My favorite race to rewatch on YouTube is the iconic 4 x 800-Meter at the 2010 Penn Relays.

It’s the one where Robby Andrews, a future Adidas runner, but then just a 19-year-old freshman for the University of Virginia, slingshots past two competitors on the final bend for an improbable victory. As deep as the 600-meter mark, it appeared Andrews had absolutely shot at winning that race. Not least because the guy he passed in the final seconds was Andrew Wheating, a senior and a five-time NCAA champion who’d represented America at the Beijing Olympics two years prior.

But UVA’s gamble (putting someone so green on the closing leg) and Andrews’s gamble (purposely letting one of the best runners in the world toast him halfway through the race) both paid off. He left himself just enough time to win. The finish gave us two enduring images: the freshman’s shocked face as he saw his team’s time — an absurd 7:15.38 — and his gold necklace, flopping about his torso in celebration.

The running chain is an unlikely accessory. It doesn’t seem at home in sticky temps, when most serious runners prefer to go shirtless, or in the dead of winter, which is the last time you’d want a hunk of cold metal hugging your neck. It doesn’t appear to offer much in the way of aerodynamics, either — for a sport whose athletes prize paper-thin apparel, entertain race-day hacks (from nasal strips to beet juice) and will willingly wear the shoes of a competing brand in the name of a PR, where’s the logic in putting a necklace around your neck?

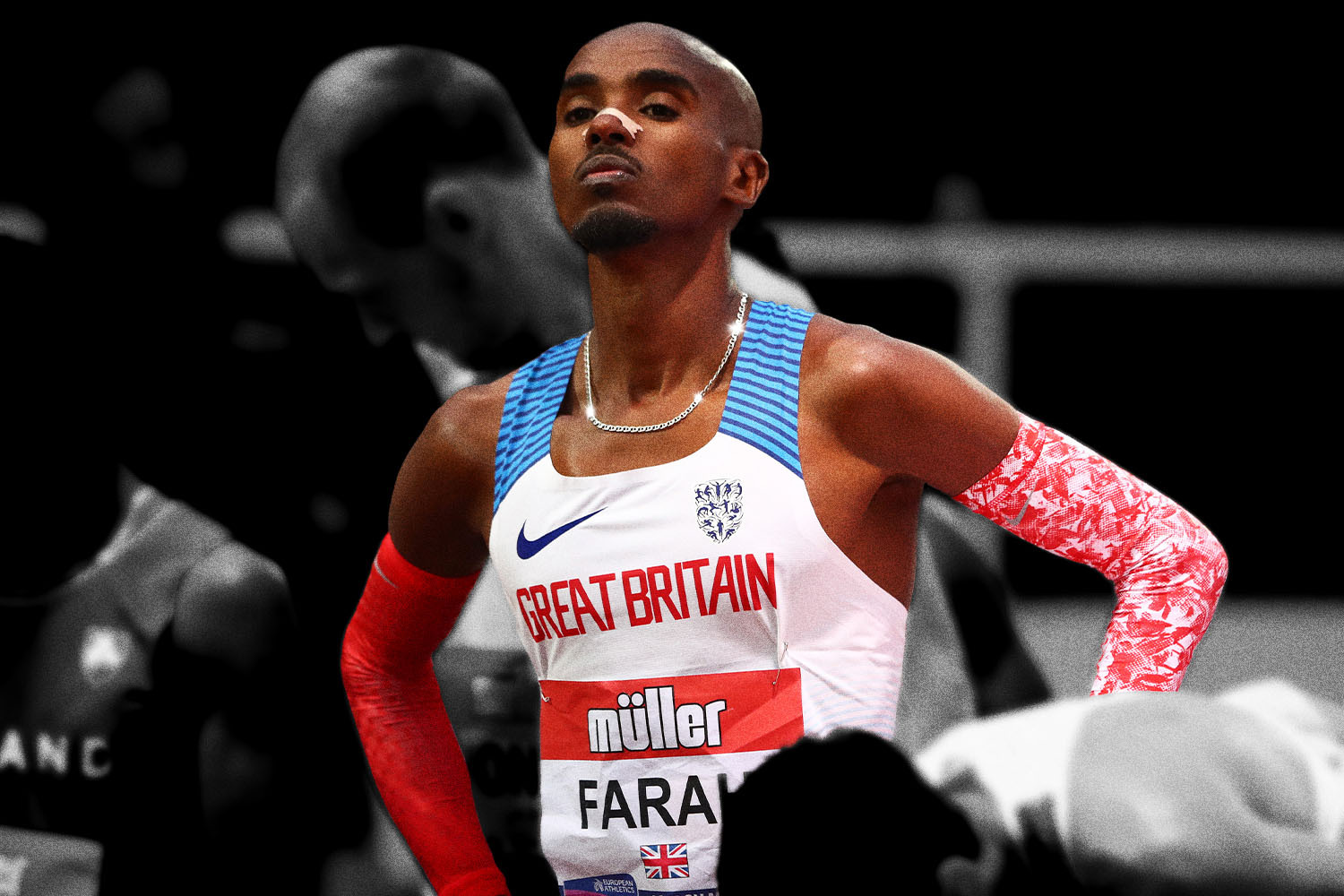

Consider: Andrews, his epic kick notwithstanding, is far from the most famous runner to compete in a race with a chain. Mo Farah wore one throughout his career. Bernard Lagat, too. Galen Rupp still wears one. And young stars like Cole Hocker, Paul Chelimo and Cooper Teare, currently tearing up distances from the 1,500-meter to the 10K, apparently don’t even show up to track workouts without their chains.

Their ubiquity at the very top of the sport has prompted some to wonder “how fast” one must be to convincingly show up to a meet or road race with one around their neck. As one runner queried the LetsRun community: “Could a middle of the pack D3 runner wear one without embarrassing himself?” This sort of question seems to accept the premise that the pros are ideally suited to (and deserving of) accoutrement. They’re operating at such a high level that a little silver or gold can’t hurt them; it’ll only add artistic flourish.

While there are pros who might sport bling for the look alone — not a bad idea, considering the endorsement pie is small for runners, as is their window to creatively capitalize on it — never forget the gravitational pull of superstition. High-performing athletes have a tendency to create what the anthropologist Dr. George Gmelch once called “instruments of magic.” Gmelch was specifically referring to the ritualistic wackjobs who inhibit professional baseball dugouts (where borrowed bats, smelly socks and unkempt facial hair take on spiritual meaning), but no sport is truly immune.

Like baseball, running involves endless repetition of a task, leading to an eventual public demonstration. If you usually wear a chain during training, or — better yet — wore one the last time you set your personal best, it’s now necessary to your success. It’s folded into a routine that would already seem maniacal to passersby unfamiliar with the messy interior of the sport: going to the bathroom six times before a race, listening to the same song on repeat for an hour, taking jittery straightaways from the line until the race operator shows up.

That’s the irony of the running chain. It looks cool. It gives long-distance some of the panache it’s long been too shy to admit that it craves. But it’s also, in some cases, the descendant of whatever cocktail of nerves and uncertainty leads runners to it in the first place.

Other runners, meanwhile, start wearing necklaces because they’re sick of following a silly rule. In high school athletics, runners face penalty if they rumble into the finish line with any jewelry on — necklaces, earrings, even Livestrong-style bands. Prep stars have actually been disqualified from races. These rules, which were reinforced as recently as two years ago by the New York State Public High School Athletic Association, are reportedly to “protect” runners from coming into contact with the jewelry of one of their competitors.

But the NCAA has no such rules. Runners can even wear rings, if they so choose. As one girls cross country coach told Syracuse.com: “In college, everyone wears jewelry. You don’t see anyone losing an eye.”

College running is where the next crop of long-distance phenoms first get to experiment with accessories. It gives them room to start emulating their running heroes, or in some cases, study them from the same starting line. (Extremely talented collegiate runners get chances to rub shoulders with the pros.) Similar to mainstream sports stars, who enter leagues wearing certain wristbands, or requesting certain numbers, as an homage to a hero, it makes sense that running chains have become a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, “reserved” for the front of the pack.

But there is no reason that you — a middle-of-the-pack Division 3 runner, a casual jogger or a dad about to tackle his first marathon this weekend — can’t run with a chain. I’ve worn one for a little while now, and can attest that it checks a number of boxes, and one that I wasn’t expecting. For instance: I like the extra swagger it gives me, I like the ritualistic nature of putting it on before a fast four-miler and I like the way it bounces against my chest.

If there is any performance boost to be gleaned from a running chain, it’s that — cataloguing the clang of the metal against your torso forces you to reckon with your cadence. Is is picking up? Is it slowing down? Is it going side to side now? Perhaps my form is falling apart? It’s helpful to go into a little world when running (with the help of music, usually), and ignore all other stimuli. But sometimes, that stimuli is there to help you become a better runner. The running chain can offer a bit of nudge in that direction.

If you want one for yourself, there is an overwhelming variety of options online. Etsy has an entire shop of “running necklaces,” complete with pendants that read 26.2 or display winged feet. You can go that route, or if, you’re religious, go that route, but I’m a fan of keeping it simple. Ideally, you want a curb or cable necklace at no longer than 20″, though 18″ is best. The key is to keep it short enough that it isn’t hitting the center of your sternum, which is unpleasant. Longer than that, and it’ll retreat towards your back, hiking up towards your Adam’s apple, which also stinks. My necklace is 18″ and sits just below the collarbone.

If you’re looking to test trial this entire operation, and still aren’t sure you should be impersonating Mo Farah before you can finish a 5K, just start with something small. This option is $19 at Amazon. If you’re ready to commit to something more, find inspiration through our jewelry-buying guide, here.

And if you’d rather accessorize in different places entirely, take note of a different trend that’s sweeping the running community, brought to my attention by our in-resident marathoner, Becky Wade Firth. She’s noticed Kenyan-made ArtiKen bracelets popping up on the wrists of pro runners throughout the sport. They’re 100% waterpoof, contribute to clean water initiatives with each purchase and mad cool. Here’s our favorite.

Whatever you opt for, I recommend visiting a local track not long after and doing your best Robby Andrews sprint to the finish. It’ll feel as good as you look.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.