This is the latest installment of the 2022 edition of the French Dispatches, our on-the-ground coverage of the Cannes Film Festival. Watch this space over the next fortnight for more from the 75th edition.

Baz Luhrmann’s single overarching insight into pop culture is that, throughout history, it is all exactly the same. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is the Buzz Bin; the Paris of the Belle Epoque is Now That’s What I Call Music; the Jazz Age is Roc-A-Fella. And so, now, at last, Cannes welcomes Elvis (here in France, where I am, we call it “Elveez”). Elvis, about an artist whose galvanic contribution to the American Century was his synthesis of white and Black music, of hillbilly twang and bluesy strut, is rendered in the usual Luhrmann way, with bedazzled production design and cutting that everyone calls “MTV-style” despite the fact the Luhrmann has never been a music video director and it shows. The film, whose screenplay is credited to five writers including Luhrmann twice (with two different writing partners; he also has a story credit with the other credited writer) rifles through the King’s well-known biography for pop parallels. Since Elvis once mentioned reading comic books, Luhrmann repeatedly imagines him as a caped superhero; the soundtrack is full of anachronistic electric arrangements and modern covers of Elvis songs by the likes of Kacey Musgraves and Doja Cat.

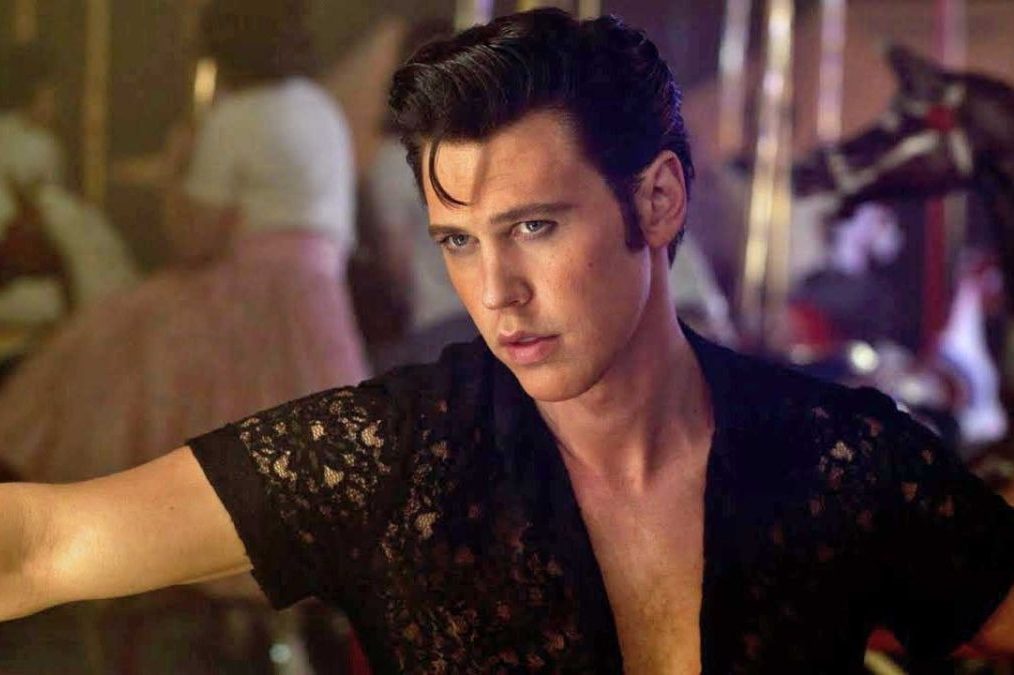

Luhrmann, perhaps preemptively concerned about cultural-appropriation discourse, also brings Elvis into the endless present in other ways. He gives us a Woke Elvis, humbly worshipful of Black musicians and conscious of the Civil Rights struggles, in an exaggerated and pointedly repeated dramatization of the complex interchange between white and Black musicians in the early days of rock, and of Elvis’s well-documented respect for Black stars such as Jackie Wilson and social conscience. (The movie even sends us out on “In the Ghetto.”) When Elvis’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), first hears “That’s All Right, Mama” and finds out that the singer is white, Luhrmann dollies in on Hanks’s face so you can see the dollar signs spinning in his eyes. “He’s white!” Parker marvels. (Luhrmann simplifies and triple-underlines everything.) In his childhood, Elvis sneaks over to the Black side of town to watch raunchy blues through the window, just like the young protagonist in Great Balls of Fire!, the 1989 biopic of Elvis’s Sun Records labelmate Jerry Lee Lewis, and gets the spirit at a Black tent revival. Gospel and blues, with its refrains of “I’ll fly away” and “Sometime I feel like a motherless child,” do much of the script’s heavy thematic lifting. There’s maybe a suspicion here that the Memphis blues, as with the jazz and hip-hop in The Great Gatsby, is serving primarily to decorate the story of a white artist and give it palatable modern sheen. For a movie as long as Elvis (nearly two and three-quarter hours), there’s not a ton of his music, with mostly partial performances of his biggest hits. (This is especially noteworthy at a Cannes where I also saw Ethan Coen’s new archival documentary about Jerry Lee Lewis, in which numerous full performances give a sense of the Killer’s stage presence and the crosscurrents of influence feeding into the various stages of his career.) In an impossible role, Austin Butler does well with Elvis’s flirty, sneering baritone voice and the hillbilly kung-fu of his stage moves.

This the whole story of Elvis’s life, more or less, with major figures and iconic quirks and anecdotes stuffed like package padding into Luhrmann’s constant swirl of activity. Everyone’s hair changes with the times and supporting characters are constantly announcing who they are. It’s very Walk Hard in a way that I’m convinced is at least a little intentional: Surely a crewmember laughed when Elvis, declining an invitation from the gospel great Mahalia Jackson, politely demurs by saying, “Sorry, Ms. Jackson.”

Elvis’s interactions with society at large seem to mostly consist of watching, and reacting to, televised coverage of various assassinations. There’s little, in particular, about his relationship between him and his public, beyond the early scene of a crowd going absolutely b-a-n-a-n-a-s for his dance moves and well-worn story of TV refusing to broadcast his lascivious pelvis; anything related to post-WWII mass media and generational change — and later the burgeoning nostalgia industry, one of the most transformative arcs of Elvis’s legacy — is smoothed over by Luhrmann, who is only interested in Fame as a timeless constant spiritual striving uncolored by any particulars. When the camera passes so swiftly over so many richly textured surfaces, spangled with CGI text and split-screens, there’s no time to slow down, so the entertainment business is mostly rendered in the old music-biopic character arc of his three-act relationship with Colonel Parker, the first larger-than-life top-skimming rock-manager.

Parker brought Elvis to Las Vegas, where the movie starts, ends and spends the most time, and which clearly interests Luhrmann as the spiritual home of American dreaming and spectacle. There, where the slot machines whir and the amphetamines flow, the film depicts Elvis as a holy innocent corrupted by fame, losing his equilibrium and his marriage to Priscilla Presley (Olivia DeJonge). (Elvis met Priscilla when she was 14, and before their marriage she lived with him secretly at Graceland while still a high school student. Priscilla Presley is still alive, and walked the red carpet with the film’s cast on Wednesday night; watching the movie, you can tell.) In Vegas, soaking up the adulation of crowds even as they become more isolated from the world, Elvis and Colonel Tom Parker are always reaching, reaching for that… green light. No, the green light was Gatsby. Here it’s called something else. Everything is always exactly the same to Luhrmann, only the costumes change, from pink prom suits to jumpsuits.

I cannot emphasize enough that this is a stupid movie, aesthetically, historically and narratively. To the extent that it engages with the history of American popular music and race, it’s a disastrous rehashing of lazy and inadequate shorthand conventional wisdom. As goofy spectacle, or even as an embodiment of a blingy striving at the heart of the American character, well, the real problem with Luhrmann’s historical-equivalency project is in its execution, not the concept: throwing excess at the screen is no excuse for transporting lyricism. What saves Elvis from being as lousy and enervating as Gatsby is that it does have a genuine camp throughline, a sense of exquisite misconception at once delightful and almost poignant in its wrongness, in Tom Hanks’s performance as the Holland-born Colonel Parker. In Cloud Atlas prosthetics and doing a Goldmember accent, always dandling an elephant-head cane and drawling on about the carnival as a metaphor for American life, Hanks gives a truly disastrous performance, ill-served by a comically abrupt frame story and instantly meme-able. And it’s exactly what Elvis needs.

I alluded in my last dispatch to the consensus that this has been a disappointing Cannes, and now after this, perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it’s been a backloaded one — too late to change anyone’s mind, the Competition snapped into focus in its last few days. Previous Cannes favorite Hirokazu Kore-eda and Lukas Dhont may have reset the jury’s thinking with their Thursday premieres. Kore-eda won the Palme d’Or in 2018 for Shoplifters, and Broker, based on the Korean phenomenon of the “Baby Box,” a place to anonymously deposit unwanted infants, is another tender story about found families on the margins of society. Belgian director Dhont won the Camera d’Or, for best first film, in 2018 for the coming-of-age film Girl, which was widely and rightly critically savaged for its representation of a trans story. A lot of people wanted, sight unseen, to hate Dhont’s Competition debut Close, but it won many of them over, with another preciously poised queer-coded teen drama, about two boys whose lose childhood friendship is challenged, quite traumatically, by the shifting terrain of adolescence. Both films are very emotionally accessible, and anchored by fine performances, from, respectively, Parasite lead and Korean megastar Song Kang-ho and K-Pop idol Lee Ji-uen (who makes music as IU) in Broker, and Close newcomers Eden Dambrine and Gustav de Waele.

Claire Denis, one of the greatest living artists in any medium, also had a late competition entry, with Stars at Noon, which absolutely bombed. The thing about Cannes is that a lot of people who are not film critics — entertainment reporters, industry hangers-on — come to world premieres and shape discourse around a film. A lot of people know Denis by reputation but have no particular affinity for her work, which can lead to a disastrous response for a film which is a tough sit at times but resonates fascinatingly with her whole body of work. Stars at Noon, adapted from Denis Johnson’s flawed but fascinating ’80s novel about the U.S. presence in Nicaragua, is by no means her most perfectly realized work — a very smart friend told me he thought it was conceivably her worst film. To which I could only respond: “… okay? So?”

Starring a surprising and vivid Margaret Qualley in a steely, girlish performance and a strategically vague Joe Alwyn, Stars at Noon is about an American woman and British man who fall into bed together in conflict-rife Nicaragua and then go on the run together, if initially only as far as her motel bed, when they fall afoul of various vague security forces. Shot in shaky, broody widescreen in disorientingly anonymous parts of Panama, with a beautiful score by Denis regular Tindersticks, the film has echoes of previous iconic films of hers, particularly the sensual reverie Friday Night (starring Palme d’Or jury president Vincent Lindon), and her many musings on colonialism — Qualley particularly recalls Isabelle Huppert’s hard-edged mania and careless arrogance in White Material. Updating Johnson’s ’80s novel to the COVID-19 era, Denis shows her characters clumsily navigating world made newly unwieldy and viscous, encountering new masking rituals and temperature checks — unfamiliar points of contact between the self and the world, for this most tactile of filmmakers.

Denis follows the book’s plot too closely — I found myself wishing I hadn’t read it, I think even more confusion over the plot would have been productive — but she and her cinematographer Eric Gautier are able to evoke a physical sense of the world better than Johnson, who funnels his incredible poetic language through a poorly conceived first-person narrator, a caustic slut clearly influenced by Joan Didion, who had just written Salvador. Qualley gets the recklessness and intelligence of that voice, which feels like a more natural fit in Denis’s world than Johnson’s. She also has incredible hair, massive and kinky, like her mom Andie MacDowell, and it expands like creeping moss in the jungle heat. This is a humid film, with Qualley and Alwyn’s wet sticky torsos and everyone’s sweat, and this, more than Johnson’s dubious, personalized politics and descriptions of Nicaragua as “hell,” gives impression of a white subjectivity overwhelmed by an environment it can’t control.

I’m seeing my last competition film, Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up, starring Michelle Williams as a sculptor, immediately after filing this. Advance word is strong. With the awards ceremony on Saturday night, no one really knows what will happen. See you next week.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.