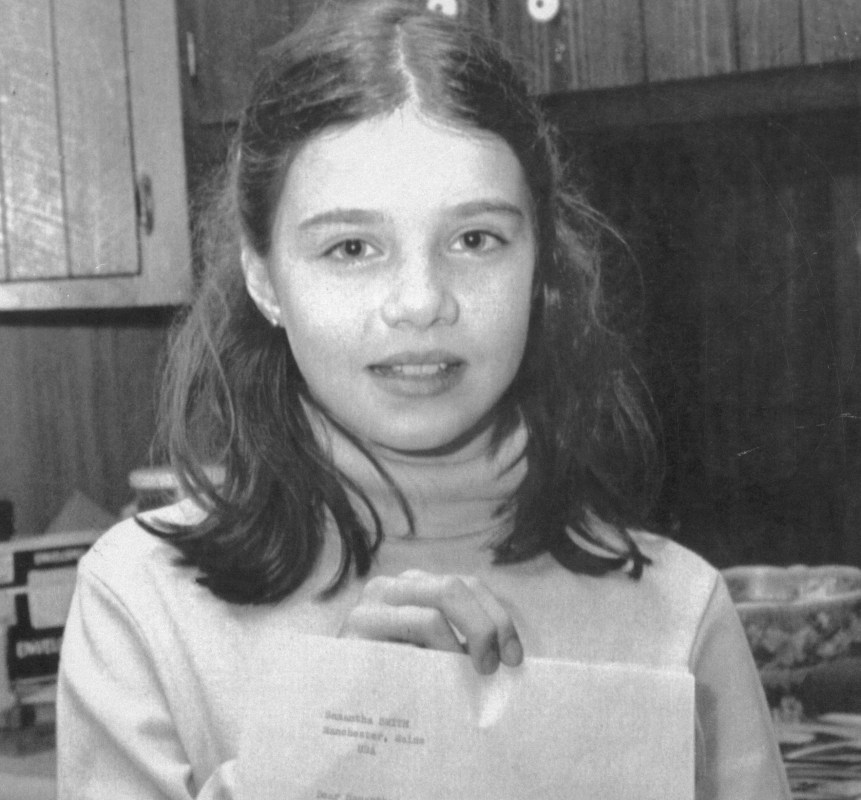

Thirty-five years ago today, an American schoolgirl in Maine received an unusual letter from an unusual pen-pal: then-leader of the Soviet Union Yuri Andropov.

“You write that you are anxious about whether there will be a nuclear war between our two countries,” Andropov writes near the beginning of the note. “And you ask are we doing anything so that war will not break out. Your question is the most important of those that every thinking man can pose. I will reply to you seriously and honestly.”

Andropov was referring to a letter that then-10-year-old Samantha Smith, had written him in December 1982, in which she first congratulated Andropov on his “new job” and then said with a child’s frankness, “I have been worrying about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war. Are you going to vote to have a war or not? If you aren’t please tell me how you are going to help not have a war.”

Smith’s letter was printed in the Soviet media, but it took another letter to another Soviet official to get Andropov to respond. In his note, Andropov said he did not want any nuclear weapons — Soviet or American — to ever be used.

“It seems to me that this is a sufficient answer to your second question: ‘Why do you want to wage war against the whole world or at least the United States?’ We want nothing of the kind. No one in our country — neither workers, peasants, writers nor doctors, neither grown-ups nor children, nor members of the government — want either a big or ‘little’ war,” the Soviet leader wrote. “We want peace — there is something that we are occupied with: growing wheat, building and inventing, writing books and flying into space. We want peace for ourselves and for all peoples of the planet. For our children and for you, Samantha.”

In closing, Andropov invited Smith and her parents to the Soviet Union so she could “see for [herself that] in the Soviet Union, everyone is for peace and friendship among peoples.”

When news of the letter reached the American media, Smith became an overnight celebrity.

On ABC’s Nightline that evening, Ted Koppel spoke to Smith and called the letter exchange “one of the most effective exercises in diplomacy that we’ve seen in this country in quite a while.”

Smith responded, “Well, I just hope we can have peace, and I hope it’ll do some good.”

But much more diplomacy and a show of Soviet soft power was to come after Smith decided to accept Andropov’s invitation. In July of that year, Smith and her parents went on a two-week trip to the Soviet Union, where they toured Moscow, what was then called Leningrad and the Artek summer camp in Crimea, with cameras flashing all the while. Photos from the trip show a smiling and laughing Smith with children her age.

While in Moscow, Smith and her mother, Jane Smith, had a press conference where they took questions from Russian children and adults. In response to one question, Jane Smith said the family planned to tell the Americans that “the Soviets are kind, warm people and that they too want peace and we need to talk more and become better acquainted with each other as people.”

Upon returning, the younger Smith was hailed as a peace activist and appeared on the Tonight Show With Johnny Carson, where she gushed about the Soviet subways (they had chandeliers), the “really good” handmade-stuffed animals and all the wonderful children that she met. She agreed when Carson said that kids are the same everywhere.

The entire exercise appeared to be a victory for the image of the Soviet Union, with Smith’s effusive praise of its modernity and suggested equivalence with 1980s America. In that, some people saw something more sinister. Andropov had been head of the KGB on his way up the communist ladder, after all.

Even in that first interview, there was a hint of skepticism about the idyllic trip behind the Iron Curtain, as Carson said he suspected there are “probably some things that maybe you’re not aware of, at your young age, that a lot of people are not too happy about in that country.”

“But I don’t suppose you saw too much of that side, did you?” he asked. Smith shook her head.

In another interview on NBC’s Today show, the interviewer’s final question was reportedly, “Do you know what the word ‘propaganda’ means?”

Some accused Smith’s parents of pushing their views on her. Others said the Soviet Union was just exploiting a naive child for good international press.

An undated declassified FBI document, obtained by RealClearLife through the Freedom of Information Act, alleged that one of the guides who had been assigned to Smith’s trip was “violent” and “anti-western.” The document said that tourists under this guide’s care are shown “a supposedly typical Moscow classroom, which in fact, is part of the [redacted] school for very high ranking officials.”

Regardless of the original motive, the Soviets understood Smith’s value to them afterward. Another undated, declassified FBI document says that a photograph of Andropov and Smith, who actually never met in person, would be surreptitiously placed at the United Nations in Geneva when then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan was to meet with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev there. “…President Reagan will have no idea it is there prior to the meeting,” the FBI document says, adding that maybe someone should warn the White House.

Smith was robbed of the chance to evaluate her adventure and the criticism that followed from an adult’s perspective. She was killed along with her father in a plane crash in 1985 at the age of 13, after traveling the world to promote peace and cultural exchanges. She once floated the idea that the leaders of countries should let their granddaughters (or grandsons, if they must) go to a rival nation so everyone could have a “better understanding” of the world.

At the time of her death, Reagan wrote to her family to say, “Perhaps you can take some measure of comfort in the knowledge that millions of Americans, indeed millions of people, share the burdens of your grief. They also will cherish and remember Samantha, her smile, her idealism and unaffected sweetness of spirit.”

The Russians reportedly named a rare diamond after her.

Smith’s journey didn’t end the Cold War, which dragged on for another six years, but at least for a time, it seemed to thaw a bit. More than three decades later, with relations between the U.S. and Russia at perhaps their lowest point ever, maybe it’s time to send in the kids.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.