Donald Trump has praised China’s President Xi: “He’s now president for life, president for life. And he’s great.” Indeed, Trump occasionally describes Xi as “a friend.” Yet Trump’s also quick to criticize China itself: “There are people who wish I wouldn’t refer to China as our enemy. But that’s exactly what they are.” Generally, Trump clarifies that they’re an economic enemy. Even then the rhetoric often gets heated, as he notes China has been known to “rape our country.” This all has major global implications, as any new developments in U.S.-China trade talks can make markets around the world surge or shrivel.

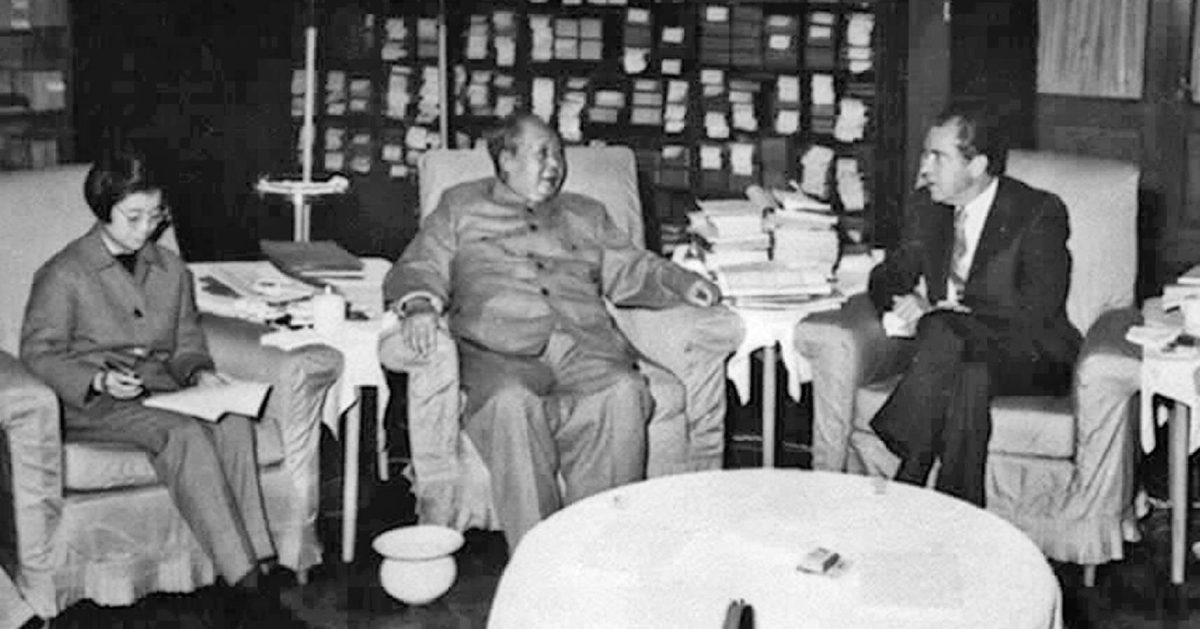

It’s also all oddly consistent with America’s overall relationship with China, one filled with unexpected tensions and rapprochements. On February 21, 1974, we experienced the most dramatic development of all when President Richard Nixon arrived in China for a historic meeting with Chairman Mao Zedong. (At least, in theory—Mao hadn’t yet committed to seeing Nixon when the latter arrived.) It was the first visit by an American president since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. This encounter continues to have major implications for both nations, not to mention pretty much everyone else on earth. Yet it only happened because of a combination of careful calculation and a wild leap of faith.

The Groggy Giant

Napoleon allegedly said, “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep, for when she wakes she will move the world.” Napoleon died in 1821, with China still soundly slumbering. The 20th century began with the failure of the Boxer Rebellion. This attempt to drive foreign nations (including Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Japan) out of China just led to humiliating concessions. The decades to come would bring more hardships including revolution, civil war, Japanese invasion, and a staggering amount of casualties from the “Great Leap Forward.” (The Great Leap’s horrific, punitive measures ultimately resulted in an estimated 45 million dead. In raw numbers, Mao is history’s greatest mass murderer, responsible for more deaths than Hitler or Stalin.)

But the potential was undeniable. China is the fourth-largest nation in the world in area (just behind the U.S.) and it already had the world’s largest population by the time Nixon was sworn in to the White House. Quite simply, it was a place that could not be ignored. Nixon acknowledged as much with a 1967 article in Foreign Affairs: “Taking the long view, we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors.”

Nixon was elected president in 1968, but he seemed an unlikely man to build the bridge. As a congressman, he was notorious for “red baiting“—in his eyes, virtually every opponent was soft on Communism. To reach out to Mao and the People’s Republic was to open himself to charges of hypocrisy, even to alienate his very base. But Nixon was always unusual, both as a politician and as a human being. It resulted in him successfully making a leap few others would have even attempted. (Indeed, a 2007 New Yorker article reports even those close to Nixon were initially baffled by his desire for a visit: “When [National Security Advisor Henry] Kissinger learned of it, in 1969, he thought that the President had lost his mind.”)

Nixon Knows No Limits

Nixon was a man who knew desperate times. While at Duke Law School, he lived for a time in a tool shed. He once became so worried about his grades and losing his scholarship that—in a preview of things to come—he broke into the dean’s office to check his transcript. (He was fourth in his class.) Similarly, while serving in the Navy during World War II, Nixon proved himself an exceptional poker player. He had a knack for bold bluffs, allegedly picking up the then massive sum of $1,500 on a pair of twos.

All these qualities would be utilized when connecting with China. Nixon recognized a moment when something remarkable was possible and worked hard to prepare for it. Yet even after all the groundwork, it was still a massive risk, one that could make or break him. As he had throughout his life, Nixon happily doubled down.

Potentially Huge Payoffs

In general, presidents like international triumphs. For Nixon, one was a borderline necessity. “At home, you had riots, assassinations and people being disillusioned with executive power,” recalled Winston Lord, a special assistant on Nixon’s National Security Council and later the American ambassador in Beijing. “He thought if he opened China, the huge country, the drama and the importance of dealing with the giant would put in perspective the rather messy exit from Vietnam.”

There was an added bonus to connecting with China: The closer it got to U.S., the more distant it would grow from the Soviet Union. While the Soviets and the Chinese shared a political ideology, tensions had long existed between the two sides. They had an explicit falling out in 1959, as Nikita Khrushchev felt that China had deliberately undermined his visit to the United States. In general, Chinese officials had noticed the way the Soviets took control of Eastern Europe and grew understandably wary.

“In Mao’s mind and the Chinese leadership’s mind they were really very concerned that this was a serious threat to them,” said Admiral Jonathan Howe, a military assistant on the National Security Council. “They didn’t feel we were territorial… but they thought the Russians would be. This was a motivating factor.”

Thus talks secretly began, with Pakistan serving as an intermediary. Then there was a public breakthrough via the ping-pong table. On April 6, 1971, while in Japan for the 31st World Table Tennis Championship, Chinese Premier Chou En-lai invited the U.S. National Table Tennis Team for a visit. The U.S. team accepted and arrived on April 10, 1971 for a series of exhibitions.

On July 15, 1971, Nixon announced he would be personally visiting China. He set the bar high: “If there is a postscript that I hope might be written with regard to this trip, it would be the words on the plaque which was left on the moon by our first astronauts when they landed there: ‘We came in peace for all mankind.’”

In 1972, a man who had once declared “it would be disastrous to the cause of freedom” if the U.S. recognized the People’s Republic of China headed to that very same country.

Meeting Mao

While his delay in personally welcoming Nixon generated a fair amount of suspense, Mao did eventually agree to see Nixon and the two came together in Mao’s private quarters. Already 80, Mao had beaten the odds simply by still being alive. One notable example: In 1934, Mao led the Communists on an epic retreat from Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. Dubbed the Long March, it covered 8,000 miles and saw an estimated 70 percent of its original 100,000 participants die.

Of course, Mao ultimately triumphed. He had been the unquestioned ruler of China for decades by the time he met Nixon. Which may be why the transcript of their encounter reveals a conversation where Nixon seems to be turning on the charm while Mao is coy, even teasing. “The Chairman’s writings moved a nation and have changed the world,” Nixon says of Mao. Mao’s reciprocal praise? “Your book, The Six Crises, is not a bad book.” (Mao also mused, “Those writings of mine aren’t anything. There is nothing instructive in what I wrote.”)

The meeting went well enough that the Shanghai Communiqué could be created. It offered a path to better relations between two nations with calls for increased trade and travel… and made a third country very nervous.

The Taiwan Tensions

When the Communists defeated the Nationalists in mainland China in 1949, Chiang Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists fled to the island of Taiwan. To this day, China insists Taiwan is part of the People’s Republic. The Shanghai Communiqué marked the moment when the U.S. publicly started to back away from Taiwan. Eventually, Jimmy Carter would revoke recognition of Taiwan and switch over to China.

Mathematically, this makes sense. China has roughly 1.4 billion people. Taiwan has less than 24 million. Most countries have made the same calculation the U.S. did. (El Salvador abandoned Taiwan in 2018, leaving just over a dozen nations on the entire planet that still recognize it.) Yet the fact remains a majority of Taiwanese see themselves as independent from China and wish to remain that way. By backing China over Taiwan, the U.S. has made a practical decision, but one that—as a younger Nixon warned —hardly champions freedom. (Incidentally, the people of Taiwan have historically had bad luck when mainland Chinese take over: Chiang Kai-shek imposed the brutal “White Terror” martial law that lasted from 1949 to 1987.)

Taiwan has proven too hot even for Trump. He accepted a phone call from Taiwan’s president in 2016, something no American president has done since 1979. It seemed that he was willing to risk a showdown with China. Within months, however, Trump reaffirmed the “one China” policy, ensuring that no matter how tense things currently get, the struggle won’t be taken directly to China’s backyard.

New Players, Same Play

Nixon won his wager on China, but soon after saw another gamble backfire badly when the Watergate break-in led to his resignation in 1974. Both Chou En-lai and Mao died in 1976. China and the U.S. need each other more than ever—we are the world’s two biggest consumer markets. Yet there remains a great deal of suspicion between the countries—an awareness that both are destined to be competitors and an uncertainty over the exact forms this clash will take. Chou En-lai once told the Americans, “There is chaos under heaven,” noting the world was awash with civil war and conflict. Forty-seven years later, a hint of chaos remains. Below, a translator from the Nixon-Mao summit recalls that historic encounter.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.