This week brought with it the announcement of a new national park, one which will eventually encompass 444 acres on the border of Nebraska and Kansas. The governing body setting this new park up isn’t the National Park Service, however; instead, it’s being established by the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska.

A report from the Associated Press notes that the Ioway Tribal National Park “will overlook a historic trading village where the Ioway people bartered for buffalo hides and pipestones with other tribes during the 13th to 15th centuries.” When it’s completed, Ioway Tribal National Park will join a growing number of tribal national parks across North America.

It’s worth mentioning here that this isn’t an exclusively American phenomenon. Similar parks have been established in other countries where Indigenous populations faced warfare, oppression and relocation in the name of colonialism. Booderee National Park, located on the east coast of Australia, is owned by the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community and jointly managed by Parks Australia and the Indigenous community there.

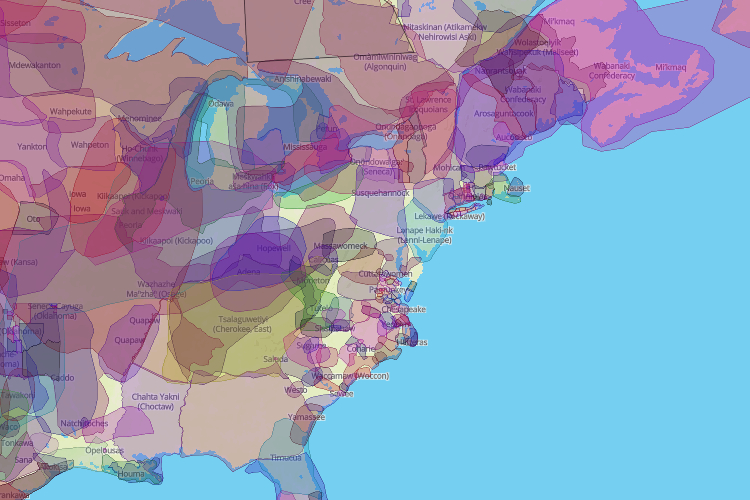

The Ioway Tribal National Park was made possible, in part, by a donation of land by the Nature Conservancy of Nebraska. That puts the park in line with two growing movements: One, of raising awareness of where Indigenous peoples have historically lived. The other involves donating land outright, which has taken place on governmental, institutional and personal levels.

That movement is not far removed from another factor in the establishment of tribal national parks: making sure that history is conveyed accurately and that visitors to sacred sites behave appropriately while there. The website for Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park mentions that several areas within Antelope Canyon can only be visited with a tour guide — something that helps keep the stunning landscapes protected for future generations.

Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park isn’t the only park handled by Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation. (One aside: all Navajo Nation parks are presently closed due to the pandemic.) Monument Valley, home to some of the most iconic vistas in North America, is also found within a Navajo Nation tribal park.

Located two and a half hours east of there in western Colorado, Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park also offers visitors a chance to see historical and scenic spaces, including the famed cliff dwellings there. Visitors also have the option to take a tour which involves climbing four ladders and hiking for four and a half miles. The park’s website stresses, though, that visitors must be accompanied by a Ute guide when they enter tribal lands.

Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park has been owned and operated by the tribe for over 40 years. Other tribal parks were established more recently. A 2016 article in the National Observer discussed the declaration of Dasiqox Tribal Park by the Tsilhqot’in Nation in British Columbia. The park’s website describes it as “a proposed land, water and wildlife management area located in traditional Tŝilhqot’in territory.”

The National Observer article quotes lawyer Jack Woodward, who worked closely with the Tŝilhqot’in, on what makes a tribal park distinct from other large-scale parks. “A tribal park recognizes the fact that you can still live on the land, and make a living from the land, and actually hunt and fish and trap and harvest those resources and it’s still there for the next generation,” Woodward said.

A 2019 High Country News article on the Blackfeet Nation’s efforts to establish a tribal national park offers a good overview of the issues at stake. It encompasses a host of reasons for why tribal parks are a growing concern, covering everything from Indigenous people having control over their own narratives to the economic incentives of eco-tourism. While it’s not the easiest of tasks, establishing a tribal park offers plenty of rewards — and the Ioway Tribal National Park is part of a movement that’s steadily growing.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.