W. David Marx writes in his book Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style that in the first decade of the 21st century, American men were discovering, studying and then consuming clothes in a way that “uncannily resembled Japan in 1964.” Maybe you were a denim head versed in the three Ws (warp, weft, weight), a goth-rocker who could layer the Viridi-Anne, Number (N)ine and Undercover with the best of them, or an Ivy classicist with a J. Press collection worthy of a Men’s Club spread. Until Marx’s book was published, menswear aficionados had not articulated the resolutely postmodern way that Ametora brands — the Japanese slang term for “American Traditional” style — studied, replicated and reinterpreted the Oxford cloth button-downs, flat-front straight-leg chinos and prepped-up blazers for an emerging youth culture in postwar Japan.

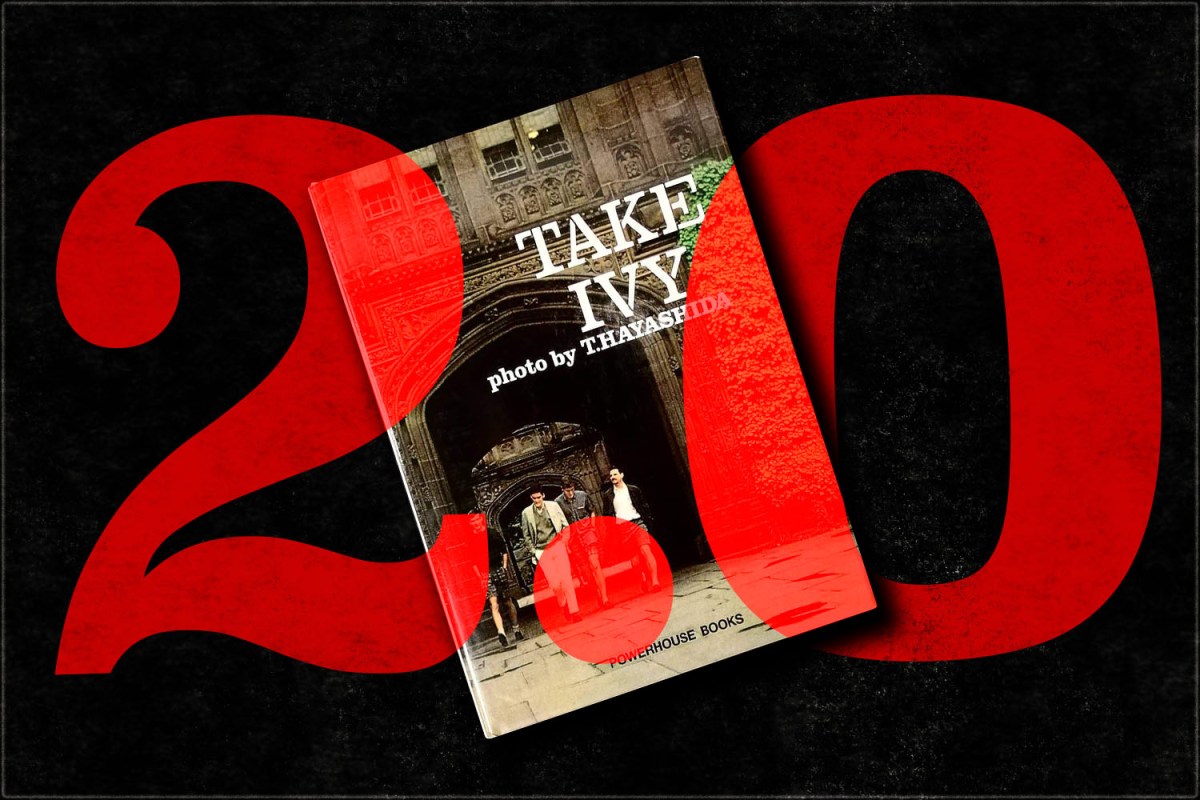

Eventually, the particular ethos we now know as “Made in Japan” was exported back to the heirs of its origins. With a few exceptions, this three-word sentence on thousands of pieces of product copy signals an authenticity that, for some, still surpasses homegrown wares, which challenges a base sentimentalism in the American mind. But the success of Japanese brands that are part of the Take Ivy Effect (named after the 1965 Japanese fashion photography book) proves that authenticity does not necessarily have to mean native-born.

In the days before social media and online retail merged, we only had forums and Google Translate as our guides. Many of us mistakenly believed that the regimens of cold soaks and ocean scrubs we evaluated on discussion threads were really how most Japanese took care of their denim. When asked about this phenomenon in Marx’s book, Kiya Babzani, founder of Selfedge, explained it like this: “If you ask Japanese brands how they take care of their jeans, they kind of look at you in a funny way: We just wash them … in the washing machine.”

It’s as if the polarities of the Take Ivy impact — the Japanese exportation of Ametora and its subsequent consumption by a legion of American men crafting new narratives to express masculinity — were starting to reverse in the early parts of the century. Our laundry anxieties mirrored the way mid-century Japanese teens fussed over Ivy styles when we worried whether or not a Levi’s Vintage Clothing Type 2 repro was a period-correct pairing with a pair of Samurai 710xx.

But as Take Ivy Americanized and grew beyond the realm of specialists thanks to upmarket offerings from J. Crew, as hundreds of one-man brands set up shop on Instagram for their own authentic jeans, the Japanese were eschewing period-correct aesthetics, minimizing 501s and jean jackets to mere fit descriptions like “straight leg” and “two-pocket jacket.” Attention spans changed. Streetwear came to dominate both the retail and resale markets, leaving the #workwear tag in the cobwebbed corners of the pre-2017 Instagram algorithm. But even that trend might see its end sooner than later: “I would definitely say [streetwear’s] gonna die, you know? Like, its time will be up. In my mind, how many more t-shirts can we own, how many more hoodies, how many sneakers,” Virgil Abloh recently told DAZED.

If streetwear is on its way out, and Heritage has been dead for a few years now, what’s next? It’s Take Ivy 2.0.

According to Marx, Take Ivy 1.0 operated within a paradigm of “‘copying towards innovation.’” Artisans must first master the kata, or “single authoritative ‘form,’” before they break and eventually separate from the source. Known as shu-ha-ri (protecting, breaking, separating), the most exciting Japanese brands today are those that deviate from historical accuracy in favor of an uncanny balance of old and new, such as Auralee, Phlannel or Comoli. When it comes to elevated basics in the current menswear landscape, newcomers to the world of men’s fashion have few options: opt for either a subdued normcore uniform inaugurated by the likes of Steve Jobs and George Costanza or a slim-tapered jean with some work boots. I’m over-simplifying, of course, but what I’m calling Take Ivy 2.0 are the far more enticing tastemakers in the retail scene who think beyond those conventions. Taking the lessons of Take Ivy 1.0 to heart, these brands have fully adopted the shu-ha-ri ethos towards the U.S. sportswear archive.

It’s no surprise, then, that an American Take Ivy 2.0 brand would find success abroad before the States, and one such operation is Lady White Co., an L.A.-based outfit that first focused on white jersey T-shirts but has since expanded to minimalist tweaks and re-interpretations of sweatshirts, button-down polos, sweats, and soon, coats. Helmed by Phil Proyce and a tight-knit crew, his wife Sarah Benea and best friend Taylor Caruso among them, the line’s initial run of vintage-inspired T-shirts found initial success with Japanese shops focused on heritage reproductions and upmarket, minimalist basics. Notable among its first range of international stockists was 1LDK, which has shops in central Tokyo and abroad in Seoul and Paris.

When Proyce started Lady White, its ethos was clear to those versed in the culture of Take Ivy: Do one thing, and do it very, very well. The culture of shu-ha-ri was evident even when they only offered two things: a white and a black T-shirt. Proyce sees the T-shirt as the American essential, a form that has not changed significantly in its nearly century-long history. Eventually, the brand ventured into long sleeves, sweatshirts and other fundamental forms of American sportswear. The cotton for all of these products is knit, cut and sewn within a five-mile radius of its recently opened flagship location in Silverlake.

That’s where I meet Proyce to talk over his approach to designing what he calls his “most honest view of USA sportswear,” and it’s the first thing I’m curious about. Inside the shop, you won’t find exposed wood or floors, no leather couches, and no motorcycles. Instead, you’ll step onto bland gray carpet assembled from square tiles that are snapped together, no doubt purchased from a catalog, and definitely mass-produced. Rectangular beams suspended from steel rods function as racks, and folded shirts, pants and accessories sit atop light grey display tables made from sturdy plastic. The idea for the shop came from photographs taken of Japanese offices and schools, Proyce explains, and what appealed about these kinds of spaces was how anti-gallery they were — and anti-heritage, I would add. Lady White’s flagship store is orderly, even a little sterile. “I just feel like I made a home for my clothes,” he says.

He pauses our conversation to take a phone call about spring deliveries, and I notice on the wall behind us the brand’s slogan: “USA Sportswear,” replete with the familiar trademark symbol superscript in the upper right hand corner. I flip through a book of Alec Soth’s photography: portraits of Midwesterners posing during a community dance; motel towels molded to mimic two swans kissing; an ordinary but somehow captivating motel sign. Above us are exposed wooden rafters that have been painted over in white. They perhaps once lent a home-y ambience to the space, but now, with the fluorescent lights installed, they cast an austere, almost hygienic light on the racks of clothing. As Proyce gets off the phone, I noticed something off about the logo on the wall. The trademark symbol is inverted.

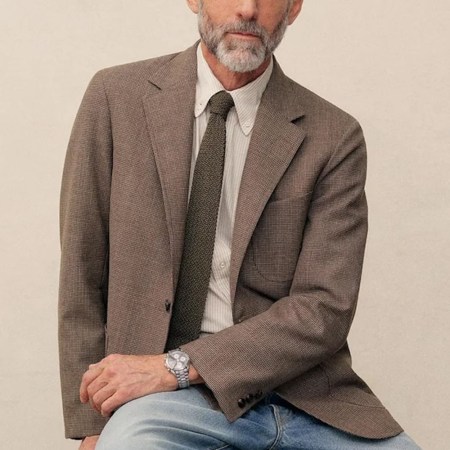

Proyce explains that the brand started to take shape as his time at Rising Sun started to close, around the peak of the heritage craze, just as J. Crew’s Wallace & Barnes and Ralph Lauren’s vintage-focused RRL were migrating out from the sinuous paths of menswear forums and blogs into the mainstream. He wanted Lady White Co. to veer from the idealism embedded in, say, Ralph Lauren’s vision of American sportswear, with its celebration of American leisure and wealth. For Lady White, Period-correct details are eschewed, but the quality we revere in historical garments is pursued. Patterns aren’t made in ways that highlight broad shoulders or favor muscular chests; instead, most of the shoulders sit off the shoulder, inviting, perhaps requiring, to be worn a bit oversized. Notably, Proyce regularly checks the needles at the factory that cuts and sews his clothing.

In an interview with one of Lady White’s U.K. stockists, Oi Polloi, Proyce explains that most of his customers weren’t wearing his clothes for actual sports. “The sport is wearing the clothes.” I ask him to expand on that. His youth spent skating was also a time when he developed his personal style: If you were going to be featured in a video, you also had to look good. Style and sport merged here, and if style is the sport, Lady White’s particular game is having fun getting dressed in their stuff.

This makes sense. The ‘10s were a decade defined by viral fashion and an attendant, perhaps toxic, dependence on validation from an anonymous, algorithmically gathered audience, but it was also a time when fashion was democratized. These converged to increase the pressure for both women and men to have a personal “aesthetic,” which might then be curated into a specific “brand,” which might then be monetized. In that particularly capitalist way, subcultures become normalized and mainstreamed. Your aesthetic is your sport: you might be a thrifter, a sneakerhead, a Supremacist.

With Lady White, Proyce partly measures the success of the brand by whether a customer finds himself (or herself) reaching for a T-shirt or a button-down polo unconsciously, or when a customer explains how they’d saved for one of their ever-popular hoodies. Designed with comfort and the “utmost wear” in mind, Lady White’s clothes are indeed endlessly wearable, mixable and — importantly — comfortable. But it also shouldn’t fit or look like a uniform. I can personally attest to this, having left the house in almost head-to-toe Lady White pieces, but also feeling anonymous. No one else would know that I was wearing a whole kit by one brand — only I would.

Lady White’s customer might be someone who knows nothing about menswear forums or the various identities one can take. They can also be a well-versed enthusiast. Nevertheless, both have something to learn, either in a new silhouette, fit or uncanny color for a T-shirt, like “Fontana Red” or “Victoria Blue.” The shop’s helpful staff, often one of Proyce’s friends, will take you through the details to consider for what you might otherwise see as an ordinary sweatshirt. And online, their product copy pages don’t make spiritual affirmations of American work ethic or spirit — they simply explain how the fabric was made, and how it might feel on your skin. But while they might look ordinary, wearing them highlights their specialties.

Looking at the product photos, you might be simply reminded of your parents’ sweatpants. That wouldn’t be exactly wrong. Being reminded of the banal, humdrum-ness of a pair of pull-on pants is part of the point. The clothes resemble the aesthetic of the Alec Soth book I was looking at. Proyce brings over one by another favorite photographer of his, Takashi Homma, and points out the photographs that inspired custom dyes like “Fontana Red” or “Victoria Blue.” I notice Homma highlights urban infrastructure that we take for granted or ignore, encouraging us to attend to what we don’t see in the pace of daily life: water towers, the center beam of a window frame, the straight line of suburban houses in a tract. In these ways, as LensCulture has described Soth (and it applies as much to Homma), scenes that might be unphotographable are witnessed and even celebrated for their ordinariness, thereby enabling the viewer to witness the “sad beauties of everyday mundanity.”

Proyce’s talent for noticing and elevating the mundane in sportswear staples is exemplary of Take Ivy 2.0. Whereas the first iteration sought and still seeks to re-emphasize ideal images of American sportswear (your RRLs, for example), Take Ivy 2.0 focuses on presenting a different kind of archive of American casualwear. If a pair of pants reminds you of your grandparents (or parents) about ready to melt from their poly-cotton blend tracksuits, why is that necessarily a bad thing? Or the reliably nerdy look of a dropped-shoulder T-shirt tucked into high-waisted sweatshorts, with white socks pulled all the way up: Why can’t this be stylish? Just as Japanese repro brands followed the methods of shu-ha-ri for denim jackets and trousers, so do brands like Lady White. Archival forms are protected, and even celebrated, but they break and separate from their domestic peers by offering their customers a novel take on familiar forms.

In recent seasons, Proyce has taken more risks with new offerings. This fall, for example, the brand debuted its first range of garments made from imported fabrics — the “LA Raglan” is cut in three melange colors with wool from Italy, then sewn in Los Angeles. The “Zip Fleece jacket” is also made from Italian fabric, a high-pile fleece, and the Track Trouser is cut from cloth made in Japan. This spring, Lady White will revisit some old favorites and experiment with tweaked idioms: A high-neck, boxy fitting T-shirt with a mini-striped pattern and contrasting neckline reminiscent of ’60s leisure shirts, and a zipped cardigan that borrows details from coach and baseball jackets. I also got to peek at the AW20 range that both Proyce and Taylor Caruso brought to the Paris exhibitions: more heavyweight sweatshirts, indeed, but also a duffel coat that combines the brand’s custom interlock and heavyweight French terry. “It’s like 10 pounds,” Proyce says.

All of these ventures strike me as one of the foremost expressions of inverting the Take Ivy Effect. It’s not only that Lady White’s clothes have a “sense of old and new,” as their biography describes, but also familiar and strange. Like in Homma and Soth’s photographs, we can identify the scene, and even the form of the scene, but it might take a moment — or longer — to notice which detail Proyce wants us to see. It might be in the fabric, or the ironic tweaks in the cut of a sweatshirt, deliberately made slouchy and loose in a fabric some heritage brands would die for, but the brand’s identity is clear. This isn’t heritage; it’s not even authentic, whatever that means. But it’s honest. It’s what Proyce sees in how sportswear classics should be worn for today. It’s a vision that’s ironic but avoids cynicism, one that modestly elevates and even applauds what most would overlook: the laidback leisure in your uncle’s dropped shoulder in an old family photograph, the embarrassing confidence of a sweatpant in public.

If heritage is dead and streetwear is now awaiting its death throes, then let the mourning be swift.

This article was featured in the InsideHook LA newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Southland.