“Jim Jeffries must now emerge from his Alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you. The White Man must be rescued.”—Jack London, author of Call of the Wild

On May 2, 2015, African-American Floyd Mayweather fought Filipino Manny Pacquiao. At the weigh-in, Mayweather was 146 pounds and Pacquiao 145. Neither had much of a weight cut—Mayweather stands 5’8” and Pacquiao is just over 5’5”.

In the past, boxing wouldn’t have viewed this bout as a particularly big deal. It barely qualified as a title fight. They were contesting the WBO welterweight belt. It’s a championship of such minimal significance that—on a night he collected $200 million—Mayweather chose to forfeit it rather than pay a $200 thousand sanctioning fee. Beyond this, they weren’t heavyweights—both are decidedly below average in size.

And above all, neither man is white.

Historically, how could a promoter get the public excited about something like that?

Yet the bout sold a record 4.6 million PPVs for $89.95 each (or $99.95 for those demanding high-def). And it confirmed what should have long been clear: Boxing has officially moved beyond the myth of the Great White Hope. For decades, the sport was hung up on the notion that—even when things were going well—they’d be better if a white guy could just claim the heavyweight title already.

This is how a racist tradition came about and why it at last fell to pieces.

Bow to the Boston Strong Boy

If you follow boxing, you know it’s diverse in a way few other entertainments are. A glance at Ring Magazine’s Pound for Pound rankings invariably reveals Americans, Mexicans, Ukrainians, Asians from various nations, etc., with a wide mix of races and religions and sizes as well—in this era, a star can emerge from an array of weight classes. The one common thread is that it’s a poor man’s sport. (As the great Sugar Ray Leonard put it, “We can’t afford to play golf or tennis.”)

Which makes it all the stranger that for a century boxing fixated on the image of a white heavyweight champ. The tradition started in the 19th century with John L. Sullivan and lived on through fighters including Jim Jeffries, Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano, and finally Tommy Morrison. Some of these men, products of their time, seemed to genuinely believe they were defenders of their fellow whites. Others were indifferent to race or even uncomfortable with how they were portrayed. Regardless, it was a pathway to some blockbuster bouts and utterly reprehensible rhetoric.

Sullivan is one of boxing’s great transitional figures. Between his 1882 win over Paddy Ryan and his 1892 loss to James J. Corbett, he is generally accepted as being the last bare-knuckle heavyweight champion and the first gloved heavyweight champ of Queensberry rules. In the era before mixed martial arts or pro football, boxers were an easy pick as the toughest athletes around. Since heavyweights are the biggest, they were perceived as the hardiest of all. (Facts are facts: Generally speaking, it pays to pick fights with small guys instead of large ones.) Sullivan exploited this for all it was worth—it’s believed he earned a million dollars during his career.

That was far more than Sullivan could have been expected to generate in any other profession. After all, he was the son of Irish Catholic immigrants. They weren’t a popular group at the time—it would be decades before JFK reached the White House. Sullivan was a hard-drinking man prone to announce, “I can lick any son of a bitch in the house,” and then attempt to back it up. Without boxing, these qualities would have brought him to prison. With it, he was adored and celebrated. “His Fistic Majesty” even became friends with President Theodore Roosevelt.

Of course, “any son of bitch” had an important qualifier. Sullivan declared, “I will not fight a Negro. I never have, and I never shall.” (Though for a time he reportedly considered doing so, provided he was paid twice his normal fee.) His successors also towed the color line. Jim Jeffries even proclaimed, “When there are no white men left to fight, I will quit the business.” He kept his word, retiring undefeated in 1904.

Those who came after Jeffries got more inclusive with the belt.

Going Against the Galveston Giant

By 1908, 30-year-old Jack Johnson had a record of 46-5-8, including a number of titles defenses. But these defenses were all of the World Colored Heavyweight title. He’d never had a shot at the overall title and it seemed like he might never get one.

Then the belt fell into the hands of Tommy Burns. A Canadian, Burns declared, “I will defend my title against all comers, none barred. By this I mean white, black, Mexican, Indian, or any other nationality. I propose to be the champion of the world, not the white, or the Canadian, or the American. If I am not the best man in the heavyweight division, I don’t want the title.”

Let’s not overstate Tommy’s tolerance—newspapers also quote him making racist statements to justify avoiding black opponents. That said, Burns got in the ring with “Jewey” Smith. (That was the actual name used by a boxer, as this New York Times article demonstrates.) And when an Australian promoter shelled out the massive sum of $30,000, Burns agreed to take on Johnson for the championship. Johnson won the title by knockout—movie cameras documenting the bout were shut off rather than capture Johnson’s moment of victory.

Black and the Best

Johnson went on to hold the title for over six years. His dominance inspired Jeffries to emerge from retirement in attempt to, as Jack London suggested, “rescue the White Man.” That did not happen. Jeffries hadn’t fought in six years, but he didn’t let ring rust excuse his loss by knockout: “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

Johnson thoroughly enjoyed his success and his money, opening a jazz club and daring to having public relationships with white women. Perversely, even Johnson started drawing a color line. Not because of racism, of course—he simply reasoned he’d have more lucrative bouts against white opponents so he stuck to the money.

Johnson finally lost the title to the white Jess Willard in 1915. Willard in turn lost his title to Jack Dempsey in 1919. And Dempsey became one of boxing’s iconic fighters while highlighting the sport’s blind spot.

The Manassa Mauler Goes Missing

Dempsey developed a reputation for being brutal and fearless. 6’1” and under 200 pounds, he still savagely knocked out Willard (6’6” and at least 235) and “Wild Bull of the Pampas” Luis Firpo (over 6’2” and at least 220).

Dempsey even took on black fighters. This includes a 1916 bout against Lester Johnson in New York. Dempsey was newly arrived from Salt Lake City and Johnson was a local sensation. Johnson took the decision.

At least, Dempsey welcomed all comers before the title. Afterwards, he ignored worthy black contenders like Sam Langford. In fairness, once he had the belt Dempsey ignored pretty much everyone. Between winning the title on July 4, 1919 and losing it to Gene Tunney on September 23, 1926, he made just six defenses—less than one a year. (By comparison, he had won 18 fights in 1918 alone.)

Tunney beat Dempsey again in the 1927 rematch—it featured the notorious long count that Dempsey fans insist allowed Tunney time to recover after a knockdown. With that loss, Dempsey retired.

Now boxing was in the hands of a man with the potential to forever change the image of the heavyweight champ. The son of Irish immigrants like John L. Sullivan, Tunney was in every other way his opposite. A former Marine, he was noted for his constant reading. Indeed, his close friends included Nobel Prize for Literature recipient George Bernard Shaw, who wrote: “I have not been given to close personal friendships, as you know, and Gene Tunney is among the very few for whom I have established a warm affection.” Tunney even lectured on Shakespeare at Yale.

A true boxer rather than just a brawler, Tunney lost only once in his career, to the legendary (and legendarily dirty) Harry Greb. Tunney avenged the loss to the “Human Windmill” three times. With two decisions over Dempsey and still only 30, the sport seemed to be his. But Tunney fought only once more, retiring at 31. He promptly married an heiress, fathered a future U.S. Senator (whose successful run inspired the 1972 Robert Redford film The Candidate), found success of his own as a businessman, and lived a life of wealth to the age of 81.

Search for a Planet

The Hall of Fame boxing broadcaster and trainer Teddy Atlas told RCL that he uses the terms “planets” and “meteors” to describe top boxers. Meteors are fleeting—planets stick around. After Tunney, boxing was all meteors: Often intriguing fighters but ones who only managed to stay on top a short time.

This paved the way for a true planet in Joe Louis. The celebrated boxing scribe Bert Sugar wrote of the Brown Bomber: “But no heavyweight champion—and probably no sports figure—ever captured the imagination of the public, fan and non-fan alike, as the smooth, deadly puncher with the purposeful advance who, at his peak, represented the epitome of pugilistic efficiency. And no man was so admired and revered as this son of an Alabama sharecropper who carried his crown and himself with dignity, carrying the hopes of millions on his sturdy twin shoulders.”

It was a remarkable rise, so unstoppable ultimately even the color line couldn’t contain it. (It helped that Louis and his team pointedly avoided public scandal, where Jack Johnson had reveled in them.) The Bomber destroyed all competition until he ran into the German Max Schmeling in 1936, who unexpectedly knocked out the undefeated Louis. Louis responded by winning seven fights, at which point he got a shot at the fighter Damon Runyon dubbed “Cinderella Man,” James J. Braddock. Braddock had unexpectedly defeated Max Baer in a massive upset. (Baer also lost to Louis—today, Baer is best known as the father of Max Jr., Jethro Bodine on The Beverly Hillbillies, but should also be remembered for knocking out Schmeling and publicly embracing Judaism with a massive Star of David on his trunks.)

Perhaps sensing the good times weren’t going to last, Braddock’s manager agreed to have him fight Louis in 1937… on the condition he got 10 percent of Louis’ earnings for 10 years. Smart move. Louis knocked him out in the eighth round. Braddock fought only once more before retiring.

Louis, on the other hand, would still be successfully defending the title a decade later. None of them would be so momentous as his rematch with Schmeling.

The Human Race

On June 22, 1938, Nazi Germany was overrunning Europe and Joe Louis put the heavyweight title on the line against Schmeling, the man who had handed him his first and only loss. Barely two minutes later, Louis was triumphant. He was acknowledged, on this night at least, not just a great African-American fighter but a great American. The sportswriter Jimmy Cannon observed simply that Louis “is a credit to his race… the human race.”

Now Louis began his “Bum of the Month Campaign.” He held on to the title for 11 years, taking out challengers white and black. In 1950 he finally lost the belt to another black fighter, Ezzard Charles. Who lost it to another still black fighter, Jersey Joe Walcott.

And this is when another Great White Hope emerged to dominate the sport — albeit one a bit uncomfortable with that designation.

The Original Rocky

Rocky Marciano retired in 1955 as the undefeated heavyweight champ, with 43 knockouts in 49 bouts. He was simultaneously both less and more impressive than that record suggests. His resume probably should have at least one blemish on it, with a few calls that were close, if not outright questionable. He took a split decision against Roland La Starza in 1950. Ezzard Charles gave him all he could handle in 1954 before dropping a decision. Archie Moore always insisted Marciano got a long count after a second-round knockdown and the ref wasted additional time after he got to his feet, letting him clear his head and come back to win what proved to be Marciano’s final fight.

For another, Marciano was a uniquely flawed champ. He stood 5’10”, weighed only 190, and had a reach of just 68 inches. (By contrast, Tyson Fury reaches 85”—even Floyd Mayweather comes in at 72”.) He was never a graceful fighter—trainer Lou Duva noted that when he first watched him work out that “Rocky kept falling down.”

That said, another legendary trainer, Angelo Dundee, called him “the best-conditioned athlete out there.” Marciano was also a master of the power game—he could take your biggest shot but you damn well couldn’t take his.

Which is how Marciano came back to knock out Moore in that 1955 fight. And knock out both Charles and La Starza in their rematches.

His most famous bout came against Joe Louis, who took him on when he was 37. It sounds almost like a reverse Johnson-Jeffries, with a current champ facing a former titleholder who’s revered but past his prime. Except this was a rivalry notably devoid of bigotry (at least on a personal level), as Marciano grew up idolizing Louis.

Marciano knocked him out in eight and—according to Louis—stopped by later for a tearful apology: “Joe, I’m sorry.” (Louis also reported that when an athletic commission doctor told him he couldn’t fight for another three months, he replied, “Do you mind if I don’t fight no more at all?” It was indeed his last bout.)

Marciano retired at just 32 in 1955. He died in a plane crash at just 45 in 1969. In between, his life apparently turned surreal, if not unpleasant. In 1993, Sports Illustrated ran an article by William Nack titled “The Rock.” It alleges Marciano had essentially become a successful loan shark—SI describes him as “his own savings and loan.” He apparently kept no formal records and dealt in cash exclusively. (This was a well known quirk of Marciano’s—he once turned down a $5,000 check for $2,500 in bills.) In an unhappy marriage but unwilling to leave, Marciano also apparently indulged in an endless series of one-night stands, refusing to be with the same woman more than once.

Marciano’s attitudes towards race in the ring came at a time when non-white champs were later dismissed as unfit for civilized society, like when Jim Murray compared realizing Sonny Liston was the heavyweight titleholder to “finding a live bat on a string under your Christmas tree.” (Blunter writers just used slurs to describe Liston—tamer examples include “jungle beast.”)

Things Start Getting Complicated

With Marciano out of the picture, Floyd Patterson took the belt in 1956. When he died in 2006, The New York Times described him as “Good-Guy Heavyweight Champion.” He earned a gold medal as a middleweight at the 1952 Olympics. When he first won the heavyweight title, he was just 21, the youngest to do so. Like Louis before him, he was a black champion even white American could support. The New York Times’ Arthur Daley once described him as “the knight in shining armor battling the forces of evil.”

Patterson was so liked he could lose to a white man, then immediately fight him twice more and win both—becoming the first heavyweight to lose the title and take it back—emerging from the whole experience more popular than ever.

You probably aren’t aware of this trilogy. Why? Possibly because the world outside of Scandinavia never connected that deeply with Patterson’s opponent, Sweden’s Ingemar “Ingo” Johansson. (They didn’t have time to bond—he fought only 28 times as a pro.) For that matter, you may not have heard of Patterson. His career overlapped those of four of the greatest figures in heavyweight history or any other weight class, for that matter. Between them, Sonny Liston, Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, and George Foreman held the title from 1962 to 1978.

Patterson never got in the ring with Frazier or Foreman, but he fought Liston and Ali twice each—he went 0-4 with four knockouts. The two by Liston were quick, with Floyd failing to make it through the first round on either occasion. His first with Ali was legendarily brutal—Patterson insisted on calling him by his former name, “Cassius Clay,” and Ali punished him for that slight over the course 12 rounds.

Patterson is credited with saying: “I’ve been knocked down more than any heavyweight champion in history.” Even after retirement, the knockdowns continued. Ali managed to regain the title twice after losing it, topping Patterson’s trick. And Patterson lost his mark as youngest champ—ironically, the record was broken by another protege of his trainer Cus D’Amato: Mike Tyson.

With the result Patterson has been largely forgotten, even as this quartet stand the test of time.

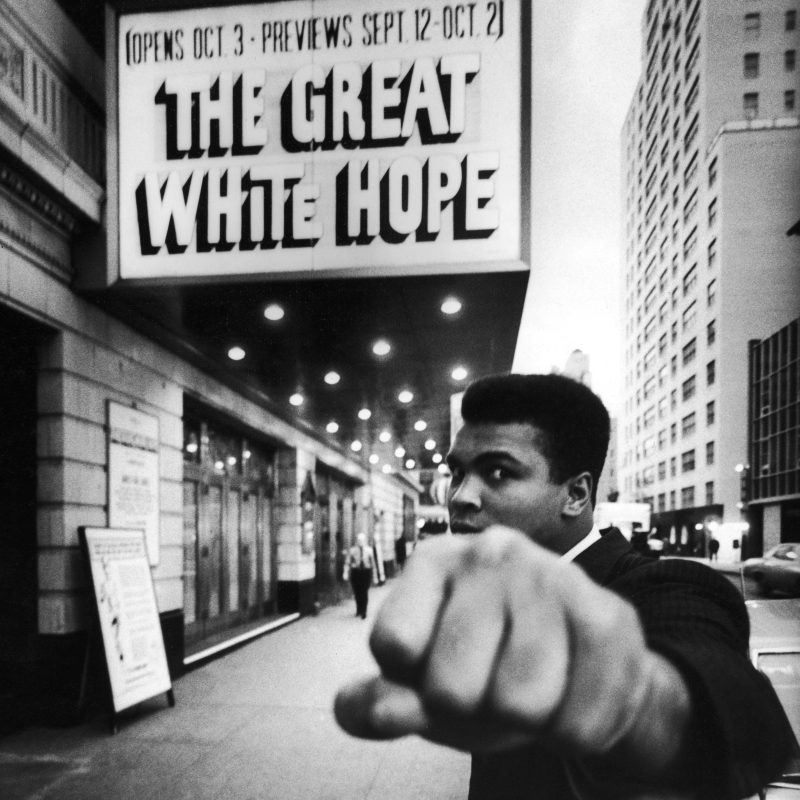

Beyond Race, But Not Bigotry

There has never been anyone like Muhammad Ali. Not in the heavyweight division, not in the rest of boxing, not in sports in general. This is a man banned from boxing for three years for his opposition to Vietnam, a man who met with Klan leaders (they shared his opposition to interracial marriage), and also a man who fought Superman in a comic book. Ali was a vicious trash-talking revolutionary—his descriptions of Frazier as a “gorilla” while promoting 1975’s Thrilla in Manilla remain horrifying to hear.

But the documentary Muhammad and Larry (about his 1980 fight with his former sparring partner Larry Holmes) reveals he was also a man who genuinely enjoyed performing magic tricks for children, who seemingly spent as much time at his training camp bantering with the crowds as he did actually training.

Plus he walked the walked like no one else. Decades after the bouts, we vividly recall:

-Ali knocking out the seemingly invincible Sonny Liston

-Ali getting up from a savage Frazier knockdown during their “Fight of the Century”

-Ali rope-a-doping George Foreman to score a shock Rumble in the Jungle knockout

-Ali barely outlasting Frazier to take the Thrilla in Manilla and the rubber match in their trilogy (a fight so brutal Ali noted it was, “Closest thing to dyin’ I know of”).

Why do we remember these fights? Because of Ali, of course, but also because he had such remarkable foils. Liston brought a menace to the ring previously unseen among titleholders. (It helped he had served two years in prison and had mob ties.) A sharecropper’s son, Smokin’ Joe relentlessly attacked, even as he was unfairly mocked as a sellout by Ali and others who felt his politics should be more radical. And Foreman seemed to be a combination of Liston and Frazier: He dropped out of school in ninth grade to run with street gangs, yet his waving of a small American flag after winning gold at the 1968 Olympics was viewed as a reproach to the Tommie Smith/John Carlos “Black Power” protest earlier at the games.

These three men were also devastating fighters: Against non-Ali opponents, they were a combined 161-8 with 134 knockouts. (Ali went 5-1 in his six bouts against them, with four knockouts and a decision loss to Frazier.)

Were there white fighters during this era? Of course. Ali fought a number of white opponents, like “Irish” Jerry Quarry, Karl Mildenberger, and George Chuvalo. Indeed, he fought Joe Bugner twice. But these bouts are hazy memories compared to the best efforts of this foursome.

And with Ali in particular achieving a stardom that went well beyond the sports page, it would have seemed that the myth of the Great White Hope could at last be put to rest. (Indeed, it had even inspired the title of a 1967 Pulitzer Prize-winning play and then 1970 film about Jack Johnson that mocked the very concept—the movie brought James Earl Jones a Best Actor Oscar nomination.)

Surely we could judge fighters by how they actually fought and at last leave race out of it.

Then 1982 rolled around.

Here Comes Cooney

Like Sullivan and Tunney before him, Gerry Cooney was Irish Catholic (though they weren’t raised in Long Island). By 1981 he was 24-0, including a first-round knockout of the former champ Ken Norton.

This landed Cooney a shot at Larry Holmes. Holmes was the heavyweight champ at the time. He had a record of 39-0 and had nearly beaten Ali into retirement. (The Greatest returned for one more equally disastrous bout.) With the benefit of hindsight, Cooney wasn’t ready. Even he mused in 2016: “I would have liked to have had a couple more fights before Holmes.”

With Don King marketing the fight, it became all about race. Never one for subtlety, King actually said, “This is a white and black fight.” Holmes was (correctly) dismissive of Cooney: “The great white dope. If he was black, nobody would know who he is.” Sure enough, Holmes won by TKO in the 13th. He eventually ran his record to 48-0 before a decision loss to Michael Spinks denied him a chance to match Marciano’s record.

Spinks, in turn, would get obliterated by Mike Tyson in just 91 seconds in 1988 in a fight that showed how far boxing had come since Jack Johnson.

Rooting for the Bad Guy

Teddy Atlas was Tyson’s first trainer. He said Tyson had remarkable gifts: “As far as punching ability, he’s like a Mickey Mantle in baseball. He could hit from either side of the plate just as well.”

Tyson captivated the world as he utterly obliterated opponents on his march to the heavyweight title. Then came a loss to Buster Douglas and a rape conviction and Tyson’s life and career generally fell to pieces. Atlas believes Tyson lacked the character that ultimately set fighters like Ali apart—Iron Mike was “fabulously talented, but just as fabulously flawed and weak when it came to the mental side.”

But here’s the thing: People still wanted to watch. Even without a title, Tyson somehow sold 1.5 million pay-per-views to see him take on Peter “Hurricane” McNeeley. (McNeeley is best known for threatening to bring Mike into his “Cocoon of Horror”—this apparently did not occur as McNeeley lost in the first round.)

Suddenly a belt, even the heavyweight one, no longer mattered so much. Possibly because there were so many of them.

More Is Less

For much of boxing history, boxers pursued a single title. There were downsides to this. Racist promoters, organized crime families, and other shady figures could deny a deserving contender a shot. But at least there was one positive: Having a belt meant something, because there was just one. By 1988, there were four boxing sanctioning organizations. That often meant multiple champs. Did this devalue the concept of being heavyweight champ? Well, when a champ literally throws one of his belts in the garbage—as Riddick Bowe did rather than accept a mandatory title defense against Lennox Lewis—it’s hard not to feel things have been cheapened.

Quite simply, heavyweight boxing no longer had its superstar, the Ali/Tyson, the man who commanded attention with or without the title.

But there was a young up and comer who seemed promising and, as luck would have it, he was white.

It’s Like a Movie (One That’s Deeply Depressing)

In 1977, Muhammad Ali starred in The Greatest. He was already 35, with a legendary career behind him.

Tommy “The Duke” Morrison was only 21 when Rocky V premiered in 1990.

Morrison’s nickname was due to a claimed family connection to Marion Morrison (better known as John Wayne). As a fighter, he showed genuine power. He began his career 28-0, with 24 knockouts, generally coming in the first round. It earned him a shot at the WBO title. Then he ran into Ray Mercer, a former gold medalist. Mercer got a brutal KO in five.

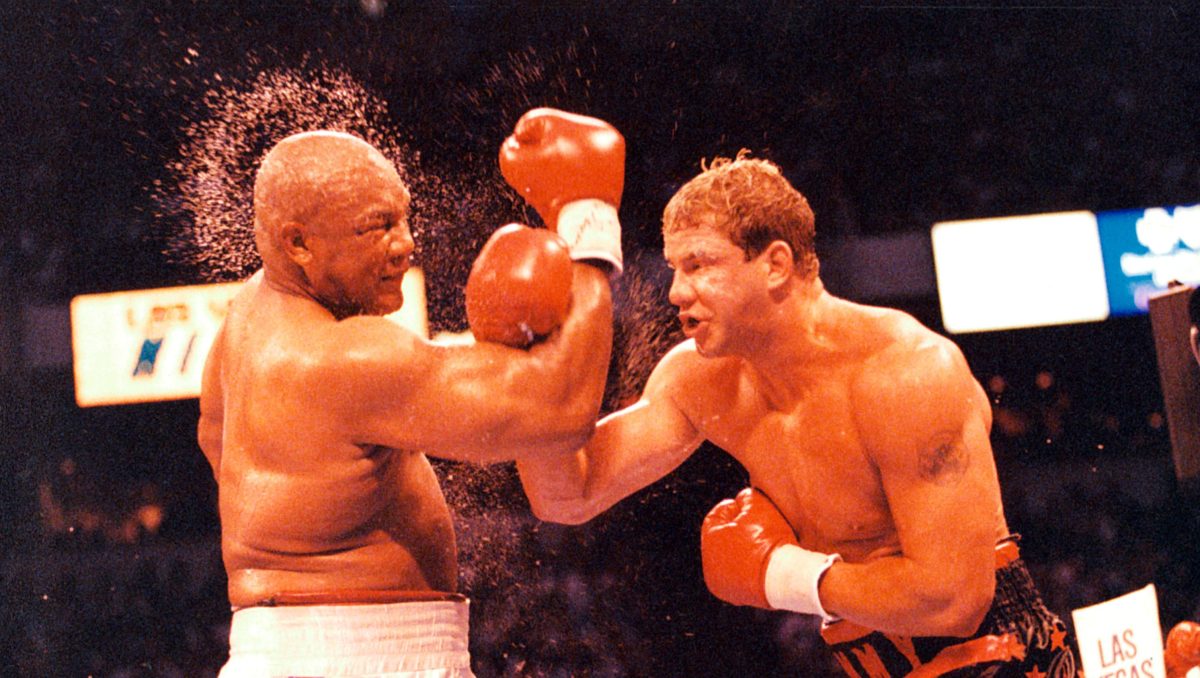

Morrison was notorious for partying, womanizing, and general poor decisions. (It’s believe all three of these contributed to his committing bigamy.) He pulled himself together for another title shot, facing George Foreman. Even at 44—a full 20 years older than Morrison—Foreman remained dangerous. Morrison pulled out a decision win, earning the WBO heavyweight title in 1993.

At last, boxing had its Great White Hope: white, American, a heavyweight champ.

It went poorly.

Mr. Self-Destruct

Morrison was oddly suited to the role of a Great White Hope. For one, his mother was a Native American. For another, the term implies somehow so strong he’ll somehow elevate an entire sport, a whole race. Morrison couldn’t even keep himself out of trouble. It took him just two fights to suffer a first round knockout to lightly regarded Michael Bentt. He pulled himself together and managed to win a share of the title again, stopping Donovan “Razor” Ruddock for the IBC heavyweight title in 1995. He held it only one fight, getting knocked out by Lennox Lewis.

It seemed Morrison could keep the strange pattern of his career going for years—impressive displays leading to a loss of interest followed by a humiliating loss followed by a return to form and repeat. Then the cycle ended. His promoter confirmed Morrison had HIV in 1996, which was discovered shortly before a scheduled bout against Arthur Weathers In Vegas. (Nevada was the only state requiring an HIV test at the time.) It seemed a career ender. After all, boxing is literally a blood sport.

With Morrison only 27, it appeared time for him to leverage his celebrity for a new chapter of his life. Except Morrison decided he didn’t have HIV, after all. It had (according to him) all been a false medical diagnosis. A decade after his retirement, he returned to the ring for two fights. Morrison granted Sam Mellinger of the Kansas City Star an interview in 2011. He talked about how he was healthier than ever, how HIV didn’t exist for anyone, how he once teleported himself out of a bar: “It’s real. But things like this don’t work for anybody that doesn’t believe it.”

Morrison died on September 1, 2013. He was just 44. January 2 would have been his 50th birthday. By the time of Morrison’s passing, boxing had at last had its prayers answered, albeit not in the way they may have wanted.

Getting What You Hope For

The irony is that the world eventually did receive a new Great White Hope. In fact, it got two of them. The Ukrainian Klitschko brothers were massive, with Vitali standing 6’7” and “little” brother Wladimir 6’6”. They were highly intelligent, holding doctorates in sports science and speaking multiple languages. And they were even the real deal in the ring: Both won titles and Vitali was 45-2 with 41 knockouts for his career, Wladimir 64-5 with 53.

They almost killed heavyweight boxing for the American audience, to the point that their fights weren’t offered as PPVs because clearly no one would buy them.

How did this happen? To start, they insisted they had promised their mother they would never fight each other, denying the public the one fight that seemed to offer actual intrigue. Vitali was unlucky—both his losses were due to injuries that caused fight stoppages and his career was cut short as well. Wladimir grew into a fighter both remarkable and sometimes remarkably hard to watch. After 45 bouts, he was 42-3, but all three losses were by knockout. He then reeled off 22 straight wins, with displays that might be best described as grimly efficient to ensure he avoided those fluke defeats. He was utterly dominating, crushing the competition. (Sometimes literally: Wladimir was a master of subtle tactics, like leaning on his smaller opponents so his weight would wear them down.) You couldn’t help but be impressed—he wound up 25-3 for his career in title bouts—but that didn’t mean you wanted to watch.

And suddenly something became clear: People would rather watch an entertaining black heavyweight champ than a dull white one.

Or an entertaining black heavyweight contender.

Or an entertaining boxer in general, regardless of race or title or weight class. Which is why the world came to embrace a Filipino who destroyed larger opponents like Oscar De La Hoya and Miguel Cotto.

And an unbeaten trash-talker from Grand Rapids, Michigan, even as he selected increasingly questionable opponents including non-boxer Conor McGregor.

Does race still play a role in fight promotion? Well, in 2017 McGregor instructed Mayweather to “Dance for me, boy!” There was even a tense moment before a recent heavyweight title fight. Deontay Wilder responded to Tyson Fury’s monologue about his fighting heritage as a gypsy by announcing, “You say your people have been fighting for 200 years? My people have been fighting for 400 years and are still fighting to this day.”

And how did Fury respond? The man with a history of homophobic and sexist remarks struck a surprisingly positive tone: “I don’t think we should bring this fight into a battle of races, or a battle of cultures or all that. This isn’t a battle of who’s been persecuted longest. This is a battle between Tyson Fury and Deontay Wilder. It’s not a battle of races or cultures.”

They then fought to a memorable draw, praising each other after. (Wilder: “We both go home as winners.” Fury: “He’s a great fighting man and I respect him.”) Their first bout sold roughly 325,000 PPVs. The rematch could do multiples of that figure.

Reminding us all that ultimately in boxing, as in so much of life, the color that matters most is green.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.