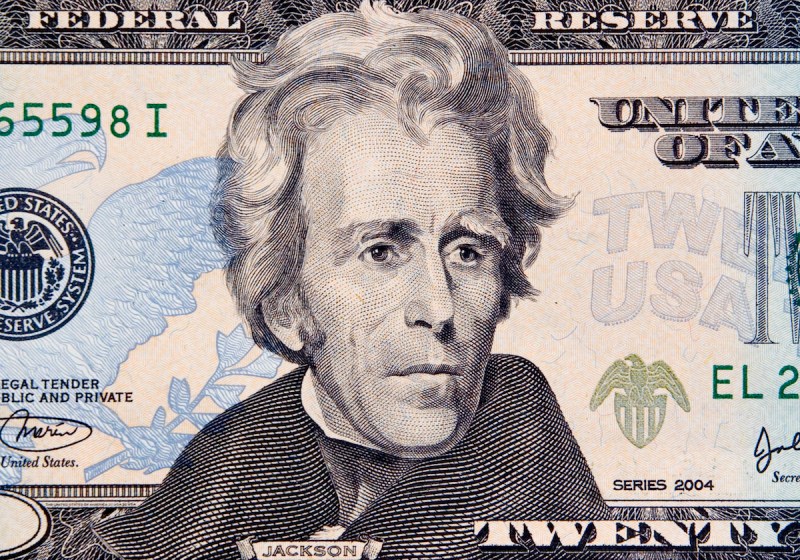

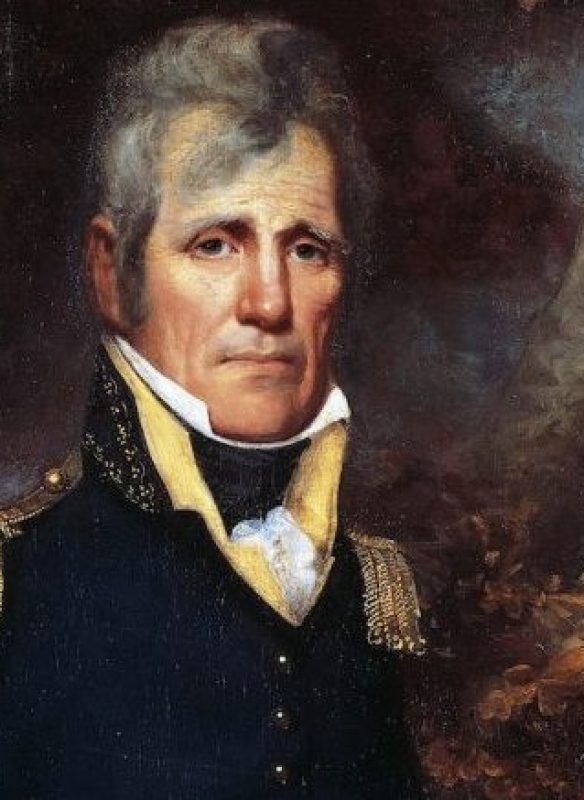

President Donald Trump has a complicated relationship with Wall Street. On the one hand, the stock market has hit record levels and no one seems to be employing more Goldman Sachs execs than the Trump administration (besides, of course, Goldman Sachs itself). On the other hand, Trump has called for extremely protectionist policies. Typically, Wall Street wants free trade whenever possible. Will there be a showdown? Whatever happens is bound to be more civil than the war between President Andrew Jackson and the Bank of the United States. This showdown that never needed to occur rocked America’s financial system and created a very new sort of economy.

To begin, it’s necessary to understand how, shall we say, flexible credit was in America during the 1800s. Daniel Feller revisited this time period for Humanities. He writes:

“The connection of banks and government was fraught with financial and political peril, especially in a young republic whose citizens craved riches and yet resented every hint of aristocratic privilege. Banking was poorly understood, not yet professionalized, and its amateur practitioners sometimes wreaked disaster on their customers. Indeed, men commonly sought bank charters not as an outlet for investment, but as a source of credit—not looking to lend, but to borrow. In a financial sleight of hand, the required paid-in capital to start a bank often consisted of IOUs to be redeemed by the bank’s own profits.”

In 1828, General Andrew Jackson had at last become president. (He had previously lost to John Quincy Adams despite receiving more popular and Electoral College votes in the “Corrupt Bargain” 0f 1824.) The Bank was, at the time, America’s only financial institution with a national reach. While it was not up for renewal until 1836, its president Nicholas Biddle pressed for Jackson to do so ahead of schedule. (Which would provide a boost to its stock price.) In return, he offered to have the bank assume the last of the national debt. Seemingly, all parties would benefit.

In Jackson, however, he had encountered a man who already believed himself to have been wronged by the nation’s elites. Now he felt another corrupt bargain was being offered. Jackson instead lashed out at the bank publicly. He asserted that the bank was unconstitutional and, indeed, a threat to our liberty. It was a particularly bold move because the bank was one of America’s few financial institutions with a credible reputation, whose notes actually retained their value.

Neither Jackson nor Biddle would back down. The bank’s charter came up for renewal ahead of schedule in 1832, winning the approval of Congress. Then Jackson dealt out an authoritative veto, announcing: “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.”

Biddle’s supporters lacked the votes to override the veto, but the bank still would exist until its previous charter expired. Jackson tried to speed up its downfall by withdrawing government deposits. Meanwhile, Biddle limited loans, in an attempt to shake the economy and scare people into supporting the bank. It did cause economic harm, but the Bank of the United States would never be the same, ultimately becoming a state institution with a Pennsylvania charter. Ripple effects were felt for years to come. Many blame Jackson’s destruction of the bank with triggering a speculative bubble and, after he left office, economic crash in 1837.

Of course, first the necessities of fighting the Civil War and then the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 ultimately nationalized banking again, meaning President Andrew Jackson’s controversial, hard-fought victory was a temporary one.

—RealClearLife Staff

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.