Last week, I stood at the top of a hill on a Tony Soprano cul-de-sac in Northern New Jersey, ready to race 6.2 miles against a man I’ve never met.

It was well past dinner, and the sun had already dipped behind the small mountains along the New York State border. I felt light. I’d eaten two bananas and chugged a cup of beet juice an hour before, and was wearing a a striped singlet and a pair of my lightest racing sneakers, Saucony Endorphin Pros. When I crouched into a starting position, my finger hovering over Strava’s “record” button, I hesitated for a second, muscle memory urging me to wait for a gun, or at least a whistle, before remembering that I was all on my own.

Since the start of June, Brooklyn-based running collective Trials of Miles has been hosting a single-elimination tournament called Survival of the Fastest. Conceived by erstwhile Amherst College runner Cooper Knowlton, the March Madness-style contest comprises two 64-person brackets — one men’s, one women’s — and six rounds of varying distances, which are, in order: 5K, 10K, 1 Mile, 10 Miles, 5 Miles and a 2-Mile championship. The rules are pretty straightforward: runners have almost an entire week (Monday to 3:00 P.M. the following Sunday) to send in a time via the tracking app of their choice. They can run the race as many times as they like, until they’ve settled on an official time, and can run it pretty much wherever they like. The only outlawed surface is a treadmill.

It’s hard to remember, now, that a couple of prominent road races actually took place in 2020. Atlanta hosted the U.S. Olympic Team Trials Marathon in February, for instance, and Tokyo managed a scaled-back version of its marathon in March (the only major to actually occur this year — Chicago, London and New York still have hopes for the fall). But across the country and globe, countless half-marathons, 10Ks, 5Ks and road miles fell victim to COVID-19’s early spring arrival, ending seasons before they began. There was an abruptness to that new normal; I’d trained through the winter with a Manhattan running club preparing for the New York Half (though I wasn’t scheduled to run it). Ten days before their race, it was still very much on, and I remember a chorus of “Good lucks” and “Hay’s in the barn!” from coaches as we legged out one more track workout of 400-meter repeats. The event was canceled the following week.

Fortunately, those miles didn’t go to waste. Just as beginners and lapsed joggers turned to running after gyms closed, vets wasted no time in patching together virtual runs and races. These events have been predictably all over the place, and are still going strong. As early as the first week of April, ultra-marathoners were running laps around their blocks in a diabolical contest named the Quarantine Backyard Ultra, which called for 4.1667 miles to be run every 60 minutes (for as many consecutive hours as competitors were able). In May, brands like Tracksmith, WHOOP and Hyperice teamed up to host The Perfect Mile, a running event in support of the United Nations’ COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. And later this month, Amazon’s even hosting a Wonder Woman-themed 5K and 10K series.

The fact there isn’t a purse for many of these contests, nor a medal, nor any of the usual swag hawked in branded tents outside a community race, doesn’t seem to matter to most runners. The entry for Survival of the Fastest was $12; the payout is $400. It speaks to the health of the sport at large and the motivations of the amateur runners who are increasingly driving its direction, as well as the lessons event operators might learn heading into a post-pandemic running world.

I only knew to sign up for Survival of the Fastest thanks to a Slack from a fellow runner at this company, who figured I’d be interested. I was registered five minutes later. There are more than just 128 runners in America, of course; and there is a high schooler, somewhere, who could probably handily win every round of this competition. But that “Fastest” moniker still means something, because it reflects a contract made (as in any race — virtual or in real life) to determine a precise winner from a specific sample size of competitors. It’s a small-town mindset, almost, and it mixes with another idea, however irrational: Hey, I could win this thing. When runners don’t win, or officially process that they in fact cannot, they fall back on impressing others. Or impressing themselves. All told, it keeps runners showing up — even when it’s virtual, even when there’s no goodie bag at the end.

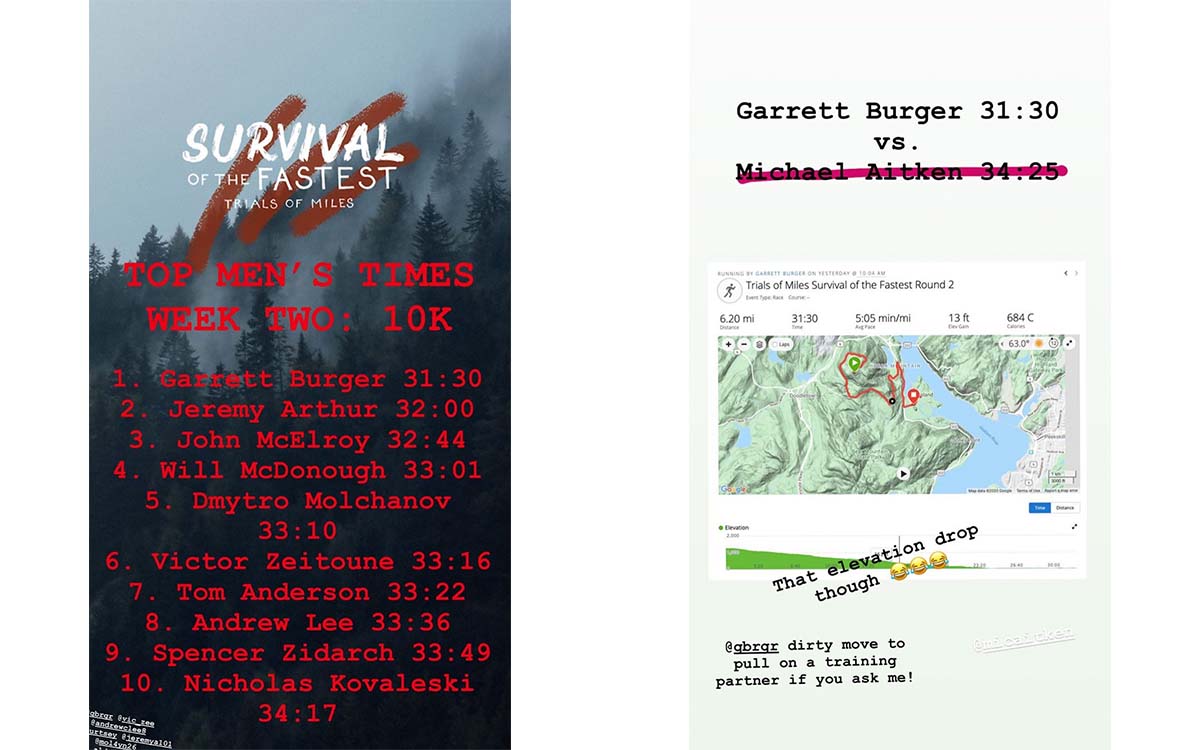

A bit of showmanship on the part of event operators, of course, can only help. Full disclosure: I’ve been eliminated from Survival of the Fastest. I ran a 16:41 5K in the first round to advance (my opponent ran a 17:58), and then a 35:12 10K in the second round to lose (my opponent toasted me with a 33:01). I’ve have had some time now to relax and enjoy spectating the tournament, which has updates on Trials of Miles’s Instagram page each day, and I recently caught up with Knowlton after the Round of 32 ended. On creating this event, he said: “I think running is inherently a really exciting sport, but too often it’s packaged really poorly. The main thing that interests me is trying to come up with races and challenges that are exciting, somewhat unconventional, and also viewer-friendly.”

Survival of the Fastest has been all the above, with a variety of quirks that have led to some bonkers developments, even just three weeks in. The tournament is completely unseeded, for example, and by sheer, blissful happenstance, the two fastest runners in the entire competition had to face off immediately. One ran a 15:47, the other a 15:42. Mr. 15:47 is now pacing his far slower friends, who all advanced. The prevalence of downhill runs, meanwhile (a logistical allowance, so Knowlton doesn’t have to source through elevation change data to make sure people aren’t cheating) has resulted in people literally driving to mountains and throwing themselves down steep trails. A friend of mine who’s been following the tournament messaged me the other day: “So the guy who ran a 31:30 decided to just jump from a plane.”

A tournament like this also directly engages with the extensive online presence of runners today, on both social media and Strava. Publicly posting your time early in the week, or sending it in to Knowlton (who will then publicly post it) takes some supreme confidence. It’s probably a smarter move, from a gameplay perspective, to run it privately, stalk an opponent’s page, and only send in your time once you’re sure of the head-to-head result. When I ran my 10K, for instance, I quietly recorded my first attempt on a Monday, logging a 35:37. My opponent ran more than two minutes faster than me two days later (I woke up to this stomach-curdling news thanks to a Strava notification) and I spent the rest of my week imagining beating him, like Rocky putting that newspaper cutout of Ivan Drago on his bathroom mirror. I had a radically different weekend because of this, too — no drinks on Friday, the assembly of a specialized, uptempo playlist, waiting all day for the humidity to dissipate, a 25-minute drive to start somewhere with more intense hills on Saturday — even though I knew the whole time I couldn’t win. A two-and-a-half-minute PR over four days would’ve been cause for a book deal.

But I had to try. Other runners in the competition, and runners in general, understand this. We’re a breed united by our love of chasing quixotic dreams; that’s what all those sidewalk chin-nods aim to encapsulate. Events that best appreciate that simple truth — that indulge runners’ urge to collect names and numbers like middle schoolers flipping through trading cards, to catalogue who’s fast, to speculate on who might be able to beat whom — are doomed to succeed. Knowlton, for one, has more ideas up his sleeve, especially as the lockdown eases up. He’s already created a FKT challenge (“Fastest Known Time”) called the The Four Bridges, where runners work to cross the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges, starting and ending at the same place, as quickly as possible. The current lead time, for a distance of something-like-14-miles, is just over 70 minutes.

The top three on that leaderboard might have all run the challenge differently. But that’s the point. Ideally, the creativity compelled by quarantine will translate to more and more challenges in the world of amateur racing, especially once social distancing ends. On the days ahead, Knowlton said: “I want to continue playing with the running tournament concept, but I think after this tournament is over I’m going to take a break from virtual racing. I think there’s some virtual-racing fatigue going on right now.” Instead, he’s planning his hustle’s eponymous event, The Trial of Miles, which will take place in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park in July. Runners will have to run timed miles and make the cut — 9:00, 8:00, 7:00, 6:00, 5:30, 5:00, 4:30 — over and over again, until no one else is left.

Until then, though, the Survival of the Fastest bracket continues. I’ll miss being a part of it. Going for a run, as thousands have realized over the last few months, is an unusually fitting disruption to the daily grind. Racing takes it one step further, giving it stakes. And throwing it all into an unseeded March Madness-style tournament is a special brand of insanity. For a couple weeks, without even seeing another runner, I had those bus-to-the-meet butterflies again. If you’re looking to follow along on this wild journey — why not, baseball’s never coming back and basketball could be doomed, too — head here for updates. This week’s the mile.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.