Earlier this week, before a 15-minute Tabata session on the Peloton with Leanne Haisnby (translation: a brutal HIIT cycling workout), I cracked a smelling salt capsule and held it about half a foot from my nose. My airways immediately went full Looney Tunes; the mucous membranes of my nose burned and it felt like steam was puffing out my ears. I chanced a glance in the mirror — my eyes looked like they’d taken a liter of shampoo — before clipping my shoes into the bike and starting my class.

Smelling salts occupy an exceptionally odd cross-section of the internet. For the younger generation, they seem like a fun, mysterious new invention — an opportunity to “do” a “drug” and film the hilarious results, seemingly without any real consequences. YouTube has six-minute long compilations of high schoolers and college students ripping smelling salts in cars and libraries; invariably, the inhaler screams or makes a funny noise while the person holding the camera laughs their ass off. Viral content machines like Barstool Sports have cashed in on this trend, too, tasking a younger employee to “culture” the entire office on what it feels like to take a smelling salt.

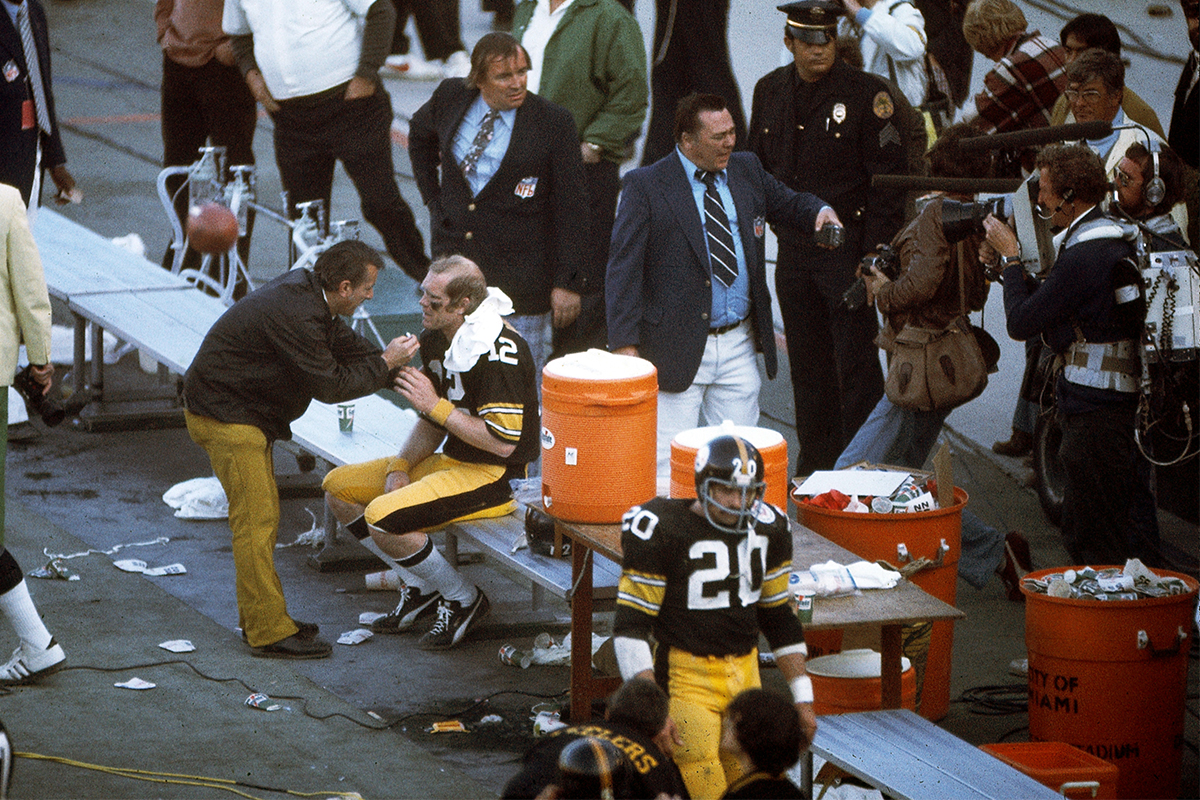

But that culture goes back way further than just the last few years. Smelling salts are a relic from antiquity. They were referenced in the writings of Pliny two millennia ago, and Chaucer 600 years ago. They were commonly carried around by doctors in the Victorian era, while during World War II, every standard-issue first-aid kit contained sal volatile, which is an ammonium carbonate solution, often mixed with alcohol. Throughout the centuries, the use case of smelling salts has been pretty clear: it’s intended to revive someone who has fainted, been knocked unconscious or is generally dazed. Most recently, they’ve been used for that purpose in the National Football League.

In 2005, New York Giants legend Michael Strahan estimated that 80% of pro football players were regularly using smelling salts during games. At the time — the height of the PED era in football, baseball, cycling and boxing — sports media clutched its pearls over the strange cartridges scattered along the sidelines. Following a four-month investigation, The Florida-Times Union ran a story with the headline: “A whiff of TROUBLE?” In the piece, Strahan and others described a ubiquitous ritual whereby players “used [smelling salts] as a performance enhancer, providing a powerful punch to propel them through rough practices and brutal games. Once the rush wears off, players open a new cartridge and take another whiff.”

That approach represented an evolution from original objective of smelling salts. Instead of solely making a player alert enough to shake off “getting his bell rung,” smelling salts could be used to go ring someone else’s bell. Or, in the case of Peyton Manning and Brett Favre, to accurately launch the ball downfield. Which, by the way, is how the NHL uses smelling salts, too — to increase alertness and get the most out of a given stretch of time on the ice. Many hockey players can’t imagine starting a shift without taking a hit. Sports Illustrated called the habit “an aromatic alarm clock.” One devoted player testified: “It wakes you up. It’s almost like a cerebral way of saying, ‘Hey, it’s game time now. It’s time to get going.’”

But is any of this a good idea? A 2006 essay published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine defined smelling salts as “preparations of ammonium carbonate and perfume, sniffed as a restorative or stimulant.” The ammonia gas, clearly, is the active ingredient. When it irritates the nose (infiltrating the lungs soon after), the body experiences an inhalation reflex. You legitimately couldn’t stop it if you tried. It sends a rush of oxygen directly to your brain, which immediately induces rapid, focused respiration. There is absolutely no doubt that it “works.” The better question is: Do we want it to? Should this practice continue? And might it have any place in other sports, especially the endurance favorites — running, cycling, swimming — of middle-aged laymen?

It’s telling that boxing banned smelling salts over five decades ago, while somewhat confusing that similar high-contact sports like football or hockey are yet to do the same. (It’s true — since Strahan opened up about the practice 16 years ago, none of the four major professional sports leagues nor the NCAA have bothered to regulate smelling salts.) Boxing banned the practice out of fear that smelling salts would obscure a more serious injury. The logic is pretty simple: if you’re woozy enough that you need smelling salts to be revived, you probably shouldn’t be revived for the express purpose of continuing to get punched in the head.

The NFL has a few dozen more pressing matters on its plate right now, but it’s courting a bit of risk by allowing teams to use smelling salts. The league already has a checkered concussion protocol; given that context, the optics of turning a blind eye to a “shake it off” stimulant aren’t great. Not to mention, that knee-jerk inhalation reflex can be somewhat violent for certain players. What if they’re on the ground with an injury to the cervical spine? As for perfectly healthy players who use it as stimulant, they might (for a couple minutes, at least) consider themselves invincible, and ignore injuries or over-exert their bodies. Smelling salts don’t confer superhuman strength, but studies have shown that athletes derive psychological confidence from that initial burst of alertness.

The primary piece of advice for aerobic athletes interested in smelling salts? Just don’t overdo it. Don’t hold the tab too close to your nose (anything closer than four inches could actually burn your nasal passages); don’t do them if you have a respiratory issue like asthma; definitely don’t take multiple hits in a short period of time.

To be fair, I understand the appeal of something like this. I’m an endurance athlete. The margin of error in a sport like running is razor thin. That’s why performance tech is having the moment it is. That’s why runners are obsessed with massage guns, beet juice and foam toe separators. The idea of adding an easy game-changer to a pre-race routine — especially something legal — is almost intoxicating in itself.

Here’s what I can say: I went with Smalts. The brand seemed reliable enough, and was an improvement on one of Amazon’s top options, a product called Bottled Insanity, which one reviewer compared to “a ride through the depths of hell.” Smalts is still a tad questionable (the brand bio reads “Three college students who fell in love with smelling salts” … oh boy), but my 15 tabs arrived in a handsome tin a couple days after ordering them. I did feel that promised alertness during my workout, and had a good session, cracking the top 1,000 riders (out of over 65,000), but I didn’t break any personal output records. That’s in part because the sensation wears off after a few minutes, and Peloton doesn’t have any intense classes less than 10 minutes long.

It’s why smelling salts are probably way more useful, from an athletic perspective, for powerlifters looking to deadlift or bench press a massive amount of weight, and sprinters or middle-distance runners searching for an extra bit of adrenaline coming off the blocks. It’s difficult to imagine a single coach (let alone medical professional) who would recommend that anyone smelling-salt their way through a full marathon or triathlon. Inhaling a cartridge could maybe be beneficial for waking oneself up at the start line (pre-race sleeps can be notorious) or as a pick-me-up at the halfway mark, but the worries of dependency and misplaced trust start to emerge; after all, there are more “natural” methods to prepare oneself for a race, like rest, hydration, meditation, high-carb energy gels, sugary bars or waffles, and even coffee.

There are some cautionary tales on online message boards linking smelling salts to pulmonary edema (a very scary condition where fluid collects in the lungs). At the moment, no scientific studies have confirmed negative longterm side effects from the recreational use of smelling salts. That said, no research has exactly proven their innocence, either. It leaves us, for now, with common sense, which suggests that snorting a chemical reaction to play, run, bike or swim with a bit more inspiration for a few minutes likely isn’t the best idea. Going forward, smelling salts should continue to do the job they’ve done admirably for thousands of years — resuscitate people in dire need of resuscitation.

If you’re an anaerobic-focused athlete with no history of asthma who’s tested smelling salts before, then sure, go ahead and crack open a capsule in a crucial performance situation. But don’t get it twisted: you’re the one lifting that barbell, pumping your knees or attacking an opponent. Don’t let the ammonia steal your glory. Oh, and for the love of god, try not to snort these things on TikTok. We don’t need a peer-reviewed study to know they don’t mix well with a plate of Tide Pods.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.