You’re at home watching TV, at work in front of your computer, or out to eat with family. Suddenly, there’s pressure in your chest, throbbing in your left arm and jaw. Your breathing quickens; you begin to sweat.

You’re thinking: Heart attack.

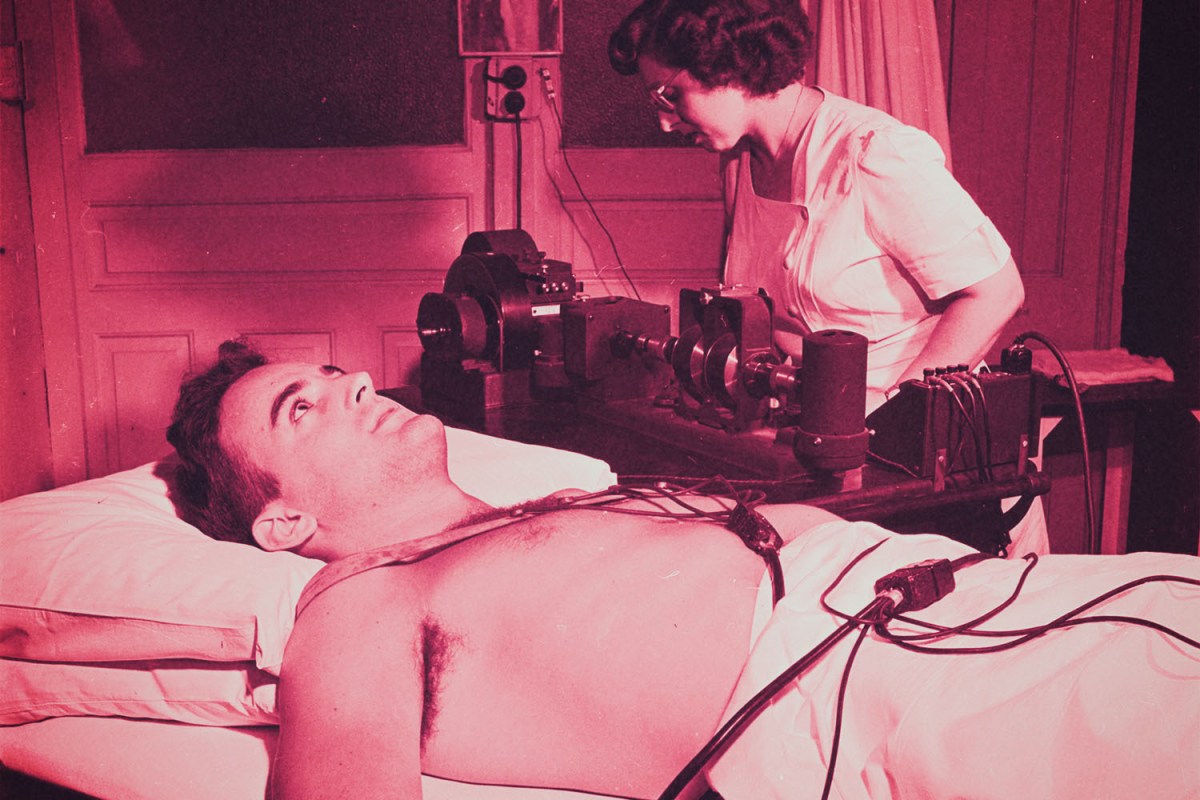

You rush to the hospital, but when the doctors and nurses are through with their myriad tests, they say there’s nothing physically wrong with you.

They’re thinking: Panic attack.

For many of the patients who live through such a scenario, this is the beginning of their journey toward improved mental health. The panic attacks may not cease immediately, but over time, talk therapy and perhaps some prescribed medication can help ameliorate their anxiety. Next time, instead of heading to the hospital because they’re convinced their heart is killing them from the inside, they close their eyes, perform breathing exercises, repeat a mantra or act out other behaviors they’ve practiced, in the hope of pulling themselves out of the harrowing depths of a panic attack.

But for people who live with cardiophobia, the reassurance they’ve received from medical specialists that their heart is working the way it should just isn’t enough to calm their minds. Their particular anxiety disorder spirals them quickly down a rabbit hole of terrifying thoughts that say they’re definitely dying from a heart attack. There are physical symptoms, but they’re all manifestations of panic. Even though this may have happened dozens of times before, and doctors have told them their heart is in good health, they’re convinced it’s failing to function. Knowing what health professionals will tell them, they seek other diagnostic means, which demand time and money.

Earlier this month, Ireland Baldwin, the actor/model/writer daughter of Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger, revealed on Instagram that she lives with this little-known condition. Holding up a blood pressure meter in one photo, and nuzzling up against it in the next, Baldwin posted that she “suffers with anxiety and anxiety disorders,” including cardiophobia.

“I ordered a blood pressure monitor to accurately read my heart rate and blood pressure because I live in a constant fear that I’m dying from a heart attack,” she wrote. “The heart palpitations and chest pain brought on by your typical anxiety attack convinces me that I am a 26 year old with an underlying heart condition that I don’t have.”

Her social media post racked up more than 22,000 likes and earned some media attention. Many of the post’s commenters thanked Baldwin for raising awareness of the issue, and said it helped them realize they are not the only ones living with cardiophobia.

“This is not a new phenomenon,” says Dr. Andrea Ross, a core faculty member and assistant clinical director at the University of Phoenix’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Ross has treated clients with cardiophobia at her private mental health counseling practice, and she praises Baldwin for giving the condition more widespread attention. “It can save people some time and money,” Ross says. Instead of believing they’re having another heart attack, people with cardiophobia can seek more appropriate treatment sooner, Ross adds. “It can save that financial burden on that family, but also our medical facilities.”

Cardiophobia affects hundreds of thousands of Americans. In many cases, Ross says, the condition stems from general worries and feelings of a lack of control. Ross also reports that cardiophobia is found more often in relatively young people than those in older age brackets, who are more legitimately at risk for a heart attack. Ironic, yes, but this is attributed to the fact that cardiophobia frequently arrives as a response to a cardiac-related traumatic event, like the death of a parent by heart attack. The cardiophobe is then fixated on supposed genetic predispositions that could cause them heart problems. And although heart disease adversely affects men at a much higher frequency than women, Ross says research shows cardiophobia is found in men and women at roughly the same rate.

Among other effects, cardiophobia can generate depression in people because they feel like they can’t engage in any physical activity for risk of a cardiac event. The impact of cardiophobia can be so overwhelming for a person that it can even spur suicidal thoughts and attempts.

A 21-year-old college student in Oregon named Bailey Jørgensen writes in an email that she nearly took her own life after becoming so worried about her heart health. She dropped out of school, quit her job and moved back in with her parents. Like many people with cardiophobia (and other anxiety issues), she struggles with additional mental health conditions, including chronic depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. In March 2020, she says, she experienced “a common palpitation called a premature ventricular contraction.”

“At the time I had no idea what it was and thought my heart was going to stop,” Jørgensen says. Her cardiophobia had been triggered.

On a daily basis, she says, she began experiencing a series of irregular heart rhythms, all of which she refers to by scientific titles — “premature atrial contractions, runs of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, non sustained ventricular tachycardia, and phantom ectopics” — indicative of the gobs of time she must have spent researching cardiac issues.

“I became aware of my heartbeat at all moments,” Jørgensen says. “I also began to avoid any kind of exercise because of how uncomfortable my heartbeat made me. I was averaging about an hour of sleep a night. It became so bad that I went almost an entire week without sleep and had to be hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital and heavily sedated for about a month.”

There were also five trips to the emergency room and repeated visits to a cardiologist and an electrophysiologist. Her cardiologist was “dismissive of my fears because I am so young,” Jørgensen says, and the electrophysiologist told her “he didn’t want to see me in his office again.”

Ross says that cognitive behavioral therapy — a type of therapy aimed at cognitive distortions that works to change the way a person thinks and copes with challenging situations — is a go-to treatment for cardiophobia. Identifying triggers (sometimes through journaling) also helps the patient, giving them a sense of empowerment while helping them understand that they’re experiencing anxiety during these stressful moments, not cardiac arrest.

Exposure therapy is also an option. For example: If a person with cardiophobia fears physical activity, they might try walking around the block in which they live.

“If they can do this and not die, it adds to their experience, something to contradict or to challenge their anxious thoughts,” Ross says.

Jørgensen says her treatment has been heavy on exposure therapy. These days, she’s back in school and better managing her anxiety. She still has moments where she fears her heart is giving out on her, but “for a while, I didn’t see how it would be possible for me to live with that fear forever,” she writes. “Now, I have a much better outlook on the future.”

People can indeed suffer and die from a a heart attack as a young adult. However, out-of-the-blue cardiac events are extremely rare, says Dr. Raelene Brooks, another faculty member at the University of Phoenix, where she is dean of the College of Nursing. In her 17 years as a cardiovascular ICU and trauma nurse, Brooks says she witnessed many individuals come through a hospital believing they were having a heart attack, when the episode was in fact panic-induced. If a person is experiencing the classic symptoms of a heart attack, and there’s a medical history of high cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, or heart conditions, including a ventricular septal defect (a hole in the heart), a mitral valve or an aortic valve issue, and dysrhythmia, among other problems, Brooks says they should immediately seek medical attention. (She also adds that excessive use of illicit stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine can cause a heart attack in an otherwise healthy person.) However, if none of those comorbidities are known, most of which come about in old age or are typically diagnosed by pediatricians, chances are the chest pressure they’re feeling is the sign of a panic attack, not a heart attack.

Another indicator that a panic attack is occurring is the longevity of the symptoms. Panic attacks generally subside within a half hour; heart attacks go on longer and symptoms can worsen.

Brooks points out that when a person has a heart attack, rest can make the symptoms disappear, if only temporarily. “Because when the heart is at rest it’s getting more blood flow through it, more oxygen,” she says, “and therefore the pain tends to subside, and then when they pick up with activity again, or stand up or walk a few feet, it will rise again.” But when panic-attack symptoms are not immediately treated, they’re more “consistent and constant,” she says.

It’s understandable that a person having chest pain or pressure, sweats and an irregular heartbeat might seek a hospital stay for a suspected heart attack. Even if they’re relatively young, and especially if they haven’t received mental health treatment in the past that would make them more aware of panic attack possibilities. A visit to a mental health specialist, however, can be a first step in dealing with any lingering fears of a heart attack, before cardiophobia really takes hold.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.