This is the first installment of a two-part series on cyberbullying at American universities. You can read the second installment, on the return of anonymous messaging app Yik Yak, here.

I. Patient Zero

Monica Lewinksy was not the first woman to have an affair with a president. But other than Marilyn Monroe, can you name another?

There are reasons Lewinsky was singled out by the forces that shape our cultural history. Political opponents of the man with whom she was smitten as a 22-year-old intern seized an opportunity to exploit her. The media played along, making her the poster girl for an endless stream of smut on which the public happily feasted.

But it was the fact that the scandal coincided with the dawn of the digital age that made it so explosive.

“It was the first time the traditional news was usurped by the internet for a major news story,” Lewinsky said in her 2015 TED Talk. “What that meant for me personally was that overnight I went from being a completely private figure to a publicly humiliated one worldwide. I was patient zero of losing a personal reputation on a global scale almost instantaneously.”

In the near quarter-century that has passed since Monica Lewinsky became a household name, the cyberbullying pandemic has not subsided. The virality of hate has only been weaponized more efficiently by the advancement of social media platforms and their seductive power to indulge our worst behavior.

The prevalence of cyberbullying has fueled a heightened awareness of its causes and symptoms. But knowledge without meaningful action only makes a problem more endemic. As the Wall Street Journal reported in their recent “Facebook Files,” the corporation now known as Meta has chosen to ignore internal research that shows the damaging effects its products have on young people. Melania Trump’s advocacy of cyberbullying prevention represents another feeble and histrionic response to a pressing issue. There are, however, many sincere and effective initiatives currently underway to eradicate cyberbullying. Monica Lewinsky has emerged as a compelling and heroic activist, the patient zero who survived.

Social media platforms that champion one’s ability to anonymously exercise First Amendment rights, regardless of noble or idealistic intentions, have exhumed a fact we like to ignore: of the roughly 8.7 million known species on this planet, none match the human’s capacity for cruelty. That may sound misanthropic. But you don’t reach the top of the food chain by being nice.

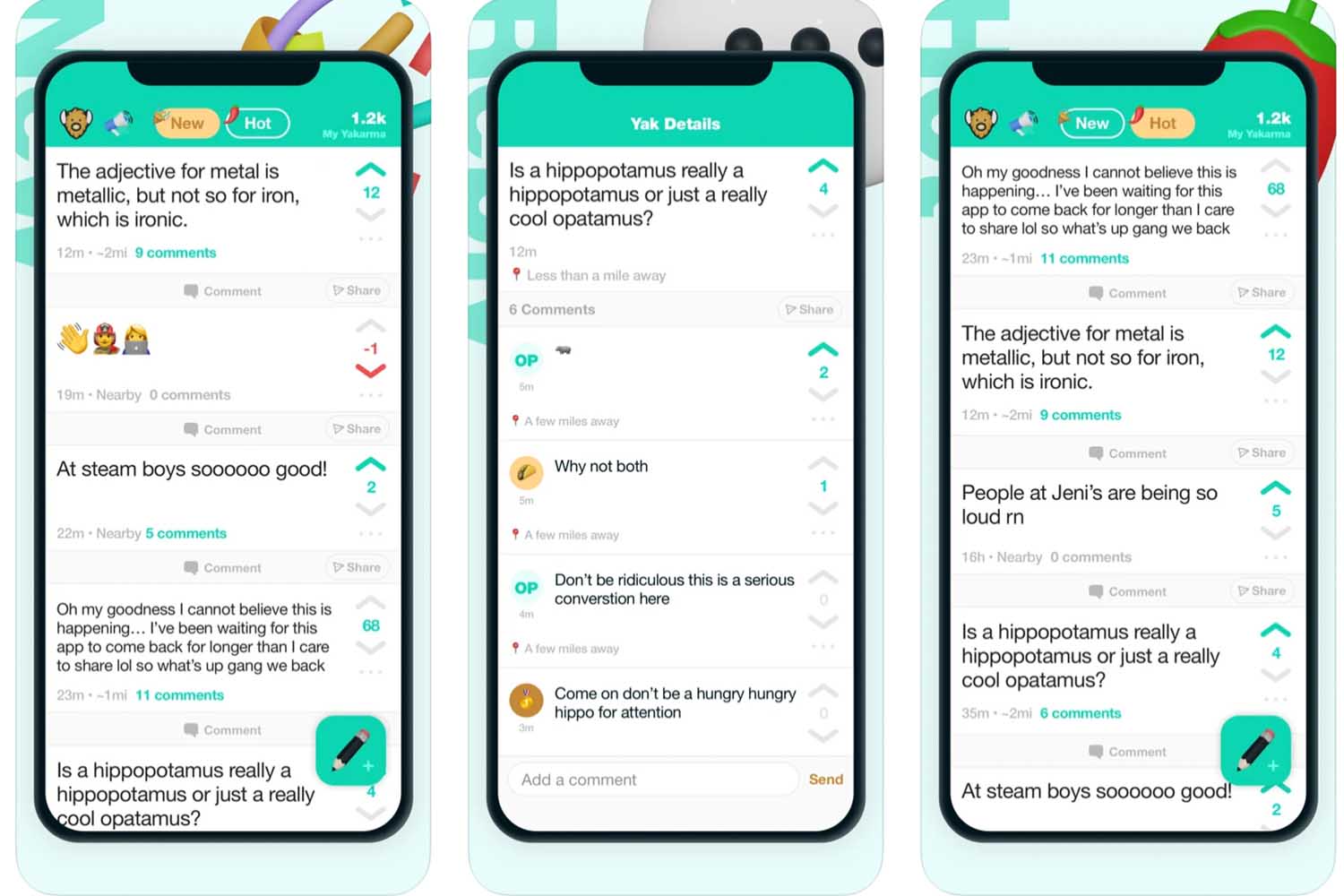

You’ve probably heard of some of these anonymous platforms. Yik Yak, which recently returned to college campuses after a four-year hiatus, is one of the more notorious. But there’s one erstwhile platform you’ve never heard of that might have been the bellwether for all of this.

II. The Dawn of Juicy Campus

Matt Ivester graduated from Duke in 2005 with a degree in economics and computer science. Smart, talented and ambitious, he was set to follow in Mark Zuckerberg’s footsteps as a Millennial wunderkind. As he racked his brain for the next billion-dollar-idea, he kept reminiscing about his time at Duke, where he was president of the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity.

“Even two years out of college some of my favorite stories were from my college days – –just the stupid things my friends and I would do,” Ivester told ABC in 2008. “It occurred to me that every day, on every college campus, every group of friends had these same great stories. So, why not create a place online where people could come together and share those stories?”

In 2007, Ivester launched the website Juicy Campus. Its interface and functionality were sparse and primitive — essentially a threaded discussion board — but its impact on college zeitgeist and its historical place in the development of our broader internet-driven culture were significant.

The company’s mission — its contribution to that comically trite Silicon Valley ethos of making the world a better place — was simply to enable “online anonymous free speech on college campuses.” In reality, and arguably from its very conception, Juicy Campus was nothing more than TMZ or Perez Hilton on a campus-wide scale. Rather than dishing salacious dirt on celebrities — who all, to some extent, accept the Faustian bargain that comes with fame — the site trafficked in the cruel rumors and divulged secrets of everyday undergrads.

The way Juicy Campus worked is that it hosted pages for individual schools. Users were guaranteed anonymity and encouraged to post the “juiciest gossip” from their campus. When the site launched in October 2007, it featured eight schools, including Duke. Ivester and his youthful team worked their college networks to help drive traffic. Sigma Phi Epsilon came through for their brother as Duke students flocked to the site to recap the highlights of fall rush season.

Its popularity attracted early VC funding, which helped Ivester launch targeted Facebook ads. By January, Juicy Campus had 50 schools. A month later, it hit 100. Growing pains followed as their servers struggled to host the surging traffic.

“As many of you know, being popular can be tough,” a company blog post from February 2008 began. “Every day thousands and thousands more people are discovering JuicyCampus [styling theirs]. There is more juicy gossip on the site than ever before! But as a result of all these visitors, the site has slowed down — our servers can’t handle the juice.”

Five days later they were up and running on a new “ultra fast mega server.” These periodic disruptions would occur for the rest of Juicy Campus’s short life, but they did little to slow the company’s meteoric ascent. Ivester touted this growth period as a testament to the power of the First Amendment. For many students, it was a reign of terror.

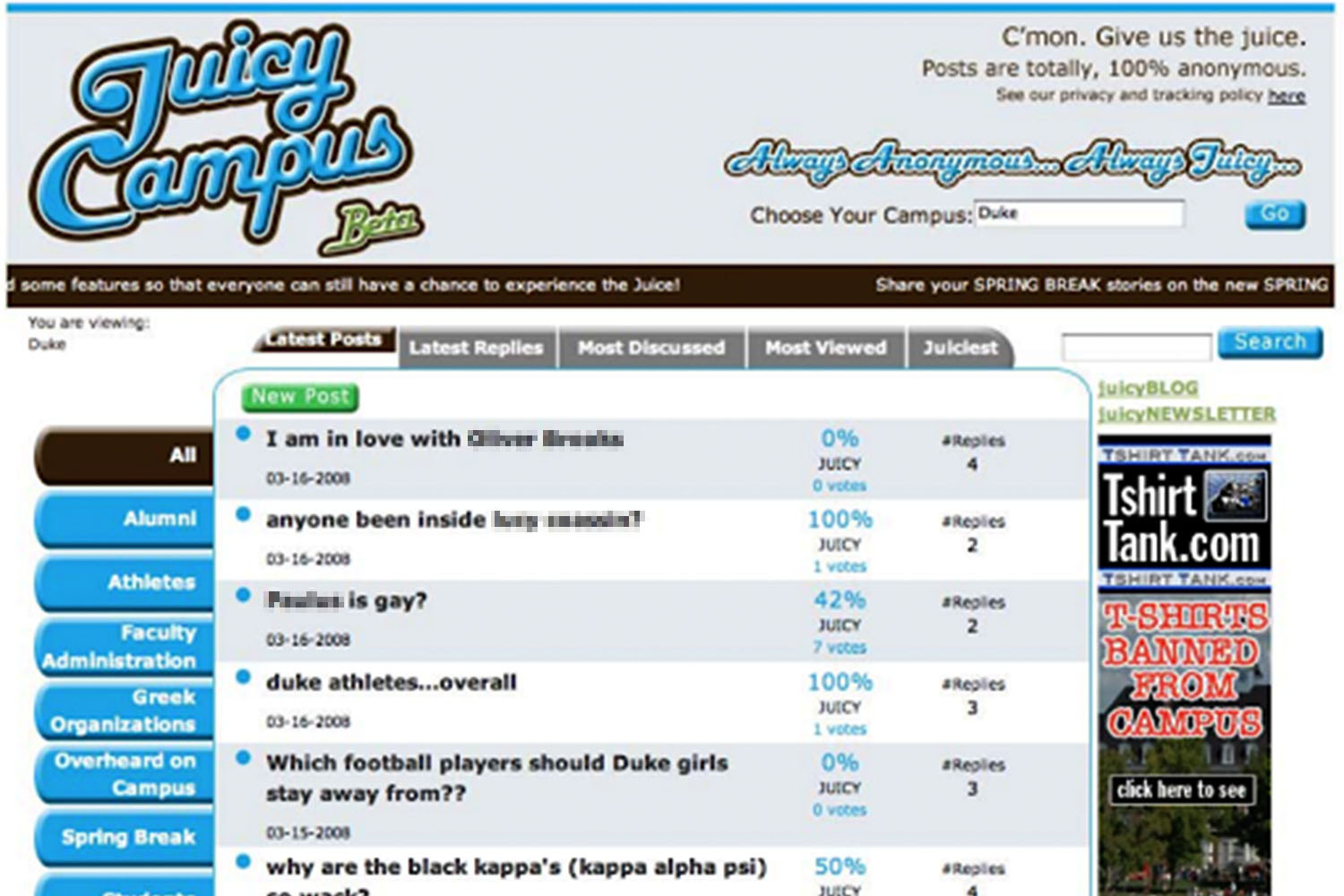

Regardless of the school, every Juicy Campus page devolved to the same content. Popular headlines encouraged users to discuss the “biggest slut on campus” or the “most surprising gay guy” or the “biggest cokehead.” Posts about Greek life and athletic teams were common.

The “juiciest,” most upvoted posts were the ones that named specific students. They traded almost exclusively in highly personal subjects: an individual’s sexual orientation, sexual health, mental health, race, appearance, drug habits. Sometimes they simply stated a person’s name followed ominously by “discuss.”

“The anonymity was a big thing,” a student who attended Georgetown at the time tells InsideHook. “You could just drop a nasty rumor about someone and let it run.”

It was hard to look away.

“My school’s page blew up,” remembers a student who attended WVU Beckley. “[It was] basically a bunch of the Greeks attacking each other. My friends and I had a near daily ritual of gathering for lunch at the school’s cafeteria with our laptops and catching up on the gossip.”

Whether a post had any basis in fact was irrelevant.

“As long as it seemed true, it felt like it suddenly became gospel,” says the Georgetown alum. “If people already believed it or wanted to believe it, it would run. Hence why it was [such a brutal] slut-shaming tool.”

Despite backlash from students and administrators, traffic swelled as school newspapers and the national media reported on Juicy Campus. Many students who were interviewed at the time claimed they never posted on the site but visited regularly because it was entertaining. And they wanted to make sure their name didn’t appear.

Not that they’d be able to do much if it did. The fear of this digital threat — of having zero control over your reputation — was very real. It induced heavy anxiety for many students who were already grappling with the traditional stressors of adolescence. A Baylor junior who was named in her school’s “biggest slut on campus” thread told The New York Times she was worried that potential employers would see the post.

“I’m trying to get a job in business,” she said during a tearful interview. “The last thing I need or want is this kind of maliciousness and lies about me out there on the Internet.”

When asked about this concern, Ivester often pointed out that Juicy Campus blocked search-engine crawlers. While this could prevent an employer (or anyone else) from Googling your name and seeing a Juicy Campus post, nothing could stop them from visiting Juicy Campus and typing your name into the site’s search bar. Furthermore, because Juicy Campus didn’t restrict access to campus pages — for example, users didn’t need to register with a school email address, as was the case with Facebook in its earliest days — anyone could view and comment on any page. Consider this sinister scenario: you’re a college freshman and someone from your high school, maybe a bully or a mean girl, could easily visit your college’s Juicy Campus page and introduce you to your new community.

The toxic content posted by users took a human toll. Students whose names were mentioned in this hyper-local corner of cyberspace were helpless as their neighbors, cloaked by the cold fleece of internet anonymity, commented cruelly or carelessly about their lives.

In 2008, ABC ran a story about a student who was raped by a homeless man during her freshman year at Vanderbilt. When she returned to campus as a sophomore, she was still grappling with the aftershocks of the trauma.

“It was very difficult to go through the routine of going to classes, going to my different activities,” she said. “I had a few panic attacks. I wouldn’t go anywhere by myself after 5, and I sort of felt detached from the rest of my friends, even the ones who knew, because there were some of them that I still hadn’t told about what happened.”

One day a friend called to inform her about a disturbing post on Juicy Campus. She went online and was shattered by a four-word headline: her first and last name followed by “deserved it.”

She clicked into the discussion and read the first anonymous comment. “What could she expect walking around there alone. Everyone thinks she’s so sweet but she got what she deserved. Wish I had been the homeless guy that fucked her.”

Worse than the abhorrent post was the effect it had of turning a private tragedy into public fodder for such a small community.

“That was probably the hardest part — that people would come up and ask me about the post,” she said. “In one case I came up to a group of people that I heard talking about the post, and they had forgotten whose name it was, but they were talking about the post that they had read on Juicy Campus, about somebody who had been raped.”

Like the attack she was trying to recover from, the experience left her feeling powerless.

“It takes the control away again,” she said. “It’s my story to tell, and no one else has the right to tell it. And that something like this was considered gossip is disgusting.”

Although stories like this amplified calls for Juicy Campus to remove the site’s most hurtful posts, Ivester was steadfast in his refusal to moderate content. As inhumane as this seemed, he was backed by an iron-clad legal precedent.

III. Section 230

In 1996, congress passed the Communications Decency Act (CDA). It was a landmark piece of bipartisan legislation, the first overhaul of telecommunications law in more than 60 years. For context, the last time America enacted any kind of laws to regulate communications or public information sharing, morse code was still being used to send telegrams.

Signing the CDA into law, President Clinton trumpeted its importance and acknowledged one of its key architects.

“For nearly two decades, Vice President Gore has worked to spur the creation of a national information superhighway,” he said, a comment that didn’t diminish the widely (if sardonically) circulated legend that Al Gore invented the internet.

“This law is truly revolutionary legislation that will bring the future to our doorstep,” a proud and ruddy-faced Clinton said.

Within a year, the Supreme Court struck down the bulk of the CDA as unconstitutional.

Today, the only reason the CDA remains relevant is because of an obscure provision buried in its middle: Section 230. According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the leading nonprofit for defending civil liberties in the digital world, Section 230 is “the most important law protecting internet speech.” It’s also very controversial.

Having long outlived its parent legislation, Section 230 is the law that states internet platforms are not liable for any third-party content they host. By extension, the platforms have no legal responsibility to moderate or censor any content. To be clear, many of them do engage in moderation, but that’s determined by their individual policies, which have faced heightened regulatory scrutiny in the aftermath of the last two presidential elections.

For different reasons, reforming Section 230 is a priority for lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. The ideological and ethical considerations of the debate exceed the scope of this article, but interested parties should read this comprehensive overview from The Verge. For our purposes, it’s enough to know that every information-sharing platform invokes Section 230 to defend its content moderation policies, whatever they may be. When these companies get taken to court over inflammatory content on their servers, the courts overwhelmingly side with them on the precedent of 230.

IV. Out of Juice

By early 2008, Juicy Campus was fighting a multifront war. Google dealt a blow to the company’s bottomline when it pulled its advertising services. Student associations and school administrators were aligned in their opposition to the website, and there were murmurs of state investigations on the horizon. The national media cranked up the heat.

In late February, Ivester published a blog post titled “Hate isn’t Juicy.”

“Some of the things that have been posted have been mean-spirited, and we have received emails from people claiming to have been defamed on the site,” he wrote. “Our hope for the site has always been that JuicyCampus would be a place for fun, lighthearted gossip, rather than a place to tear down people or groups.”

(Earlier entries on the Juicy Campus blog showed users how to avoid defamation and encrypt their posts to bolster their anonymity).

“Remember that words can hurt, and the people you are talking about are real,” Ivester continued. “Ultimately, JuicyCampus is created by our users, and we ask that you please take this responsibility seriously.”

He ended the post by including “a (boring) note from our lawyers,” which was a vague reminder about the website’s terms and conditions followed by an assertion of its protected legal status:

“Please be advised that Juicy Campus is not the author of the posts that appear on the site. Rather, Juicy Campus is the provider of an interactive computer service. As such, pursuant to 47 U.S.C. Section 230, Juicy Campus is immune from liability arising from content posted by users.”

In March, a Colgate student was arrested after he posted a threat to stage a mass shooting. Authorities quickly learned his identity, which cracked the facade of total anonymity that many users thought they had.

An earlier company blog post had explained where Juicy Campus drew the line in terms of sharing user data.

“If your school calls upset about some girl being called a slut, we’re not handing over access to our server data. If the LAPD calls telling us there is a shooting threat, you better believe we’re gonna help them.”

Bad press continued to flow but did little to curb the company’s growth. In October 2008, Ivester announced their 500th campus.

“Nothing is more American than the right to Freedom of Speech,” he blogged. “We thought it fitting for JuicyCampus’ 500th campus to be one of the most American colleges out there, Gettysburg College.”

Conflating sanctimonious patriotism and entitled defiance, Ivester hammed it up. “Just as Gettysburg was the turning point during the Civil War, we hope Gettysburg will be the turning point where JuicyCampus moves past the resistance put up by campus Administrations and students are free to discuss the topics that interest them most. JuicyCampus is, in Lincoln’s famous words, the website ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people.’”

Here’s what Ivester got wrong: the fiercest resistance to Juicy Campus came not from administrators, but students. It’s understandable why he missed this. For generations, the First Amendment was the hill American college kids were willing to die on. They’d take on any foe, from their school’s leadership to Uncle Sam. But the broad student response to Juicy Campus was different. Using rhetoric that anticipated today’s culture wars, students called for Juicy Campus to be censored.

Student governments passed resolutions to ban the website from campus networks. Wary of the slippery slope that comes with curtailing expression, most school administrators declined to enforce these bans (though some did), but almost all of them issued statements condemning Juicy Campus and putting the onus on the website to moderate offensive content.

“They’re just misguided, and missing the big picture,” Ivester said of college administrators in November 2008. “The most significant threats to free speech (in the U.S. at least) tend to come not from tyrants who openly question the value of the First Amendment, but from well-meaning busybodies who want to protect peoples’ feelings — a mission that is generally incompatible with free speech.”

Two “busybodies” who were alarmed by Juicy Campus were Anne Millgram and Richard Blumenthal, the State Attorneys General for New Jersey and Connecticut. (Millgram is now the head of the DEA and Blumenthal is currently serving his second term in the Senate, where he is spearheading Section 230 reform efforts and learning about finstagram.) Upset by what she was seeing in the news and hearing from constituents, Millgram decided to launch an official investigation into Juicy Campus.

Rather than going after the website for its content, Millgram investigated it for fraud. It was a creative legal strategy, not unlike the government’s decision to pursue Al Capone for tax evasion. Millgram understood that the First Amendment and Section 230 gave Juicy Campus an impenetrable defense against any charges related to its content, but she saw another opening.

Juicy Campus’s terms and conditions stated that users could not post anything “unlawful, threatening, abusive, torturous, defamatory, obscene, libelous or invasive of another person’s privacy.” Millgram argued that the company’s utter lack of any effort or reporting mechanism to enforce these terms could be considered fraudulent.

“Misrepresentation to the public by businesses violates our Consumer Fraud Act,” she said in a press release. “JuicyCampus.com must honor the terms and conditions that it informs the public it will adhere to.”

In Connecticut, Blumenthal charted a similar course.

“I am extremely troubled and disgusted with the assorted, vulgar, hateful, racist and sexist discussion threads, [many of which] serve no purpose other than to besmirch the reputations of college students,” Blumenthal wrote in a letter to Ivester. “The fact that your site so proudly touts the anonymity with which this public degradation occurs is appalling and unacceptable, particularly in light of JuicyCampus’ own Terms and Conditions.”

The investigations in New Jersey and Connecticut carried on for months. Neither one resulted in criminal charges. Maybe they couldn’t find sufficient evidence, or maybe it was because Juicy Campus abruptly shut down in February of 2009.

In his farewell blog post titled “A Juicy Shutdown,” Ivester didn’t mention the investigations. His reasons for closing, he asserted, were purely financial.

“Unfortunately, even with great traffic and strong user loyalty, a business can’t survive and grow without a steady stream of revenue to support it,” he wrote. “In these historically difficult economic times, online ad revenue has plummeted and venture capital funding has dissolved.”

There weren’t many tears shed on Juicy Campus’s behalf. College newspapers across the country quoted cheerful reactions from students and administrators. Even the politicians gloated.

“I’m delighted if our criticism contributed to this insidious site’s collapse,” Blumenthal said in his statement. “JuicyCampus is deservedly dead — out of juice and financially ruined.”

V. A Legacy of Cyberbullying

Juicy Campus vanished, but the seeds it scattered throughout its turbulent life blossomed overnight. Similar websites quickly metastasized across the internet, all of them selling the same juicy idea to drooling VCs: that cyberspace is fertile ground to commodify gossip, and who has more gossip than tech-savvy college kids? Even as nothing more than a decrepit hyperlink, Juicy Campus continued to foment gossip, with the site’s URL redirecting traffic to College ACB (Anonymous Confession Board).

As for Ivester, he landed on his feet. In 2011, he published an anti-cyberbullying book called lol…Omg! and went on to found a few different social media apps, including Kindr, “the world’s first kindness app.” According to his LinkedIn page, he currently works as a product manager at Facebook. InsideHook reached out to him for a comment on this story, but he did not respond.

So why does the rise and fall of a website almost nobody remembers have any relevance today? The quick answer is because platforms that allow anonymous posting with low-to-no moderation continue to be havens for cyberbullies. You can easily draw a line from Juicy Campus to apps such as Yik Yak, like one of those evolutionary illustrations that shows how dinosaurs turned into chickens.

The companies that followed Juicy Campus have adapted to avoid the same legal vulnerabilities — many of them now require users to register with some piece of identifying data like a phone number or email address, and they have stricter policies with built-in reporting for abusive content, e.g. — but they’re still enabling horrible behavior that disportionately affects young people.

Obviously there are many examples that show how anonymous speech can be used for positive outcomes. Anonymity is an important tool journalists use to protect sources from retribution or persecution. It empowers whistleblowers to speak up even when power dynamics are stacked against them. And there are several platforms like Reddit (or at least certain forums therein) that prove anonymous user-moderated content can create healthy digital communities.

The rub is that our blind commitment to an ideal has prevented us from combating a serious problem with meaningful action. But that doesn’t mean a solution will elude us forever. It’s important to remember that our lives are taking place in the prologue of mankind’s relationship with cyberspace. It hasn’t even been 40 years since Al Gore invented the internet. Look at how much the world has changed in that blip.

The optimist will say there’s no reason we can’t figure this out. The cynic will tell you we never had a chance. Centuries from now, our descendants will look back at this era and draw a line that connects our present to theirs. I wonder what they’ll make of it.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.