The remaining family had been bound and beaten to death, and two of the children were gone. In the small, remote house in Coeur d’Alene Idaho lay the bodies of Brenda Groene, Mark McKenzie, and 13-year-old Slade Groene. Dylan, age 9, and five-year-old Shasta were nowhere in sight.

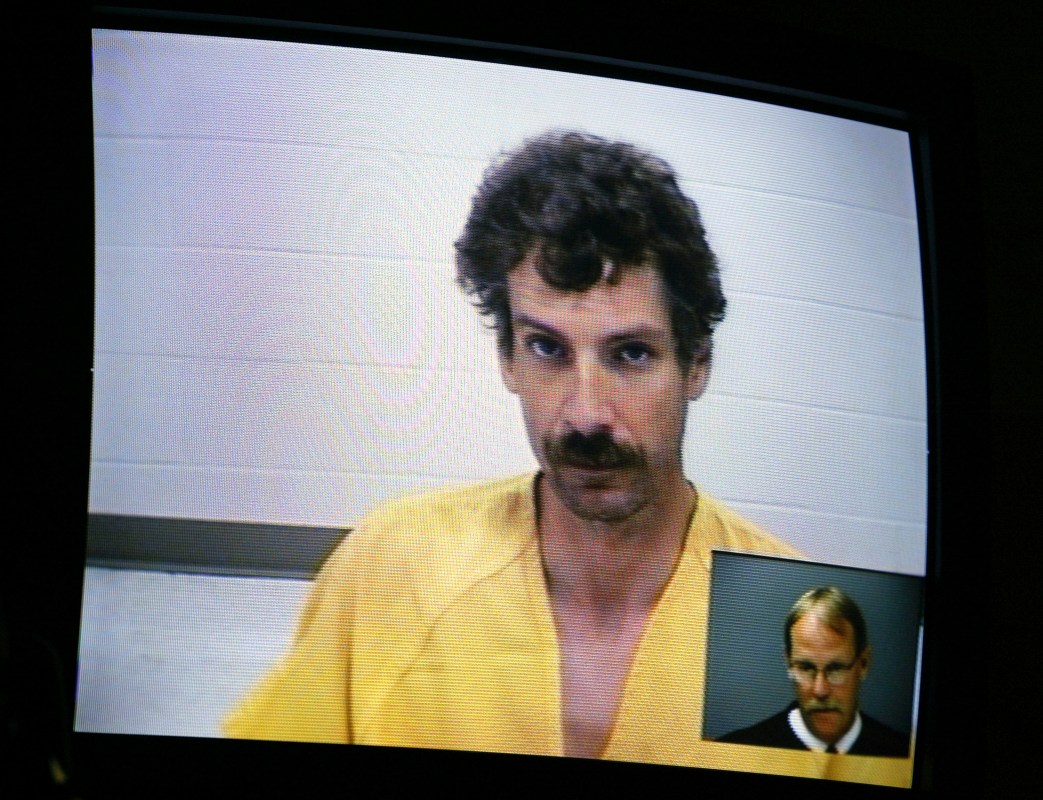

The monster who killed the three inside the house had taken the children. He was a level III sex offender who had spent much of his life in prison and who would later be revealed as a serial child killer. His name was Joseph Edward Duncan III, and strangely—for a man who had every reason to conceal himself—he was a prolific and revealing blogger.

Duncan was a creature of the internet. He kept his blog as well as a standalone website and a lightly-used YouTube account (see one of his videos below). His online life was an integral part of his identity when he went to ground in the spring of 2005—about a month before he attacked the Groenes.

That life wouldn’t come to light until he was arrested in Coeur d’Alene in July that year. He’d repeatedly raped the kidnapped children before killing Dylan Groene. Shasta was still alive, but she’d suffered unspeakable trauma.

Duncan wasn’t the first homicidal psychopath to build a website or blog, but he may have been one of the most prolific.

As the internet grew and morphed over time, blogs giving way to social media, there would be many more. They would sometimes demonstrate that those with twisted minds didn’t really bother hiding who they were. They would also show that occasionally, a killer’s internet profile just isn’t that different from anyone else’s.

Duncan called his blog “The Fifth Nail.” It looked like a prototypical Blogger-hosted site, until you read the “about,” which revealed his narcissistic belief in his martyrdom. He wrote about a myth that “gypsies” made “(sic) five nails for Christ’s execution not four. The fifth nail was meant to pierce his heart, but the gypsies hid the fifth nail from the roman soldiers. In some stories the gypsies were punished by God for prolonging Christ’s suffering (…) Its existence today is somewhat questionable, unless you consider the metaphor.”

Duncan was a diligent blogger. Many of his posts dealt with issues that seemed particularly personal—like this one, which simply read, “The only cure for crime is Love. Everything else is just more crime.”

Others revealed grievances. Duncan had many, and this post from December 2004 was pretty typical. He titled it “You don’t know what fed up is…” and wrote that he would only call 911 if he knew failing to do so meant he “would go to jail for not reporting a crime.” He insisted this wasn’t empty talk. “I know how to protect myself,” he wrote, “and can think for myself as well. Does that make me a ‘threat to society.’ The police are supposed to be providing a valuable service to our communities, when instead they are weakening your minds so you will depend on them more, and pay your taxes, so they can ‘protect you’ from things you should damn well know how to protect yourself from!”

When blogs, websites, and social media profiles created by criminal suspects and crime victims began entering the news, they were novel enough. Critics of linking an accused killer’s blog or a murder victim’s Myspace pointed out that in the former case, they didn’t necessarily reveal anything telling or interesting. In the latter, the practice was invasive, crass.

As for the value of examining the internet presence of anyone accused of a crime, there was some truth in the assertion that it wasn’t always easy to find any tell-tale signs something was wrong.

Kevin Underwood was 26 in 2006 and his main online presence was, like Duncan’s, a Blogger-hosted site, FutureWorldruler.blogspot.com. There wasn’t anything overtly alarming about it. For example, in a post written in 2003 Underwood filled out one of those random, tiresome quizzes your most annoying friends pass around on Facebook today. Just a few of his answers reveal how innocuous he seemed:

“last weird encounter: Any time I see my sister.

last ice cream eaten: Chocolate frozen yogurt at work, and that’s been a couple of months ago.

last time amused: Almost constantly.

last time wanting to die: Many months ago.”

In April of 2006, Underwood was arrested and charged with the kidnapping and murder of 10-year-old Jamie Rose Bolin. He’d bludgeoned her to death with the intent of eating her. While Underwood had also mentioned depression as well as “dangerous” fantasies, no one reading his posts before his arrest would have found reason for serious concern.

Ben Fawley was in his late 30s but looked—and acted—much younger. He had an online presence that Peter Pan would love. He’d been creating websites since the 1990s, using do-it-yourself services like Geocities. All were partly dedicated to furthering his image as an overgrown goth skater boy. Many online records of Fawley’s work aren’t easy to find or are gutted today, but he had at least one Livejournal. In it he took the prosaic quizzes like Kevin Underwood—and some mentioned an LJ friend, screen name tiabliaj.

“Tiabliaj” was a college freshman named Taylor Behl.

Fawley was arrested for the murder of Taylor Behl in 2005, and he was eventually sentenced to 30 years in prison. He submitted an Alford Plea—meaning he didn’t plead guilty but acknowledged the court had enough evidence to prove his guilt.

Among that evidence was a photograph of a broken-down shack which he’d sarcastically captioned “Home Sweet Home.”

It was made near the home of Fawley’s ex, Erin Crabill, and not far from where police eventually found Taylor Behl’s remains.

A comprehensive list of online media created by convicted killers or even serial killers would take weeks to compile and would probably fill an entire digital book. Many weren’t as chilling as Duncan’s, as weird as Fawley’s, or as ironically plain as Underwood’s. Sometimes, a blog can be a boring digital mask hiding a nightmare.

Outwardly, Lacey Spears was an optimistic mommy blogger. Her little-used BlogSpot titled “Garnett’s Journey” had a sunny design and featured her son, Garnett Paul. The long-haired boy looked happy enough in photographs, and in a Twitter account, Spears repeatedly expressed her undying affection for her sickly child, who endured constant doctor’s visits and trips to the ER.

This theme continued on her Myspace account and various message boards where many found her sympathetic—until she was arrested for killing Garnett with an overdose of salt. It’s been theorized she suffered from Munchausen’s by Proxy—seeking attention through making her child sick. Whatever she had, she’s got 20 years in prison to think about it.

Raven Abaroa walked out of jail in late 2017, a free man. He’d been in prison since 2014, having entered an Alford Plea in the 2005 death of his wife Janet. She’d been found stabbed to death and though he was an immediate person of interest, Abaroa wasn’t arrested till 2010.

The Alford Plea led to a manslaughter conviction, hence the short sentence. Abaroa had originally been charged with first-degree murder.

Like Lacey Spears, Abaroa had a mostly unremarkable web presence. His main website was RavensTree.com. It was about his car, money, his son, and himself—with incidental mentions of his wife. Still, if narcissism was evidence of murder, plenty of other young men would be in prison today; any odd notes in Abaroa’s online life only seem odd in hindsight. That’s often the case.

For example, Vester Flanagan—a.k.a. newsman Bryce Williams—had a typical news guy’s Twitter account for a while. Okay, it was a little more vain than usual. He tweeted about his family, his apartment, and mostly about himself. It was typical social media narcissism, though, not threatening. Until August 26, 2015, that is. That was when he shot reporter Alison Parker and cameraman Adam Ward on-air while recording the murders from his own point-of-view. Afterward, he tweeted that “Alison made racist comments” and “Adam went to hr on me after working with me one time!!!”

He followed that up with a tweet indicating he’d “filmed” the whole thing, directing readers to Facebook. The video, which has been taken down, was utterly harrowing.

Flanagan committed suicide later that day.

The ultimate example of a homicidal psychopath with a completely innocuous website: a serial killer who left a trail of death across the nation before his suicide in 2011. Israel Keyes may have murdered dozens, combining both sniper-style attacks and horrifying nighttime home invasions. His only obvious web presence: a page he created for his construction business.

He charged perfectly reasonable prices.

In his last post before his final spree, Joseph Edward Duncan wrote, “My blog entries lately are erratic and full of a lot of B.S., for that I apologize.” He went on to describe his chaotic state of mind and sense of confusion, as well as his “demons.”

Then he wrote, “I wish I could be more honest about my feelings, but those demons made sure I’d never be able to do that. I might not know if it matters, but just in case, I am working on an encrypted journal that is hundreds of times more frank than this blog could ever be (that’s why I keep it encrypted). I figure in 30 years or more we will have the technology to easily crack the encryption (currently very un-crackable, PGP) and then the world will know who I really was, and what I really did, and what I really thought.”

As intriguing and deeply unsettling as Duncan’s blog is, it may not be nearly as important as that encrypted journal—if it exists.

That’s the thing about all these instances of twisted minds expressing themselves online: In the end, what they’re hiding is far more important than a blog post, a tweet, or a Facebook status.

It could also be much more dangerous.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.