Dr. Christine Blasey Ford appeared in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday to testify about her accusation that Judge Brett Kavanaugh, President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, sexually assaulted her when they were in high school.

Ford claims that the assault happened during one summer in the early 1980s, when she was 15 and Kavanaugh was 17.

Kavanaugh testified following Ford’s questioning on the assault allegations.

As Congress — and the nation — debate the accusations and testimony, one of the common defenses of Kavanaugh is that “boys will be boys.” Indeed, Kavanaugh’s alleged behavior does not happen in a vacuum.

This “boys will be boys” mentality is deeply embedded in American culture, especially shown through the movies of the 1970s and 1980s, when the alleged assault on Ford took place. Kavanaugh himself mentioned Animal House (1978), Caddyshack (1980), and Fast Times (1982) during his own testimony on Thursday.

Kavanaugh calls his high school yearbook “A DISASTER.” He says the editors wanted it to be a mix of Animal House, Caddyshack and Fast Times at Ridgemont High. “This past week my friends and I have cringed when we read about it and talk to each other,” Kavanaugh says thru tears.

— James Hohmann (@jameshohmann) September 27, 2018

The raunchy teen comedies of the time, including the ones Kavanaugh mentions, explicitly condone and promote sexual misconduct by treating it as a joke. These films played a role in the public perception and societal acceptance of sexual assault at the time and in the future, leading all the way to the present.

The movies Kavanaugh mentioned (Fast Times At Ridgemont High, Animal House) all depict serious rape culture

— Alexandra Svokos (@asvokos) September 27, 2018

This is your brain on cinema

According to The Atlantic, 1985 “marked the zenith for films aimed at younger audiences, across genres ranging from action-adventure to sci-fi to fantasy.” In 1985, people aged 12 to 24 were the biggest group of moviegoers. According to Tara Swart, a neuroscientist and senior lecturer at MIT, your brain’s wiring is most malleable during your “terrible twos” and your teen years. This suggests that many of those teens seeing the movies could learn behaviors from what they were witnessing on the big screen.

National Lampoon’s Animal House, the 1978 comedy about a group of boys who are members of a fraternity in college provided quite an eduction. There is a scene where John “Bluto” Blutarsky (John Belushi) climbs a ladder to watch a group of sorority women through the window as they have a half-naked pillow fight. Then there’s the scene where freshmen Pinto (Tom Hulce) debates whether or not he should have sex with his unconscious date. The punchline later in the movie is that the girl is only 13-years-old.

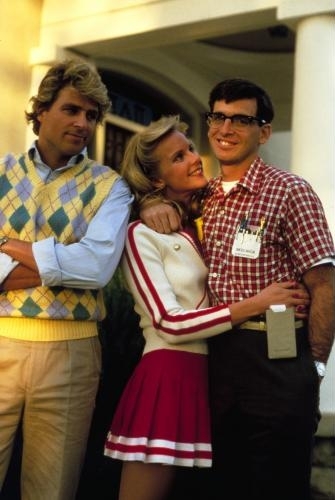

More lessons came in Revenge of the Nerds, released in 1984, about geeky college students who plot their revenge against fraternity members after the frat kicks them out of the dorm. In the movie, one of the “geeks,” Lewis Skolnick (Robert Carradine), steals jock Stan Gable’s (Ted McGinley) costume so that Stan’s girlfriend Betty (Julia Montgomery) will have sex with him. But don’t worry — the deception is okay because Lewis is “good at sex.” Betty later says that she loves Lewis.

This scene occurs after all the “nerds” sell nude photos of Betty, taken without her consent, to raise money for their fraternity.

And we cannot forget the Molly Ringwald classics, The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles.

In The Breakfast Club, a movie by John Hughes about a hodgepodge group of teenagers bonding during detention, the bad-boy character John Bender (Judd Nelson) ducks under the table to hide from a teacher. Ringwald’s character, Claire, is sitting at the table, and John takes the opportunity to look up Claire’s skirt. Though the audience does not see it, it is implied that John touches Claire inappropriately.

Ringwald herself took to The New Yorker to talk about that scene.

“If attitudes toward female subjugation are systemic, and I believe that they are, it stands to reason that the art we consume and sanction plays some part in reinforcing those same attitudes,” the actress wrote.

She goes on to say that she can “see now” that Bender sexually harasses Claire throughout the film.

“When he’s not sexualizing her, he takes out his rage on her with vicious contempt, calling her “pathetic,” mocking her as “Queenie.” It’s rejection that inspires his vitriol,” Ringwald said.

To understand rape culture and acceptance, watch any John Hughes 80s teens movie. For that matter, a bunch of 80s teens movies.

— Natalie Y Moore (@natalieymoore) September 27, 2018

Another Ringwald and Hughes movie, Sixteen Candles, has multiple instances of sexual misconduct. For starters, the 1984 film, which follows Ringwald’s character Samantha Baker on the day of her 16th birthday (which everyone forgets), glamorizes non-consensual sex. After a wild party, the romantic hero Jake (Michael Schoeffling) doesn’t feel like dealing with his very drunk girlfriend, Caroline (Haviland Morris), though he does say, “I could violate her 10 different ways if I wanted to.”

Instead, he hands her off to a young, sober boy, Ted (Anthony Michael Hall). Jake tells Ted and his friends to “have fun with her.” Later, we find out that Ted and Caroline had sex, but Caroline doesn’t remember it. The Huffington Post writes that today, this would be called date rape. Ted and drunk Caroline also pose for photos before they have sex, when Caroline’s underwear and her bra are exposed.

In The New Yorker, Ringwald writes about her new outlook on the films:

“If I sound overly critical, it’s only with hindsight. Back then, I was only vaguely aware of how inappropriate much of John’s writing was, given my limited experience and what was considered normal at the time. I was well into my thirties before I stopped considering verbally abusive men more interesting than the nice ones. ”

The list goes on and on

The list of rape culture in 80s movies doesn’t stop there. In Back to the Future, released in 1985, Marty’s mom is attacked at the school dance. The school bully does not take no as an answer, and viewers see an attempted rape in his car. This is all done so Marty’s dad can be seen as a hero.

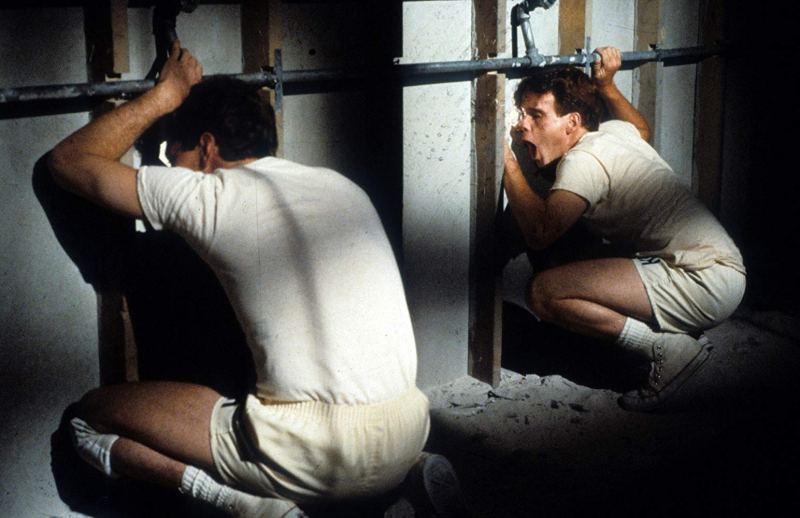

And of course there’s Porky’s, released in 1981, which is filled with unapologetic objectification. The movie is about six boys who go to a strip club to try to hire a prostitute to take the virginity of one of their group members. One of the most famous scenes of the movie is when the boys drill a hole into the girls’ locker room in order to spy on them in the shower. At one point, one of the characters put his penis through the hole.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg (Ghostbusters, Say Anything and Big, for example, all have instances of sexual misconduct as well). Across the board, the sexual misconduct, even the rape scenes, described in the movies above, are treated with a very lighthearted and jovial approach.

As the world reckons with the #MeToo movement and the fall of powerful men like Harvey Weinstein and Leslie Moonves, and as the Kavanaugh hearings rock social media, society also needs to review past lessons that inform our beliefs about behaviors today. Though deeply ingrained, the notions that “Boys will be boys” and “That’s just locker room talk” are no longer acceptable excuses for sexual misconduct.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.