As of late, it has gotten increasingly hard to deny that we’re all going to hell — you, me, America, Earth. The human species has done a number on the planet, pillaging its natural resources and befouling its atmosphere past the point of no return, setting us all on a path that ends in inevitable destruction on a cosmic scale. Before that happens, we’ll keep busy by killing ourselves, violent imperial forces bringing war to more readily exploited nations. If this is the way of the world, it only seems so because those on the winning side of capitalism have a lot invested in maintaining this suicidal status quo, under which the rich get unfathomably richer while the poor are left to die. Some filmmakers have evinced an awareness of this much, Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia adopting a duly apocalyptic attitude, but Paul Schrader’s the only one who really feels it in his bones.

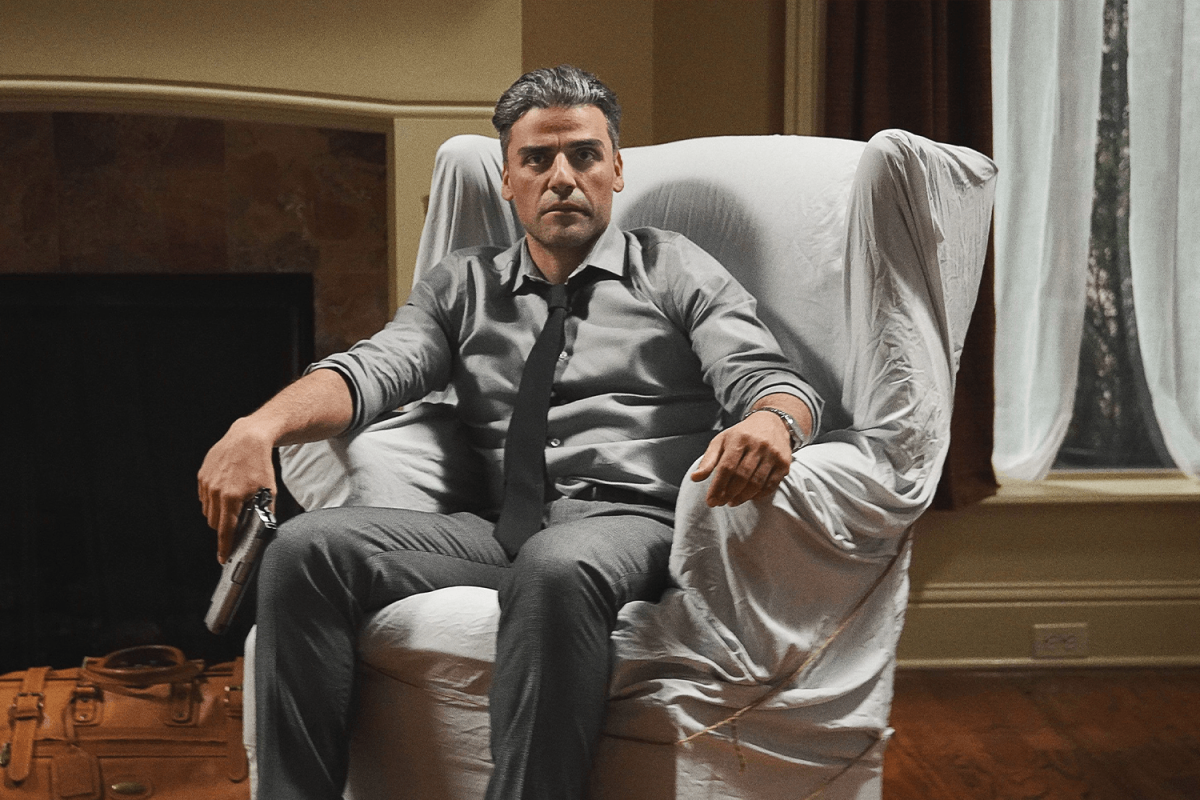

With a fidelity verging on the religious, his new film The Card Counter continues many of the preoccupations and motifs running through his nearly five-decade career as screenwriter and director. We’ve got a haunted, intense man (Oscar Isaac, as great as he’s ever been in the role of ex-con poker shark William Tell) who’s traversed the underbelly of society and felt nothing but sickened by what he’s found. There’s a possibility of redemption in the younger generation, his attempt to save a junior companion’s soul (Tye Sheridan, filling the narrative space held by teen sex worker Jodie Foster in the Schrader-penned Taxi Driver) our last hope at preserving some future for ourselves. And there’s an explosive climax dusted with gunpowder and flecked with blood. But The Card Counter and its clear companion picture First Reformed bring a bracing newfound hopelessness to the filmmaker’s hardcore pessimism, doubling down on damnation. He’s become the American cinema’s preeminent prophet of doom, unflinchingly honest about how far beyond salvation we really are.

The film slots William Tell neatly into the cycle of sin and penance that’s given shape to Schrader’s entire filmography while keeping him close to Christian-in-arms Martin Scorsese, an executive producer on The Card Counter. Rather than sharing in the ornate grandeur hewing to Scorsese’s Catholic roots, however, the restless Calvinist-turned-Episcopalian-turned-Presbyterian instead embraces a thoroughly Protestant asceticism in both his characters and style. Like any servant of God worth his salts, William Tell spends every minute of every day wracked with a guilt he devotes his entire self to assuaging; his sense of willful deprivation is so strong that upon entering each grubby hotel room he makes his temporary home, his first order of business is wrapping everything in a nullifying white cloth. Celibate and chaste, the occasional drink is his only vice, though the whiskey he slugs while journaling (a habit shared by our man Reverend Ernst Toller in First Reformed) suggests a function closer to numbing self-punishment than cutting loose.

He’s done some reprehensible shit, and he’s willing to own that much. In flashbacks shot through an extreme fisheye lens bending the edges of the frame for a hallucinatory effect, we see that he was on the cutting edge of human rights abuses during the heyday of “enhanced interrogation” at Abu Ghraib. Like the notorious Lynndie England, he lands himself in prison not for his crimes but for their photo documentation, while those responsible for worse enjoy a retirement of speaking gigs at industry conventions. After a stint in the clink during which William gets in some good atoning (instead of flagellating himself, he provokes a fellow inmate into smashing his face), he runs into one such monster who got away scot-free. He encounters his former commanding officer Major John Gordo (Willem Dafoe) at the same time he meets Cirk (Sheridan), a young extremist bent on killing Gordo for hanging the kid’s father out to dry just like William once the Congressional probes set in. And with that, we’ve got ourselves a sturdy moral quandary.

William shrugs off his self-imposed isolation to set Cirk on the way of the righteous, teaching him the card-table skills required to get by and pay off some of his mounting debts. In his way, Will preaches a gospel of forgiveness, urging Cirk to forge onward and leave his grudges in the past instead of nurturing them to destroy him. The question of whether we can meaningfully reform ourselves is central to Schrader’s whole body of work, and the answer invariably turns out to be no. This time around, the stakes have national-to-global implications, as transgressions committed overseas come back to destabilize America, the true guilty party. Just as William has uncoiled enough to let himself share in a scorching sex scene with business partner LaLinda (Tiffany Haddish, playing against type to marvelous success), everything comes undone and lives are senselessly lost. Will’s involvement lands him back in jail, now looking more like a purgatory, where the film leaves his fate unresolved but not looking so rosy.

William’s effort to maintain a quiet neutrality in his life — he never bilks enough in his gambling to arouse the casino’s ire, just enough to get by — and its terrible disruption mirror the circumstances faced by man of the cloth Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) in Schrader’s previous film. He also carries an unbearable burden, his son a casualty in the American occupation of Iraq, and is likewise jolted into action via a millennial led astray by radical ideas. The environmentalism advocate Michael (Phillip Ettinger) puts the predicament we all share in sobering terms when Toller comes to give him spiritual counsel, warning that the end of the world is no longer a remote concept. It’s coming, it’s already here, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

It won’t be long until God’s judging us for all the ruin we’ve wrought on his beauteous creation. What will we have to say for ourselves? Toller faces a choice between holy war (the bomb vest confiscated from Michael is pure temptation) and pacifism, clinging to whatever grace remains in this compromised existence. He makes the right decision, but like William, too late. We’re all complicit in the impending heat-death of our habitat, and only those willing to throw themselves at the mercy of the Almighty stand an uncertain chance of surviving his judgement. Both First Reformed and The Card Counter conclude on an ambiguous note, our detached antiheroes having made a sincere connection that nonetheless may not be enough to cleanse their souls. “Waves are going to come up and get you all day every day,” Schrader said by way of explanatory metaphor in a recent interview. “They’re going to try to batter you. Let them. The waves will go away. You’ll still be there. Don’t compete. In the end, the rocks will win.”

In focusing on a climate change fatalist unable to cope with nature itself withering before his very eyes, a description transferred from the helpless Michael to his shattered custodian Toller, First Reformed opened a new chapter in Schrader’s oeuvre that The Card Counter further develops. His output earlier in the decade had been inconsistent, fixated on turpitude seemingly for its own sake. The sleek lecherousness of The Canyons and the griminess of Dog Eat Dog supplied the degradation and filth Schrader knows how to lament, but we’ve only just begun to see the light flickering on and off in the next plane. His comeback duology rises to a higher purpose by daring to suggest that absolution may be feasible, but we’re probably in too deep to reach it. By accepting this, his last couple films attain a reassuring calm despite their forecast of condemnation. The thought that there’s nothing left to be done is soothing and alarming in equal measure.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.