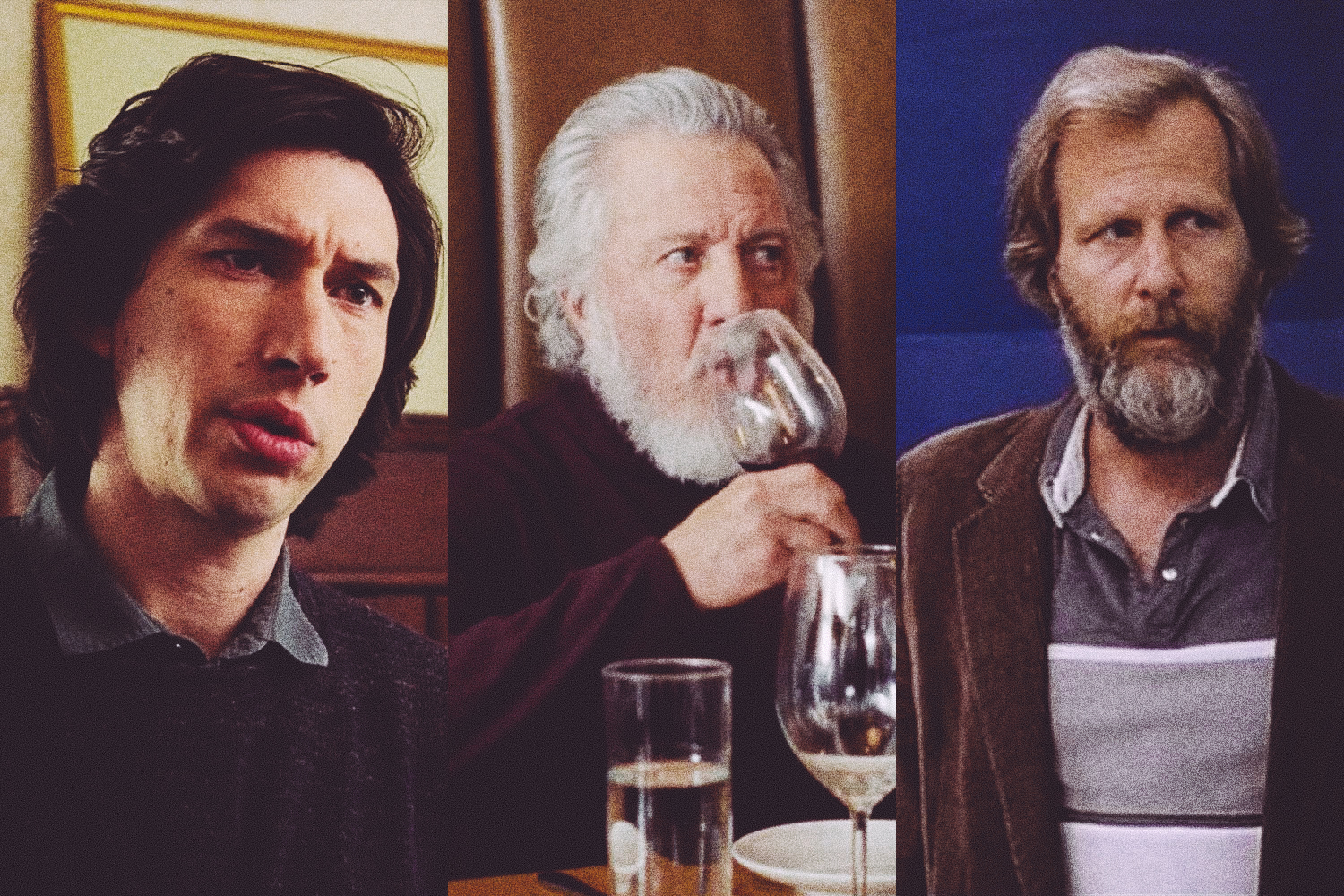

Perhaps the film wherein Coppola most directly explores the father-daughter dynamic is the excellent, minor-key drama Somewhere (2010). Spare and elegant, the film traces a few days in the life of John Marco (Stephen Dorff), a wild and washed-up actor spending time in that famed Los Angeles den of iniquity, the Chateau Marmont. When his 11-year-old daughter Clio (Elle Fanning) unexpectedly comes to call, he has to at least go through the motions of pretending to get his act together. As the pair fritter the days away by the pool in a luxurious boredom, their gradual reversals of role — from a needy daughter and distant father to a clinging father and caretaking daughter — grow increasingly apparent.

Chateau Marmont was a haunt and hangout for Francis when Sofia was young, and she spent a lot of time around the grounds, watching the Hollywood circus go by. She says it was there her father taught her how to play craps; one can imagine that she saw a lot at a young age. While never cranking up the woe-is-me stuff, Somewhere shows the empty glamor of Hollywood with real ambivalence, and depicts it not with nihilist bombast but with the denatured, jaded eye of someone long familiar with this world’s rhythms. Seen through from the vantage of a young girl who already seems exhausted by her surroundings and desperate for her father’s undivided attention, the real-world parallels invite themselves.

Ultimately, with eight features under her belt, Sofia Coppola has largely stayed true to the old canard about writing what you know, even if not in an explicitly literal sense. Her female protagonists tend to be pampered, but also dogged by emptiness and yearning that, at its best, can resonate beyond the director’s own background. That unquenchable need is pointed towards paternal figures so frequently throughout her work; it’s as if her elliptical and poetic film style, often relishing in the space between conversation, seems to put her in communication with her father in a way words might never achieve.

That Sofia has managed to rise above the obvious portrayal of a Hollywood brat often leveled at her and come into her own as a writer-director — to the extent that when someone mentions a Coppola film, we have more and more cause to ask “Which one?” — is a testament to both her tenacity and skill. She takes advice from her dad and regularly shares her work with him, but ultimately, her art is her own.

“I’m proud to be his daughter,” Sofia told The Guardian in 2017. “I learned to have balls from him, and integrity. But I have a body of work now, and it has its own identity. He’s a great master, but I’m happy to carve out my own way of working.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.