This is the first volume of a weeklong series on the theme of fatherhood in the work of six contemporary filmmakers. Check back here tomorrow for more.

Paul Thomas Anderson doesn’t talk much about his family, the topic on which his work invites the most personal speculation. The eight features he’s directed are littered with mothers and fathers both biological and surrogate, organized under the uniting principle that positively or negatively, the relationship between parent and child must be intensely intimate. But in the 1999 profile “His Way” that the New York Times ran during the 1999 release cycle for Magnolia, this aspect of his background gets little more than a glance: “He has a troubled relationship with his mother that he won’t discuss and was very close to his father, who died in 1997.” In 2018, the Guardian’s interview pegged to Phantom Thread described him as “raised Catholic by a voice-actor father he adored and a mother he didn’t so much.” Anderson has recalled that his father, the voice actor and Hollywood fixture Ernie Anderson, “always encouraged me to be a writer or director.” The most substantive impression of his mother, an actress born Edwina Gough with a handful of commercials and bit parts in the ‘70s to her name, comes from a 1975 piece in Cleveland Magazine. “Ernie is lazy,” she said at the time, her intended ratio of sincerity to sarcasm not fully clear. “Really lazy.” They divorced in the mid-‘90s.

The grand arc of Anderson’s career is that of honing and refinement, as a prodigious talent matured out of the need to prove his ambitions. Punch-Drunk Love bisects his filmography, dividing the audacious, pop-music-packed epics fueled by coke from the more reined-in, opaque films made under the auspices of marijuana. His pet theme of the fraught parent-child bond likewise evolved along these lines, from ragged portraits of rage and desperation to attempts at understanding and empathy. Viewed as a whole, his oeuvre shows an angry young man growing into a juncture from which he’s ready to make peace, letting frustration give way to forgiveness, and in turn, to the fading of feeling that signals true escape from a parent’s stifling influence. His evolving depiction of fathers — capricious, untrustworthy or entirely absent — cuts to the tender, wounded heart of the matter.

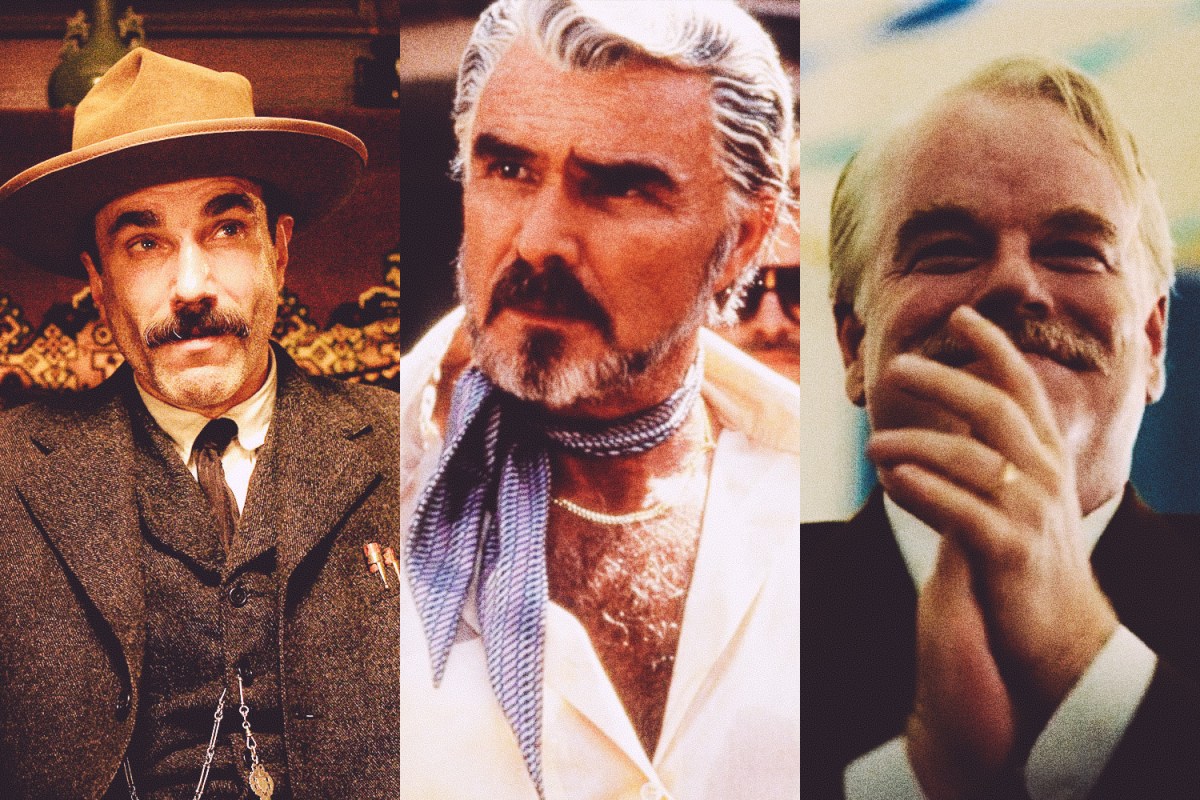

In the loose triptych of Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Magnolia that could be said to comprise “Early PTA,” our existentially wayward protagonists wriggle between neglectful birth parents and the mentors who would come to replace them. Anderson’s splashy debut feature joins John (John C. Reilly) in front of a diner stuck in a desert purgatory, having just laid his mother to rest. Unmoored and placeless, he’s the ideal protege for elder expert gambler Sydney (Phillip Baker Hall), who buys the younger man’s loyalty with a cigarette, a cup of coffee and six thousand dollars for the funeral. The ace up the film’s sleeve is that the paternal partnership that flowers between the two of them is no function of mere chance, Sydney owing John a spiritual debt after having killed the man’s real father years earlier. The daddy-issues transference is more clear-cut than we’d see again from Anderson, the replacement of an ill-fitting blood father with a caring, dutiful father figure one-to-one.

This process would be reiterated with Boogie Nights, for which Burt Reynolds earned an Oscar nomination as the porno paterfamilias Jack Horner. Fresh-faced and well-hung Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg) falls in with Jack’s entourage and is soon rechristened Dirk Diggler, born anew in the womblike waters of a hot tub. Eager to escape a chaotic home life where he’s screamed at by his castrating mother (cherished character actress Joanna Gleason) while his neutered father sits mute listening to them from the next room, he moves in with Jack, forming a cheekily incestuous nuclear unit with skin-flick queen Amber Waves (Julianne Moore) as Mom and fellow teen Rollergirl (Heather Graham) as his kissin’ sister. After going through private hells of drugs and self-doubt, they all ultimately have only each other, reuniting in a roving dolly shot that slinks through their palatial L.A. pad, now a home filled with caring and love. There’s a fundamental immaturity to the way Anderson portrays Dirk’s real father and his adopted one as guardians first and foremost, either failing or partially succeeding in shielding the guileless kid from the world’s vicissitudes. The mothers may be a lost cause, but there’s a hope that the fathers can offer protection from them, or at least a belief that they should.

This notion expands to cover the whole of Anderson’s sprawling Magnolia, a lattice of broken relationships that can be traced back to familial dysfunction in every case. The pants-wetting anxiety of boy genius Stanley Spector (Jeremy Blackman), an otherwise unstoppable contestant on the junior quiz show What Do Kids Know?, stems from the selfish pressures placed on him by his money-hungry father (Michael Bowen). He’s another serial neglecter, exploiting instead of looking out for his child, doing in real time what the older men Earl Partridge (Jason Robards, in his final role) and Jimmy Gator (Phillip Baker Hall) must ruefully look back on. Dying of the same cancer that took Ernie Anderson just two years prior, Earl contends with the guilt of having walked out on his wife and son Frank (Tom Cruise) as she passed away all those years ago, an experience that turned Frank into a raging misogynist as an adult. Jimmy has his own demons creeping out of the closet, his molestation of daughter Claudia (Melora Walters) having left her an emotionally stunted coke addict. Parents repeatedly fail their offspring and bequeath personality flaws, the hope of redemption slipping away in their final hours.

The altogether lower-key Punch-Drunk Love offered a brief respite from this fever-pitch filmmaking, and deemphasized the role of the parent. Hapless loser Barry (Adam Sandler) just has seven harpyish sisters to deal with, one of the film’s many departures from what had up to that point been established as Anderson’s signature style. The midpoint of this unexpected borderline romcom heralded a new era that would be characterized by a glowering control over his former messiness and unwieldiness, and his attitude toward lingering resentments in the home followed suit. In There Will Be Blood, one of the key figures in the orbit of ruthless oil baron Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) is his son, the deafened H.W. (played as a lad by Dillon Freasier, then as a grown-up by Russell Harvard). Once a derrick explosion takes his hearing, the boy starts acting out and compels Daniel to ship him off to deaf school in San Francisco, a choice that goes on to torment Daniel for years to come.

Two of the most enjoyable lines to bellow in Day-Lewis voice — “I’ve abandoned my boy!” and “You’re just a bastard in a basket!” — pertain to H.W., charting the corrosion of the bond between them. Daniel yells the first while making a confession he doesn’t really mean to placate preacher Eli (Paul Dano), couching his actual negligence in sarcasm and denial. The second comes in a heated exchange between Daniel and the grown H.W., who’s come to ask his father to dissolve their legal partnership so he can start anew. Daniel has an abusive outburst that culminates in his revealing to H.W. that the boy was adopted, to which the younger man expresses a cold relief. He’s finally free, and we join him in feeling pity for the gnarled shell of a man that Daniel has transformed into, rather than an unproductive anger.

Working toward that liberating resignation constitutes the primary work of The Master, in which the connection between cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and disciple Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) is profound enough to span several lifetimes. In the cock-and-bull riff on Scientology that Dodd runs, they’re linked souls, destined to be involved with one another either as mortal enemies or homoerotically charged companions. Introduced humping a woman made of sand, the animalistic Freddie spends the film trying to work up the self-knowledge and self-actualization to leave the svengali Dodd, who recognized a perfectly impressionable vessel in the lost, uncertain veteran. The closest he comes is in a long-awaited confrontation not unlike that in There Will Be Blood, which also ends with the son figure storming out after a tearful reckoning with the irreparable faults in their relationship. This time, however, the next thing we see is Freddie retreating into his favored vice of sex while reciting the processing questions he originally answered in his intake session with Dodd. It’s a messier, but more honest, and perhaps more freeing conclusion than H.W.’s full detachment, an admission that we must accept that our parents’ presence will persist no matter how hard we try to dispel it.

From the looks of Anderson’s output, that surrender is the only path to living an unbothered life. Inherent Vice goes off and does its own thing, its shaggy stoner mysteries trading familial discord for the romantic kind. Same largely goes for Phantom Thread, the lone appearance of a parent being the spectral image of designer Reynolds Woodcock’s mother. He thinks of her often, but he’s not plagued by her; she’s not a malevolent spirit, merely hovering around and making her memory known. In Anderson’s turbulent oeuvre, that’s as satisfying a victory as a scarred child can hope to claim. After a lifetime of trauma, his characters — and perhaps their creator, as well — attain self-preservation through cutting off without cutting out, going their own way while bringing these formative pieces with them. Though often an accessory to the domineering mother of the house, PTA’s fathers and father figures always brand a lasting imprint on their sons. They can either let it heal and live with the scar, or pick it until it bleeds.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.