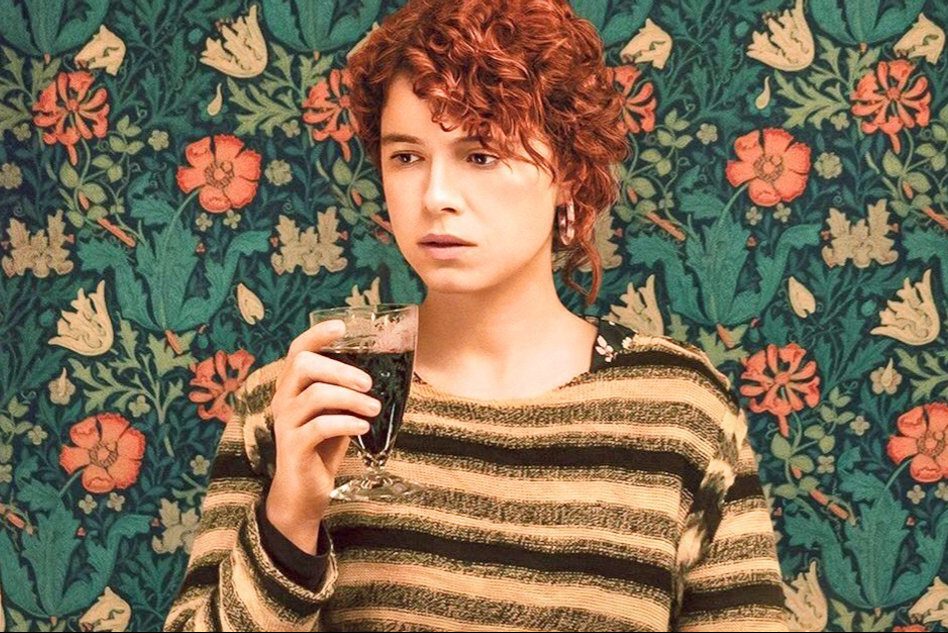

“When we all fall asleep, where do we go?” wondered the philosopher Billie Eilish with the wordy title of her blockbusting debut studio album. The work of her contemporary Charlie Kaufman endeavors to answer a more complicated corollary to that question: Where do we go when we get lost in our thoughts? The idiom implies travel and transportation, the condition under which his beguiling new film I’m Thinking of Ending Things begins. Jake (Jesse Plemons) is bringing his girlfriend (Jessie Buckley, in a role officially labeled “Young Woman”) to his suburban hometown so she can meet his parents (Toni Collette and David Thewlis), a trek that sticks them in the middle of a nighttime blizzard whiting their surroundings out to blackness. She’s wrapped up in her internal monologue and he’s got plenty of his mind as well, but we won’t realize until the revelatory final act just how deep in thought they really are.

Suffice it to say that all the snow harbors a metaphorical significance, like just about everything else in this dense symbolist head-trip. Nothing is as it seems, an overused hook in the movie biz redeemed here by a total commitment to deconstructing the clichéd “It was in their head all along!” twist. Kaufman’s latest blurs the line between reality and our subjective perception of it until it’s been buried completely. What remains once all the powder has settled is the most concentrated realization of his creative sensibility yet, the logical conclusion of his ongoing project to visualize mental interiority as an exterior space. He’s spent his entire career contriving postmodern devices that give physical shape to anxieties and insecurities. Now, he’s finally cut out the intermediary and plunged us all into what Willy Wonka would call “a world of pure imagination,” if the noted candy magnate had had fantasies of suicide instead of chocolate manufacturing.

Kaufman got his start in the crucible of the comedy writers’ room, where his neuroses kept him in polite silence for his first few weeks on staff at Chris Elliott’s cult-favorite sitcom Get A Life. When he did contribute, he wowed his new peers with series highlights like “Prisoner of Love” (in which Elliott’s Chris Peterson gets taken hostage by his recently released prison pen pal) and “1977 2000” (the one where Chris time-travels to stop a disgraced cop pal from making the urine-related mistake that cost him his job). Even when pitting his self-confessed timidity against the jostling attitude of TV production, he got some sublimely strange stuff on the airwaves. “1977 2000” offers an early example of what would become the typical Kaufman approach, in which surrealist touches mold the narrative fabric to match a character’s inner state. Chris, longtime nemesis of his best friend’s humorless wife Sharon, encounters her as a two-headed zombie in this episode. The moment makes only slightly more sense in context, adhering instead to an associative train-of-thought reasoning.

The scribe arrived in grand fashion with the script for Being John Malkovich, directed by simpatico oddball Spike Jonze. The elevator pitch — a sad-sack puppeteer discovers a small door that allows him to share the POV of actor John Malkovich — only teases the sum total of the unconventional in a plot that also includes a post-traumatic chimpanzee, peculiar perspectives on gender and a mysterious cabal of immortal old people. Kaufman eased audiences into his running preoccupation with the life of the mind, articulating his pet theme of psychology inhabited secondhand by literally mashing up bodies and consciousnesses. The key scene sees Malkovich triggering an ouroboric glitch by entering the door to his own self, a feedback loop putting his cue-balled head on the bodies of everyone in sight. They all speak only with the word “Malkovich,” immersing him in himself to hilarious, eerie, and discomfiting effect.

Every one of Kaufman’s works eventually arrives at this unsettling existential juncture, where the protagonist finds their identity or aspects of it seeping into people who are not them. Nicolas Cage, the most versatile actor to have ever lived, manifests warring selves housed within the “Charlie Kaufman” persona as the foundation for sophomore feature Adaptation. With a paunchy prosthetic suit and thinning hairpiece, he plays onscreen avatar “Charlie” as a bundle of worries, the yin to the confident, carefree and successful yang of twin brother “Donald.” The parts of himself that Charlie resents most collide with the parts of others that resents most, Donald’s self-assurance exacerbating his lack thereof. Moreso than the invisible hand of god, those bastards called other people can be relied on for a steady supply of humiliation, as if they’ve been briefed on all our weak spots.

Personhood has always been the most malleable quality under Kaufman’s laws of fiction physics, liable to mutate and splinter into unfamiliar new forms. He peppers his films with allusions to Fregoli and Capgras, namesakes for delusions warping the way we process presences outside our own. (The former refers to the condition of believing that other faces are all one trickster constantly changing disguises, and the latter, to the belief that someone close to you has been replaced by an identical impostor.) His directorial debut Synecdoche, New York abounds with doubles and doppelgängers, as theater director Caden Cotard (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) mounts a play covering all of creation. This quixotic mission requires him to cast an actor to portray himself, and an actor to portray that actor, and so on and so forth. In fact, “and so on and so forth” may be the closest thing Kaufman has to a motto, his earlier thought experiments structured in concentric metatextual circles that must include smaller versions of themselves.

That unsparing self-interrogation was mistaken for navel-gazing by many of Kaufman’s harsher critics, and his choice to insert himself into his writing got the charge bumped up to narcissism. All of which made 2004’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind an anomaly in Kaufman’s corpus of nobly uncommercial hard sells: an Oscar-winning box-office success. This critic’s theory as to why audiences responded to the tale of dissolving couple Joel (Jim Carrey) and Clementine (Kate Winslet) has to do with its foregrounding of wistful lost love, a constant for the auteur made clearer and more sympathetic in this instance. It mostly boils down to “Why doesn’t she love me?” being a slightly more flattering strain of anguish than “Why won’t anyone love me?” The rest of it stems from Kaufman’s shift from remaking characters in his protagonists’ images to doing the same with setting.

In that film, a company called Lacuna erases painful recollections for pay using complex gadgetry which jettisons Joel into a Proustian vortex of longing and regret. His process of tunneling through his own subconscious steered Kaufman’s filmography in more abstract directions, toward an oneiric atmosphere reprised in 2015’s stop-motion wonder Anomalisa. The two films share a certain spatial blurriness, as character and viewer tumble through liminal half-places that may or may not be corporeal. In his film Inception, good ol’ Christopher Nolan described the essence of a dream as being somewhere else without knowing how you got there. Despite skewering Nolan as the Starbucks of filmmakers in his lone novel Antkind, Kaufman clearly subscribes to this same notion, leading Joel and Anomalisa’s Michael Stone (voice of David Thewlis) through terrain not just populated by their most intimate hang-ups and desires, but sculpted by them.

This pair of films form the key to a deeper appreciation for the sense of culmination that I’m Thinking of Ending Things brings to Kaufman’s oeuvre. The excursion to Jake’s boyhood home fully obliterates the boundary between what’s thought and what’s seen, as we learn in the hallucinatory climax. Without spoonfeeding anyone this information, Kaufman hints that the film up to that point has been a figment in the softening mind of Jake, in actuality an older, embittered janitor working at his old school. For the first time, Kaufman requires no rational (well, semi-rational) textual explanation for our way into a character’s head. While in the car with Jake, the Young Woman notes that everything around them is “tinged,” refracted through their personal impressions. The animated pig that later beckons Jake to his eternal rest enlightens him that “You, me, ideas — we’re all one thing.” Kaufman has pursued these profound truths for decades, and in this zone of untethered nonreality, he can at last grasp them.

2020’s one-two punch of Antkind and I’m Thinking of Ending Things joins in a diptych of sorts, and not just because they both feature sexy clown women. Kaufman spoke in a recent profile about his yearning to transcend the limitations of the cinematic medium, where budgetary, formal and technological limitations put a hard ceiling on what can be considered viable. These companion pieces each provided him with an opportunity to free himself, whether through the pure elasticity of dream or the infinite possibility of the page. He exerts a totality of control over these environments that we’ve never seen from him before. In Antkind, this enables our man B. Rosenberger Rosenberg to have sexual intercourse with a sentient mountain range in the middle of the United States; in I’m Thinking of Ending Things, it allows for the stunning dance number that clues us in to the specific nature of the core writerly ploy.

Though the customary depressive cloud still hangs over his fretful output, he’s never appeared so artistically liberated. At the Chicago Humanities Festival, he reportedly mentioned that he may tackle a Japanese novel called The Memory Police, which sounds fittingly Kaufmanesque to start with. Still, it’s tempting to look at this year not just as a fitting endpoint to his career, but as a completion. He’s devised one bizarre method after another to simulate turmoil and turpitude with greater emotional precision than real life can permit. In disposing with his explanations — in letting the fake be fake, knowing that its artifice leads to truth — he’s made a breakthrough to a new phase of postmodern poignancy. He’d been strafing the ridges of the brain, mapping its contours. Now he’s inside, with a fresh universe of potential to explore. For Kaufman, that’s surely cause for stress, as is the prospect of beginning any new undertaking. For those of us lucky enough to reap the products of his nervous brilliance, however, nothing could be more thrilling.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.