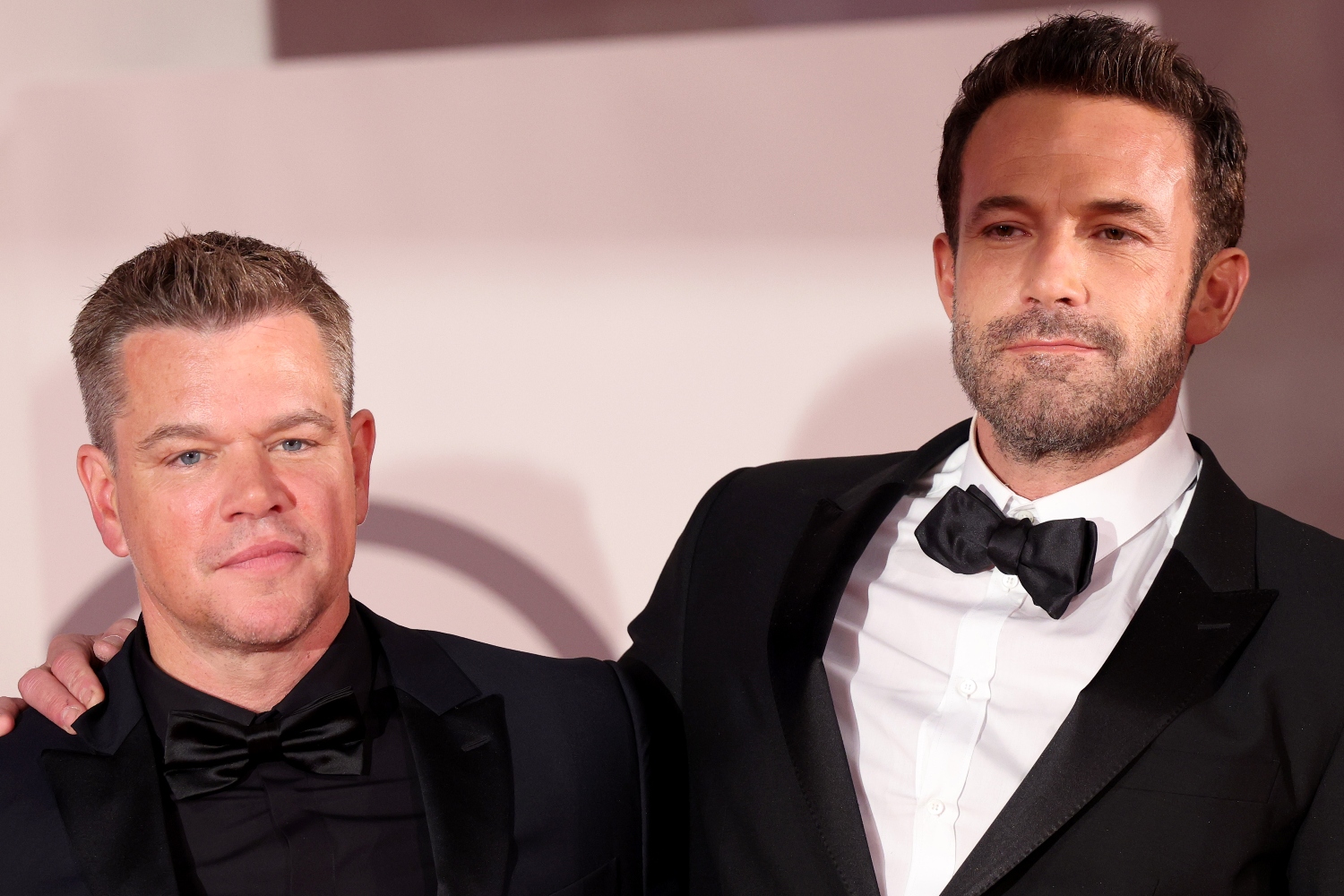

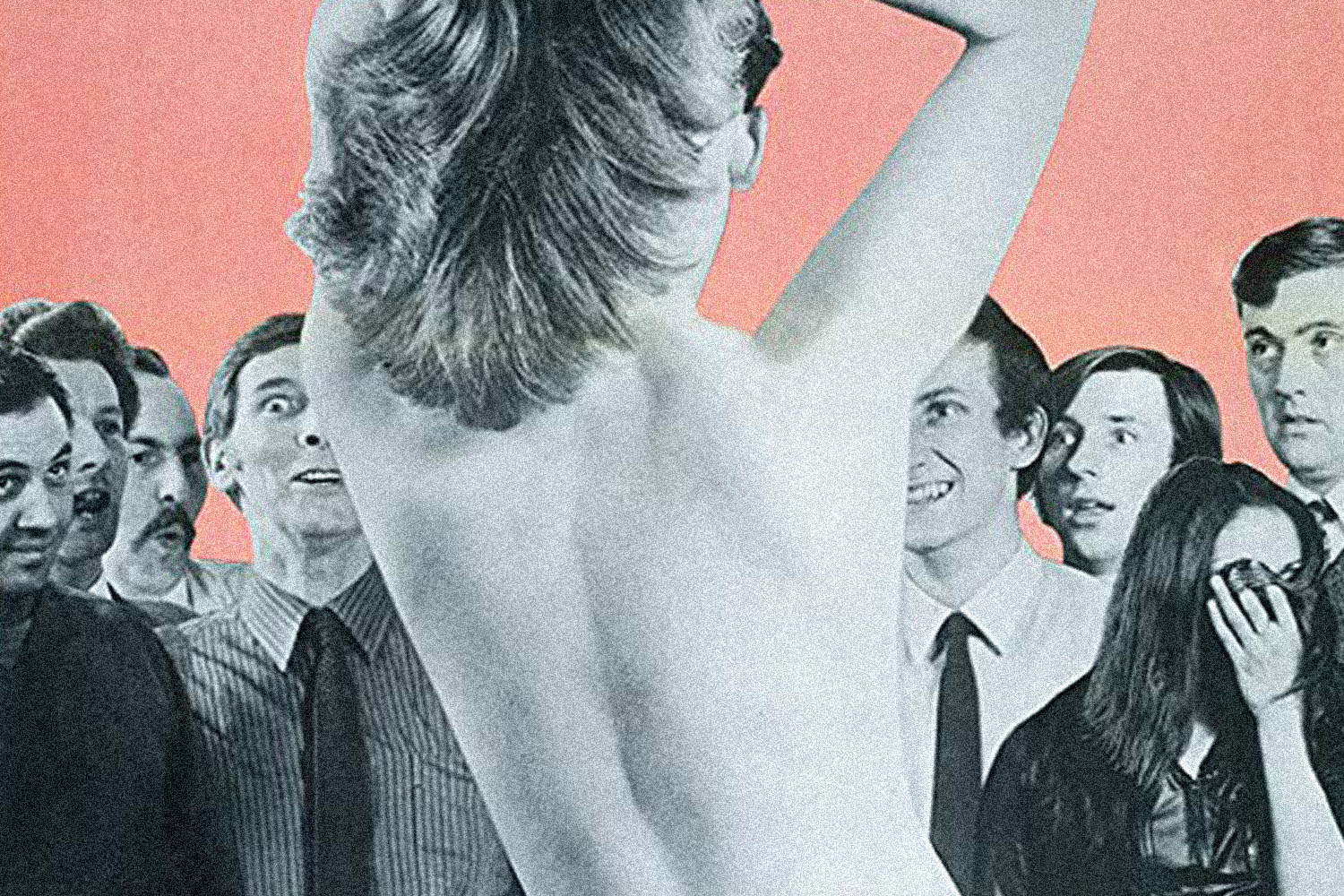

Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas like it when we watch. With the lights of Broadway dimmed during summer 2020, the then-paramours innovated the most vital form of public theater to come out of the pandemic in their frequent, well-documented canoodles. Any afternoon could bring another gem from their “pap walks” exemplifying the uneasy symbiosis between celebrities and the tabloid media that they can sometimes use for image control. The PR-savvy among us could smell the calculations behind the look-how-great-we’re-doing displays of affection; getting matching heart necklaces, for instance, is something high-schoolers do to prove their love is no teen infatuation. However performative the many snapshots of de Armas making her best “oh, Ben, you’re so funny!” face might seem, they can’t help revealing the truth that these two people are keenly aware of being seen. A guy doesn’t plop a cardboard cutout of his new girlfriend on his front lawn, then have it stuffed in the garbage post-breakup, without considering the situation’s optics.

As Vulture’s Alison Willmore broke down in an insightful essay last fall, the closest thing the hard-to-classify Affleck has to a persona is that of gossip-rag fascination object. The same could pretty much be said of de Armas, who’ll play fellow obsessed-over sex symbol Marilyn Monroe in Blonde later this year. Their joint turn in the new Deep Water — the long-delayed, little-publicized, nonetheless excellent campaign to revive the out-of-vogue erotic thriller — puts this dimension to cannier use than ever. Affleck and de Armas didn’t couple up until after wrapping the film in early 2020, and the deal for director Adrian Lyne to adapt Patricia Highsmith’s novel had been in development limbo since 2013. But even incidentally, this felicitous pairing of actors and project improves both, pushing the pair to a scalding white heat while reestablishing the appeal that once made the genre a reliable box-office phenom. Like the psychosexual sparring partners in the film Vic and Melinda Van Allen, it’s a twisted match made in heaven.

It’s been 20 years since Lyne’s last movie, in part because we don’t really make his kind of movies anymore. Back in 1987, Fatal Attraction was the highest-grossing worldwide release of the year and racked up six Academy Award nominations, then the hundred-million-dollar grosses of Indecent Proposal and Unfaithful demonstrated that this popularity wasn’t a fluke. These slinky, kinky games of lust and revenge saw top-flight movie stars working every ounce of their charisma to pull off the mix of earnest turn-ons and scare-quoted humor, and in the most successful cases, critics and viewers got the bit. Despite this, something in the air sent the erotic thriller out of favor after the new millennium. (My theory, often articulated at high decibels for weary bar patrons, ascribes the shift to America’s transition from the randy scandalousness of the Clinton years to the conservative culture-warring under Dubya.) Lyne now returns to a chastened Hollywood, its private parts caged by the militant sexlessness of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its franchised ilk.

In this respect, Deep Water feels as refreshing as its title suggests. At a time when schoolmarms on both sides of the ideological aisle have a vested interest in combing through onscreen couplings for anything improper — do yourself a favor and never google “Licorice Pizza + age gap” — the playful sadism of the Van Allens is as risky as it is frisky. The script joins Vic and Melinda with a pall of suspicion already cast over them, her open-secret boytoy having recently gone missing. Occam’s razor says the husband did it, and though Vic denies his culpability to his side-eyeing social circle, he likes lording Melinda’s uncertainty over her. She calls him “Mister Boring” while grinding all over her latest fling at one of the many house parties that fill the young retirees’ evenings. (He invented the computer program used to guide drones, a hint that his disregard for death is easily rationalized away.) Could homicidal urges be lurking behind his insincere smile?

A pattern forms as the plot introduces and hastily dispatches such tall, interchangeable white men as Euphoria’s Jacob Elordi or Ryan Murphy regular Finn Wittrock. Melinda gets her kicks giving these hunks road handjobs or indiscreet closet quickies, but it’s the rubbing it in her husband’s face that really turns her on. Around her, he maintains a facade of shifty indifference, preferring to spend his free time in his greenhouse playing with his beloved pet snails, perhaps relating to their squishiness under the hard shell. (Online factoid repository Mark Asch has explained this odd touch as an idiosyncrasy of Highsmith’s, who had an empathetic bond to her invertebrate darlings.) Though their tension inches toward a boiling point with each successive disappearance, they get one pivotal beat apiece in which they’re made to answer for why they’d stay with someone so keen on torment.

As they come to mutually accept that they’re titillated by all the infidelity and murder, what first appeared to be a dysfunctional pas de deux between doomed lovers takes a turn to the unconventional and tender. In terms that take time to clarify themselves, a stagnant couple renegotiates the parameters of their relationship, in the same crafty template as The Duke of Burgundy’s sapphic BDSM romance or Phantom Thread’s food-poisoning-as-foreplay. Viewed in this light, perverse gestures between them can be redefined as miniature intimacies, as when she allows him to rub lotion on her thighs before banishing him to the garage. Later on, he walks in on her shaving her legs in the bath, preparing herself for that night’s man. It’s not until she faces away from him and the quiet scrape of the razor over her pubic hair becomes audible that we fully grasp what a personal moment they’re sharing.

Tonally, this is a delicate balancing act that demands a surgical handle on levity and seriousness from the actors and director alike. Lyne, he of the bunny-boiling notoriety, knows how to reconcile an accented atmosphere bordering on the ground of camp with being straight-up funny. If the Internet is good for anything, unlikely comic relief Tracy Letts screaming “GODDAMN FUCKING AUTOCORRECT” while texting and driving will be memed to viral immortality. The sexual component is even trickier in its finely calibrated proportions of innuendo to saying it out loud, the criterion by which all erotic thrillers are judged. The suggestive shots of, say, fingers nimbly flying over the keys of a piano may elicit a chuckle with their bawdy implications. Still, the actual sex winked at by dancing or biking is unironically mesmerizing, no matter how far over the top it goes. It’s joking without joking, a paradox executed like it’s second nature by Affleck and de Armas.

To put it modestly, it helps that these actors meant to be long-since-cooled homebodies nonetheless have the crazed chemistry of two people in the process of realizing how badly they want each other. Part of the erotic thriller’s decline has been due to the sad dearth of true-blue movie stars in the current generation, many of the biggest names belonging to the headliner intellectual properties. The performances from Affleck and de Armas lend themselves to old-fashioned precedents, a tarnished showbiz glitz in keeping with the A-list glow added by the meta-intrigue between them. She’s the sort of vamp archetype that’s been all but absent since her heyday in ‘40s film noir, and he’s a subversion of the mope caught in her thrall. As previously affirmed by Gone Girl, essentially a photo-negative gender-flipping the sins, Affleck was born to play an untrustworthy man with an unsavory secret. They’re well-worn molds of character, living and dying with the actors that elevate the dialogue through their magnetic presence.

Nearly a year and a half of postponements may work in Deep Water’s favor after all. In the interim time, the flashy dissolution of the celeb union dubbed “Benana” has invigorated their act as Vic and Melinda. Their discord adds another layer to the spouses with an interior dynamic unknowable to the eyes prying from the outside, yet too mercurial to be covered by the normalcy they can barely be bothered to project. Don’t take it from me, take it from the house-destroying fight scene from Mr. and Mrs. Smith: in the movies, there’s nothing hotter than glimpsing a trace of the real in a playacted attraction between professionally gorgeous people. There’s a greasy little thrill in the inkling that we’re peering in past privacy, turned into voyeurs with our gazes fixed on the forbidden.

Better still, we’re free to do so without shame, reassured by the exhibitionist tendencies of those writhing in the camera’s sights. Through Lyne’s expertise as well as Affleck and de Armas’ gameness about their semi-transparency, the erotic thriller once again attains its highest aspiration by obliterating the concept of the guilty pleasure. That guilt, the sense that we’re doing what we shouldn’t, is the pleasure. Vic and Melinda rekindle the flame by changing their perspective on indulging in the bad to feel good, accepting that maybe it’s okay to be excited by the sleazy things we’re not supposed to. Ultimately, we’re treated to the same privilege.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.