Film critics like to take pride in clairvoyance. The ability to watch an unknown actor in a breakout performance and instantly call a lifetime of fame and success — like Babe Ruth pointing his bat past the outfield in self-assured prophecy — is the easiest way to prove that we know a star when we see one. In recent weeks, I’ve spoken with a handful of peers who also remember playing Tinseltown executive upon seeing Lakeith Stanfield’s big-screen debut in 2013’s indie drama Short Term 12 (then credited as “Keith”), chomping our imaginary cigars and growling, “That kid’s got a future in this business!” The number of my colleagues who arrived at this same conclusion does have a diminishing effect on the prescience of our insights, though. He made it too easy to tell he’d be huge.

In the eight years since he stood out as a troubled teen poet preparing to leave his group home, Stanfield has risen to the top of the heap as predicted, asserting himself as the most consistent, adventurous and talented actor of his generation. He’s been a topic of conversation over the past month due to his superb work as the lead of Judas and the Black Messiah, due on HBO Max this Friday. As William O’Neal, the turncoat FBI informant among the ranks of the Fred Hampton-led Black Panther Party, the actor puts all his finest virtues on full display: his versatility, his empathy, his fearlessness, his gentle intensity, his unmatched skill in silent facial emoting. He’s operating at a caliber of excellence that many professionals labor their entire lives to attain. Most of them would count themselves blessed to have one such triumph in their lifelong C.V., but for Stanfield, it’s the highest peak yet in a career that keeps going onward and upward. He’s a bona fide movie star at a time when those have grown scarce, and more exciting still, he’s defied every mold of celebrity offered to him.

It’s an age-old manager’s adage that unknowns coming up would do well to model themselves on someone identifiable. A “Tom Cruise type” knows that he’s masculine, clean-cut and put-together in a rough-and-tumble way, just as a “Julia Roberts type” knows that she’s the approachable everygal with a big personality and a bigger laugh. Every choice Stanfield makes seems geared to resist that strategy and stave off possible points of comparison. Going by exemplars of Black male fame, he’s not alpha enough to be a Denzel, animated enough to be an Eddie or slick enough to be a Will Smith. He can do funny, but he’s too subdued to be comic relief. He can do romance, but he’s too offbeat to be the heartthrob. As a dialed-back utility player with the gravitas to command the screen and lead studio projects, the only person he really reminds me of is Philip Seymour Hoffman, which also happens to be the highest compliment I can pay another human being.

While that difficult-to-pigeonhole quality has spelt doom for countless others, in Stanfield’s case, it’s brought him a smorgasbord of work united by his unpredictable, shifting charisma. In some early instances, his eclectic interests have trickled down into his pick of gigs, as when his stated passion for anime compelled him to be the most compelling part of the otherwise unremarkable live-action Death Note adaptation at Netflix. An appreciation of jazz and hip-hop prepared him to play Miles Davis’s invented protege in Don Cheadle’s biopic Miles Ahead and a late-‘80s Snoop Dogg in the N.W.A. dramatization Straight Outta Compton. In channeling the young D-O-double-G, he wisely refrained from imitating the genuine article’s distinctive voice or look, balking at the conspicuous and artificial in favor of the organic and understated. Before long, this would become his M.O.

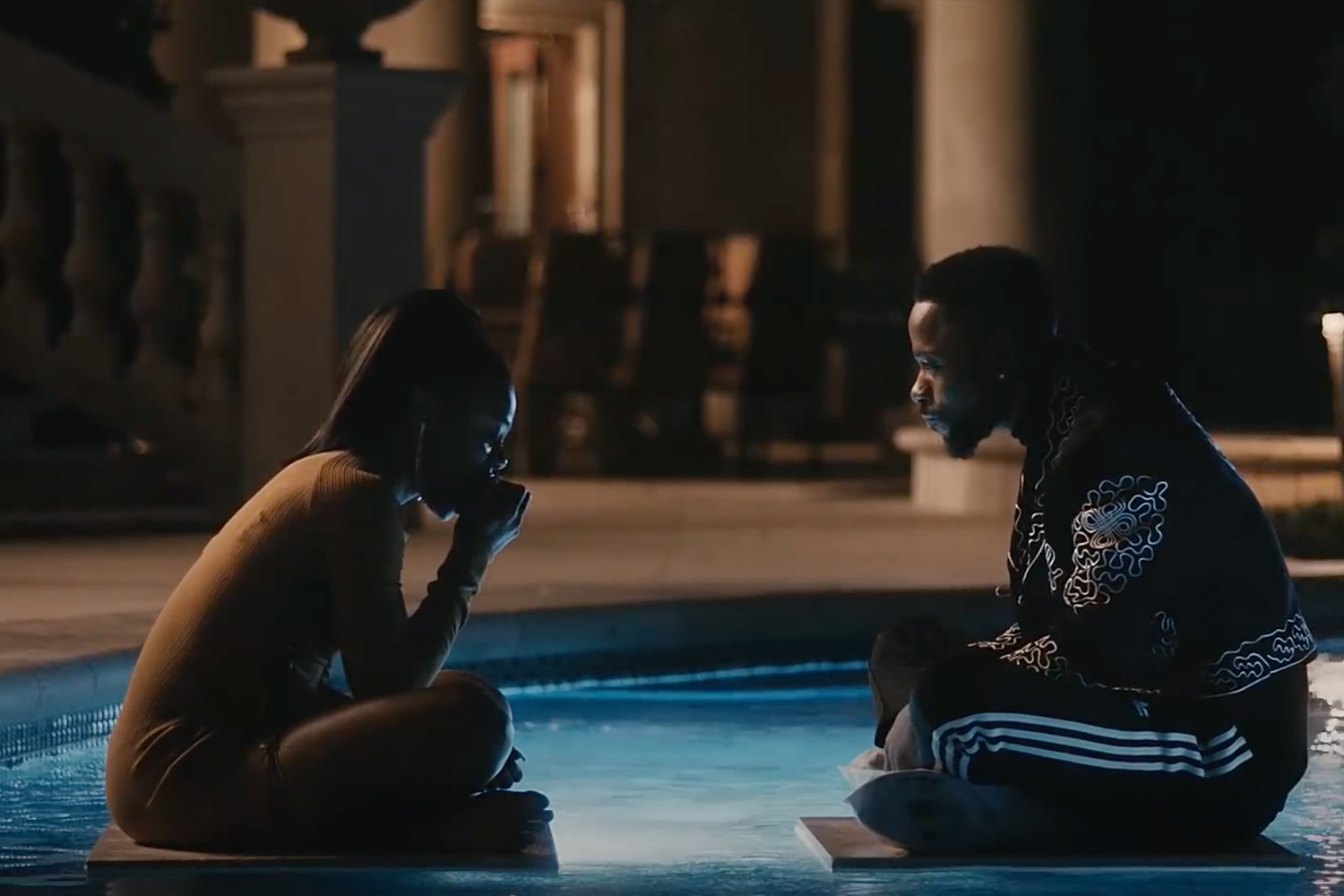

Those roles both came in 2015, the last year in which Stanfield could still feasibly be touted as a well-kept secret. He ascended to the next echelon upon joining the cast of FX’s Atlanta in 2016, this time as shamanic rap consigliere Darius, an instant fan-favorite and the ideal vessel for the actor’s idiosyncratic methods. Stanfield’s knack for deadpan humor and his deep aloofness (or is it an aloof depth?) meshed perfectly with a character a shade more profound than your average stoner-philosopher. In one of his most memorable scenes, he calms a girl a little too high by walking her through simulation theory as they sit poolside at Drake’s house. The professorial way Stanfield enunciates “immense computing power,” his lilting cadence — everything is arranged just right to turn a potential mansplanation into an intimate sharing of perspectives between two hearts, even if one’s too zonked to process it. In his other crowning achievement, he breaks the tension at an unsettling coke buy from the members of Migos by muttering, “Well, it’s a drug deal, so it’s … total vibes.”

Casting agents stood up and took notice, and Stanfield seemingly seized every opportunity available to him. He had a few prolific years in which he tackled an Oliver Stone movie (Snowden), a Sundance darling (Crown Heights), a military satire with all the big-budget trimmings (War Machine) and a memorable bit part in an instant horror classic (Get Out). To play Andre, the first victim caught in Jordan Peele’s web of caucasian deception, he was tasked with telegraphing unspeakable terror through his eyes while his body remains under the control of a sinister white hypnotist. There’s a direct line to be traced between his shattered gaze in that film and the thousand-yard stare of O’Neal in Judas, two men buckling under the immense weight of their internal conflict.

The lighter entries to his C.V. would evince an ability to balance commercial appeal with judicious arthouse curiosity. The pair of Netflix romcoms The Incredible Jessica James and Someone Great posited him as the ex who got away, soulful and sensitive and laid-back about his own handsomeness. 2020’s The Photograph allowed him to more fully embrace his romantic-lead bona fides, courting Issa Rae in a stripped-down film that exists for little purpose other than to let us watch two attractive, likable people fall in love. His comedies, however, err away from the mainstream. He stood in as himself to play sidekick in history’s most chaotic talk show on the last season of Eric Andre, though he reached more viewers as the linchpin holding together the surrealist capitalism satire Sorry to Bother You. To even take the role of telemarketer-turned-titan-of-industry Cassius Green required a measure of daring from Stanfield, a gamble he made pay off through the game attitude he brought to doing “white voice” and turning into a horse-mutant.

He can vacillate between those left-field jobs and more-or-less regular guys, such as Demany, the hot-tempered hustler from Uncut Gems, or Elliot, the right-hand detective to Daniel Craig’s chicken-fried gumshoe in Knives Out. He also deliberately enacted an image of status quo normalcy as the Black replacement for Chandler in the Friends-spoofing music video for Jay-Z’s single “Moonlight.” His better-than-usual ratio of hits to misses speaks to a discerning view of cinema, an artistic temperament that appears to be undergirded by inner torment he’s hinted at in evasive, Dylan-esque interviews and cryptic, alarming social media posts.

Everything has led Stanfield to Judas and the Black Messiah, a herculean challenge with as much visibility as an American release can hope to get. Daniel Kaluuya gives the flashier performance as firebrand revolutionary Fred Hampton, but Stanfield takes a subtler, more complicated tack. He has to, with O’Neal defined more by gnawing guilt than hot-burning rage. He goes rat for the feds out of obliged self-preservation, having been pinched for stealing cars and impersonating an officer. The pit in his stomach starts to shrink as he gets a little too comfortable in a routine with regular rewards, relaying info about meal programs and meeting times to little evident consequence. It’s not until the FBI cracks down harder that O’Neal realizes just how badly he’s messed up and how few options he has left. Stanfield eschews all histrionics for a slower mount from scene to scene, as his own moral bankruptcy fully dawns on him. Look into his eyes and you can almost see his soul leaving his body.

Stanfield holds the audience’s compassion for a contemptible coward, and more astonishing still, quietly relinquishes it as he gives up on salvaging himself. It’s a display of naked, uncompromised humanity, someone accepting their mistakes with only the thinnest veneer of denial about how low they’ve sunk. Actors obsessed with likability wouldn’t touch O’Neal with a 10-foot pole, but he fits right in to Stanfield’s repertoire, because pretty much anyone can. He’s every bit as chameleonic as the heavyweight thespians who love wigs and weight gain, except that his flexibility is in demeanor rather than appearance. With little more a heavy-lidded look, he can convey yearning, shame or exasperation. He inspires hyperbole that can stand up to scrutiny; no one in his Hollywood class is as intriguing a personality off the screen, or as reliably captivating a presence on it. If there’s any justice left in this world, the next decade will belong to him.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.