This is the second volume of a weeklong series on the theme of fatherhood in the work of six contemporary filmmakers. You can read the rest here.

Noah Baumbach’s father, the late novelist and academic Jonathan Baumbach, cameos in his debut film Kicking and Screaming as a creative writing professor who listens to his students’ inane comments after Grover (Josh Hamilton) reads his latest story. A dutiful son, Noah grants his father his own brief close-up: he derisively rolls his eyes when one undergraduate describes Grover’s prose as “the bastard child of Raymond Carver.” Jonathan makes two other brief, silent cameos in his son’s filmography. The first is minor — he plays the father of Carlos Jacott’s character in the sophomore feature Mr. Jealousy — but the second carries considerable weight. In The Squid and the Whale, his face appears through the window behind a guidance counselor as she informs freshly separated parents, Bernard (Jeff Daniels) and Joan (Laura Linney) Berkman, that their son Frank (Owen Kline) has been masturbating and leaving his semen around the school. Noah frames his father like a spirit, watching over the acrimonious fallout as it unfolds in real time.

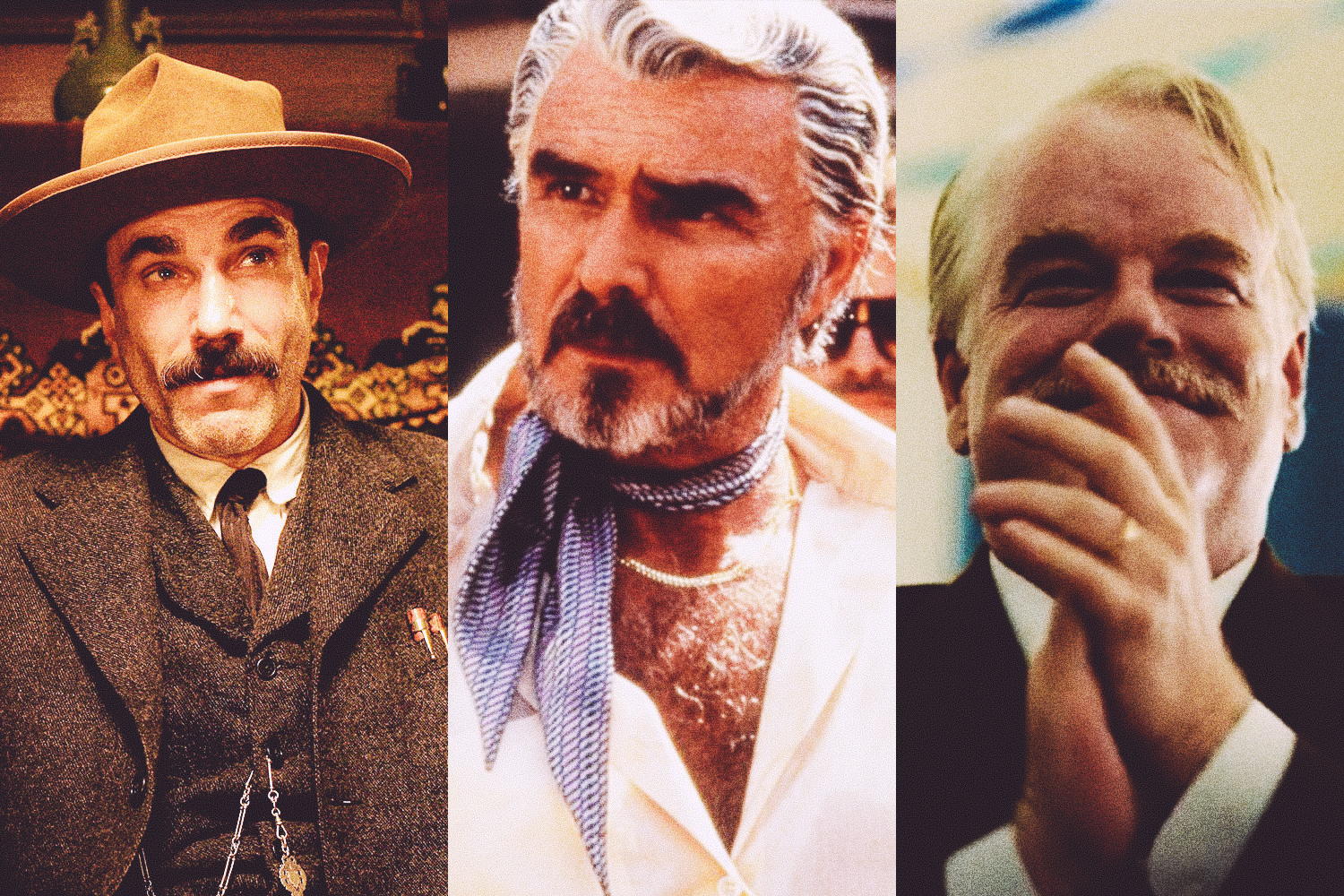

Based upon Noah’s own parents’ divorce, The Squid and the Whale depicts the patriarch Bernard as a pretentious bastard, a washed-up writer who passive-aggressively lashes out at anyone in his path, especially his ex-wife, now enjoying literary success of her own. Frank’s older brother, Walt (Jesse Eisenberg), worships Bernard; he emulates him as much as possible and openly takes his side in the separation. The film primarily traces Walt’s slow disillusionment with his father and ends with him acknowledging Bernard’s self-importance and emotional detachment. When Walt runs to the Natural History Museum and stares directly at the famous squid and whale diorama, something he was too frightened to do as a boy, it’s an indication that he sees his parents with adult eyes, free of adolescent idealization and binary categories. They are flawed, difficult people, just like himself, and it’s unlikely that they’ll ever change.

It’s no secret that much of Noah’s work has been inspired by his own life, though to what degree is purely speculative. In an interview with Jonathan Lethem, he said that The Squid and the Whale was the first script that he didn’t show his parents as he was working on it, desiring to retain his own personal experience. Though it’s unclear how much of Jonathan is in Bernard, the film’s emotions are like an open wound, raw and unfiltered regardless of how much has been invented. Its clipped editing style plays like a series of fractured memories, as if Noah were flipping through a painful scrapbook in his mind. Jonathan haunts every tragicomic moment of The Squid and the Whale, not necessarily in a malicious sense, but like the living ghost of a paterfamilias who has left indelible marks on his son.

Two other fathers in Noah’s films can be interpreted as fictional avatars of his own. The first is Grover’s dad in Kicking and Screaming, a benevolent presence played by Elliott Gould, who briefly visits his son in his dingy off-campus housing. Struggling with a fresh divorce of his own, he relays an uncomfortable sexual situation to Grover before he’s loudly stopped. “I’m not really ready to accept you as a human being yet,” the early twentysomething tells his father.

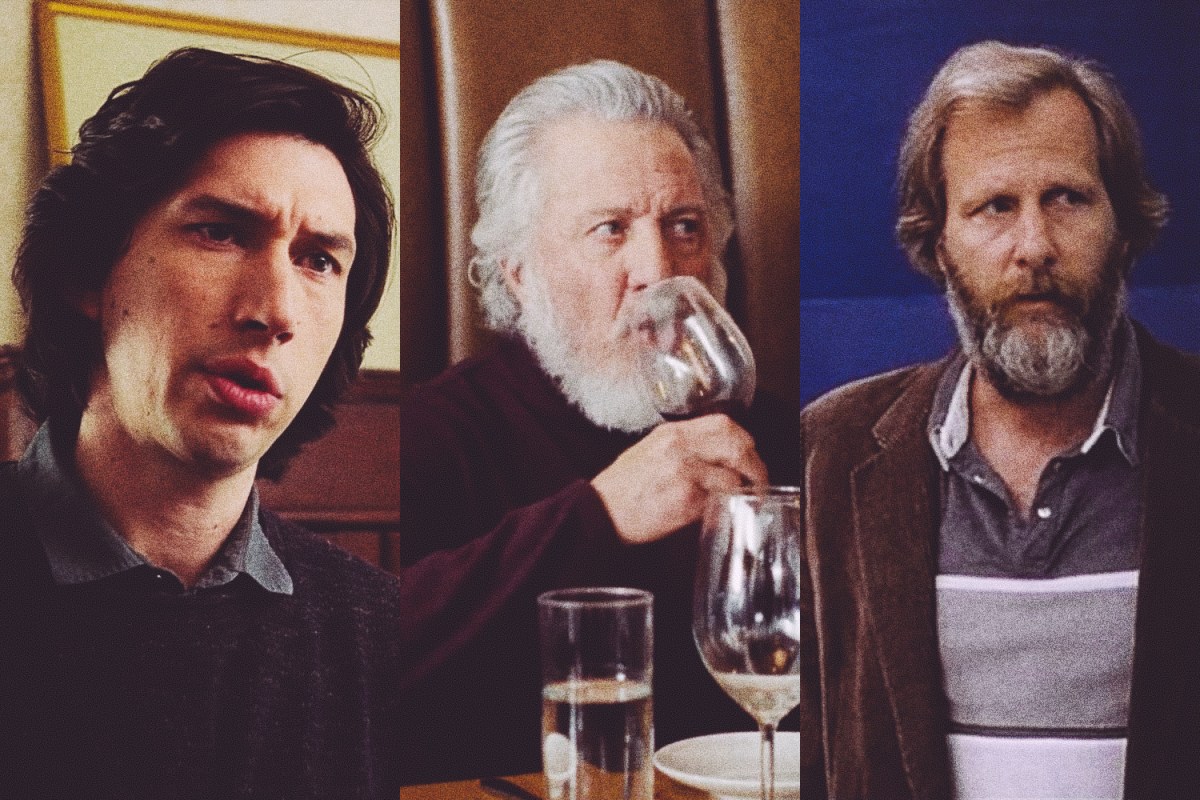

The second is Harold Meyerowitz (Dustin Hoffman) of The Meyerowitz Stories, a bitter, dysfunctional sculptor and retired art professor who exasperates his adult children, all of whom are still dealing with the lingering effects of their difficult childhoods. It’s not an enormous stretch to connect Harold, a thrice divorced artist whose work remains permanently obscure, with Jonathan Baumbach, a thrice divorced writer whose writing has been in and out of print for his entire life. In the second half of Meyerowitz Stories, sons Danny (Adam Sandler) and Matthew (Ben Stiller) Meyerowitz attend a group show celebrating the art of Bard faculty, which includes their father. Under the influence of drugs, they deliver emotional and blisteringly honest speeches about Harold, who is unable to attend because he’s laid up in the hospital with a chronic subdural hematoma. “Maybe I need to believe my dad was a genius because I don’t want his life to be worthless,” Danny tells the uncomfortable audience. “And if he wasn’t a great artist, that means he was just a prick.”

It’s particularly revealing to track Noah’s paternal creations over the course of his career, having begun in such close proximity to his formative years. Kicking and Screaming was released when Noah was 26 years old, and its vision of a father figure is still rooted in childhood sympathy. The Squid and the Whale, the product of a man in his thirties reckoning with his complicated adolescence, hit theaters a decade later. Finally, Meyerowitz Stories premiered at Cannes a few months before Noah’s 48th birthday; it’s the work of a director who, after reaching some peace with his father, is no longer willing to conceal his imperfections or obscure harsh truths. Over the course of 20 years, the dads in his films have become progressively colder and more unpleasant. As much as Noah spotlights Bernard’s obnoxious and cruel behavior, he affords him a few genuinely sympathetic moments. Meanwhile, the only qualities that offset Harold Meyerowitz’s hostility are his age and poor health. This meta-narrative suggests an artist coming to terms with his father’s legacy, making his own estimations about his personality and its mixed effect on his life.

Noah became a dad himself in 2010 before separating from his first wife, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and he recently had another child with his partner, Greta Gerwig. Since then, his films have become populated by fathers near his own age. Though separated from their respective wives, Danny and Matthew are both involved with their children. Danny stays caring and affectionate with his college-bound daughter Eliza (Grace Van Patten), sometimes to a fault, such as when he ferociously chastises her for mixing wine and beer. Meanwhile, Matthew seems more distant with his son Tony, even though he tries to keep in contact with him over FaceTime whenever he’s on the East Coast. Both struggle with maintaining relationships with their kids despite geographical distance and fractured romantic bonds with their mothers, a common scenario for any divorced parent.

Fatherhood necessarily lies at the center of Noah’s divorce drama Marriage Story. Charlie (Adam Driver) struggles to connect with his young son Henry (Azhy Robertson), who gets along much better with his more tender mother Nicole (Scarlett Johansson), especially after their initial separation. He tries to make Henry’s visits fun, but oftentimes he’s stuck carting him between lawyer visits and stringing together a makeshift trick-or-treat outing around L.A. after spending a more traditional Halloween with Nicole’s family. In a particularly piercing moment, Charlie reads Stuart Little to Henry alongside Nicole, but after he’s finished, Henry requests that Dad leave him and Mom alone. Charlie politely acquiesces and Nicole makes excuses for his preference, but Noah treats this as a heartbreaking inevitability of young children, especially sons, living with divorced parents. Henry spends more time with Nicole and thus gets along better with her while Charlie remains on the periphery. Noah never underlines how such distance will affect Henry’s relationship with Charlie as he grows older, or how much Charlie might grow to resent his son for having a stronger relationship with his ex-wife, because there’s simply no way to tell.

The most honest, penetrating insight about parenting in Noah’s work lies in one of his messiest works, While We’re Young, a generations-collide film whose narrative ultimately hinges on questions of documentary ethics. After their friends Fletcher (Adam Horovitz) and Marina (Maria Dizzia) have a baby, Josh (Ben Stiller) and Cordelia (Naomi Watts) start hanging out with a couple in their twenties partially to distract from their childlessness. When Josh gets into a fight with Cordelia, he reconnects with Fletcher, who admits to him that having a kid didn’t really change his perspective all that much. “I love my baby,” he says, “but I’m still the most important person in my life.” Horovitz delivers this line without any regret or guilt, and Noah doesn’t depict the moment as a failure on Fletcher’s part. Rather, it’s an honest perspective that rarely receives its proper due. Parents are not simply extensions of their children. In the end, they remain themselves.

Jonathan might appear as a spooky apparition in The Squid and the Whale, but up until recently, his presence loomed heavily over much of Noah’s career. He moves through his son’s work even as Noah’s own parenting experiences take precedence simply because views of fatherhood are inherited, even when they’re deliberately rejected. The Baumbach films embrace the idiom “the child is the father of the man” to a moving extent. We are still our parents, even as we consciously try to escape their influence.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.