Any unsolved crime is intriguing enough, but some surpass conventional intrigue and fall into the realm of the strange. I’m not talking about merely weird; I mean truly creepy, the kinds of crimes that could have an armchair sleuth up all night, obsessed with a solution.

The internet loves lists, so it abounds with rundowns of unsolved homicides. Some of the following might be familiar to anyone who’s ever read one of those lists—some won’t. Some are also obviously crimes. Others are assumed to be homicides, because—at least in one case—there’s really no other rational conclusion.

You won’t find “classic” unsolved cases here: No Jack the Ripper, no Zodiac, no Black Dahlia. Some of these are the cases you’ve never heard of.

These are in no particular order—they’re all equally intriguing in their own ways.

Who Put Bella Down the Wych Elm?

Driving along the A456 (Hagley Road) between Central Birmingham and Woofferton, Shropshire you’ll pass the border of Hagley Wood. From the road, it looks forbidding. It’s easy to think of a gothic heroine trapped in the shadows of the trees as dark falls, misty and menacing. Naturally, it’s home to a mystery that’s endured since the early 1940s.

On April 18, 1943, three boys hunting birds’ nests spotted an enticing Wych elm—one of the most common breeds of European elm tree. The tree’s wide trunk was virtually hollow, and as one boy climbed he looked down and through a knothole he saw a skull, hair attached to the skull, and inarguably human teeth. Someone’s body had been stuffed inside the tree.

The boys didn’t notify police right away; they’d been trespassing. Finally, one did.

Along with the skull, investigators found most of a skeleton, a wedding ring, and a shoe. In the skull’s mouth, they found crumpled taffeta. Forensic investigation revealed she’d been smothered then hidden inside the tree almost immediately after death.

Bella Thorne’s skull.

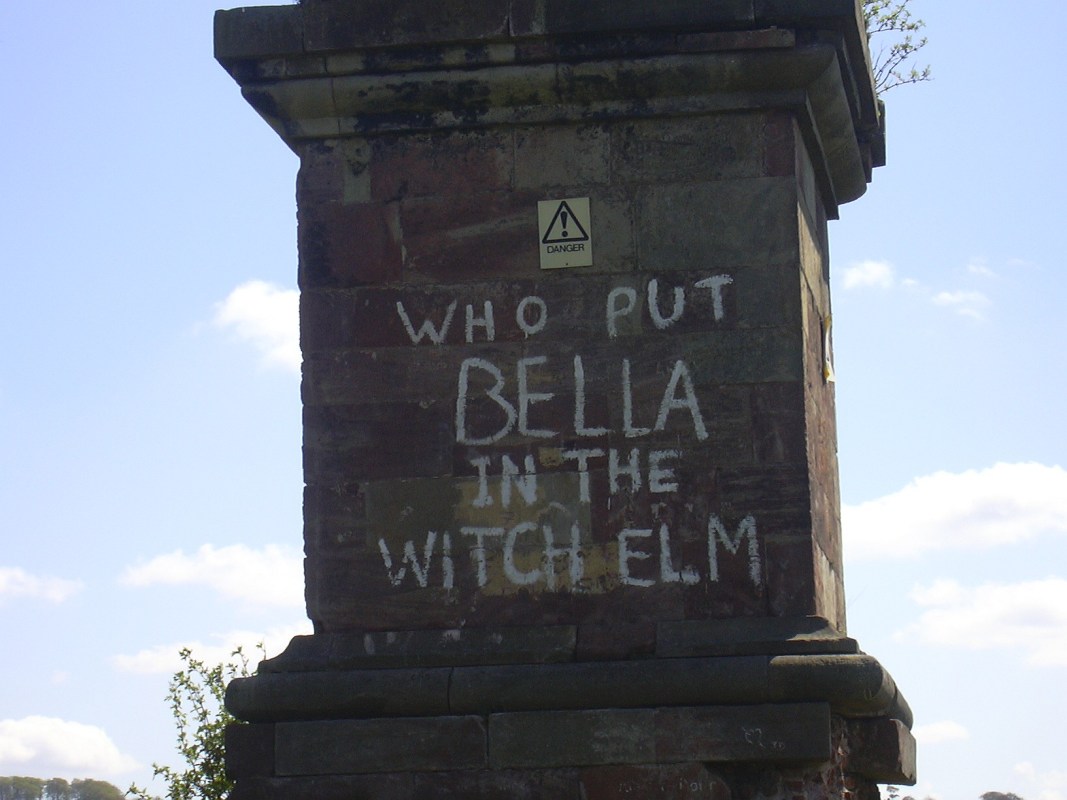

In 1944 someone scrawled graffiti on a wall in Birmingham: “Who put Bella down the Wych Elm – Hagley Wood.”

The same question has appeared over and over again —often written as “Who put Bella in the Wych Elm” since the 1970s on the side of an obelisk not far from the site.

In the forties, one theory suggested witches sacrificed Bella in a ritual. It was wartime, so it was possible she was a spy or a woman who knew too much. But to this day, no one really knows.

The Springfield 3.

On June 6, 1992, the Springfield, MO News-Leader predicted partly cloudy conditions that night with lows in the sixties. Suzanne Streeter and Stacy McCall had just graduated from high school and they’d been at a party till just after 2 a.m. when they headed into the cool night for Suzanne’s home on 1717 E. Delmar.

Stacy, Suzanne, and Suzanne’s mother Sherrill Levitt were never seen again.

The disappearance of one person might be intentional. Maybe they just wanted to begin a new life. The disappearance of two teenage girls and one girl’s mother is obviously something else altogether.

It was obvious from the beginning that whatever happened probably happened fast. There were no signs of struggle, yet everything someone might take with them was still there—purses, clothes, cars, cigarettes, and Levitt’s and Streeter’s dog.

The last anyone heard from Levitt was a phone call around 11 p.m. the night of the 6th. She was likely asleep before she and the girls left, as it was obvious she’d gotten out of bed. So, the trio vanished into the night sometime after 2 a.m.

There’s a $42,000 reward for any information that leads to finding whoever kidnapped Sherrill, Suzanne, and Stacy.

The Oakland County Child Killer

Oakland County child killer profile.

It’s possible the child killer—or killers—who murdered Mark Stebbins, Jill Robinson, Kristine Mihelich, and Timothy King was identified. While little about this unsolved series of murders which occurred between February 1976 and March 1977 resembles the infamous Zodiac murders, it is similar in that there were several suspects over time. They included known pedophiles, a mysterious male couple in which the sub claimed his dom committed the crimes, and John Wayne Gacy.

One strong suspect, Chris Busch, committed suicide in 1978, and no murders matching the Oakland County profile ever happened again. But the case is considered unsolved.

And the details are haunting.

The children were all held for days, even weeks. They were bound and sexually tortured. The final confirmed victim, Timothy King, was held from March 16, 1977, till March 22. During that time his mother wrote a letter to the Detroit News saying she wanted him to come home soon so he could have his favorite food, Kentucky Fried Chicken.

When Timothy was found, he was posed with his skateboard next to his body. His clothes had been washed and pressed.

An autopsy indicated his final meal was fried chicken.

The Villisca Ax Murders.

In 2017 Bill James and his daughter Rachel McCarthy James published The Man From the Train. The Jameses claimed they’d solved the mystery of the June 10, 1912, murders of the Moore family and two guests in Villisca, Iowa. They identified a man named Paul Mueller and laid out a case for Mueller having ranged across the US and into Canada, killing up to 100.

While the authors made a compelling case, the truth is that after 106 years, the case will never be solved.

The details of the Moore murders are horrific and strange, and perhaps more bizarre still for where they occurred: a sleepy town in the southwest corner of Iowa with a population of just over 1100.

The night of June 9, 43-year-old Josiah Moore, wife Sarah and their children Herman, Mary Katherine, Arthur, and Paul, headed home from Children’s’ Day events at their church. With them were Mary Katherine’s friends Ina Mae and Lena Stillinger.

Someone was waiting for the group in the attic of the Moore home at 508 E 2nd St. He’d smoked a couple of cigarettes as he waited. Then sometime between midnight and 5 a.m., he killed everyone in the house with Josiah’s own ax. He used the blunt edge on everyone save Josiah, who received more blows than anyone.

A slab of uncooked pork sat beside the ax in the guest room where the Stillingers were killed. All the curtains in the house were closed.

The Texarkana Moonlight Murders

Long before the Zodiac Killer, another nameless psychopath preyed on couples parking in out of the way places around Texarkana, a city that sits on the Arkansas-Texas border.

Over the course of ten weeks, five people were killed. Some of the women were sexually molested, one man was beaten. All were shot. Then the murders simply ceased. Three more victims survived the “Phantom Killer’s” attacks. Descriptions of the killer were consistent: he wore a white mask, holes cut for the eyes.

A convincing case has been made through the years that the killer was a habitual criminal named Youell Swinney. His wife even said he did it, only to later recant. Swinney died in 1994, taking whatever secrets he had with him

That fall night in Palo Alto, Arlis Perry was just 19 and married to Bruce Perry, whom she’d met in high school. Bruce was a sophomore at Stanford, Arlis, a receptionist.

The story of that night—October 12, 1974—goes from merely odd to a surreal nightmare.

Bruce said they’d argued, then Arlis left, saying she wanted to pray alone at Stanford Memorial Church.

In the middle of the night, a worried Bruce called the police to report that Arlis hadn’t come home and told them where she was. When they checked, the church was locked, and everything looked fine. A few hours later a security guard entered the church and found Arlis on the floor, not far from the altar.

She lay on her back, a 5-inch-long icepick jutting from her head. She’d been strangled. A large candle lay on her chest. She was nude from the waist down and a second candle had been inserted in her vagina.

Of the people who were in and out of the church that night, one was never identified—and the resemblance between that unknown man and a strange visitor to Arlis’s workplace on October 11th was significant. Bruce Perry was quickly ruled out.

While no less than Son of Sam serial killer David Berkowitz claimed some kind of knowledge of the case, investigators concluded he had no involvement.

Theories have frequently included some kind of Satanic ritual, which in this case sounds logical. A religious group with tentative links to Charles Manson was considered as well. But no one knows what really happened that night, save that it was the stuff of horror films.

If you ever watched Unsolved Mysteries in the 1990s, you may be familiar with the unsolved murder of Blair Adams. It’s damn hard to forget.

On July 11, 1996, Blair was found dead in a hotel parking lot in Knoxville, Tennessee. Almost $4000 in cash was flapping and flying around him. It was an odd mix of currencies; bills from his native Canada, American dollars, and German Deutschmarks.

Before his death, Blair seemed like a man on the verge of a meltdown. He was paranoid, telling people close to him that someone wanted him dead. He had mood swings similar to typical bipolar disorder.

He withdrew the money from his bank on July 5 and added expensive jewelry to the mix. He then attempted to cross into America but was halted—that much cash spelled drug mule to border patrol. He rerouted and bought a plane ticket to Germany—which he didn’t use. Instead, Blair made another run at a border crossing and succeeded in crossing into Seattle.

Blair made another weird move and flew to DC, where he rented a car and made his way to Knoxville. Witnesses said he seemed unnerved, like a man in crisis—psychological, real, who knows?

We know that Blair was murdered sometime around 3 a.m., possibly by a club. Something heavy enough to kill.

Blair Adams’s murder is the coldest of cold cases now. Even though police found hair from someone else in his hand and managed to mine it for DNA, there was never a match. We just have a man far from home, dead in the night, all the answers went with him.

On February 13, 2017, Liberty “Libby” German, age 14, and her 13-year-old friend Abigail Williams managed to photograph then record the voice of their killer. Yet over a year after the double homicide in Delphi, Indiana, the case remains unsolved.

The girls were on the Delphi Historic Trails, doing what 8th graders do, snapping pics, posting them on social media. At some point, they must have noticed a heavyset man nearby. Libby had the presence of mind to take his photo. His head was bent, he was wearing a cap, walking with his hands in his pockets.

Once he was close enough, German caught one more clue: a man’s voice, tone flat, saying “Down the hill.”

Sometime after that, she and Abigail were murdered.

Police have released very little about the investigation. They’ve said they have DNA, and more than once indicated they felt very close to solving the mystery. Daniel Nations, a man arrested in Colorado, has been mentioned as a person of interest, but he’s never been arrested.

What’s left as of March 2018 are just the threads of a mystery that seems so close to a solution, but it isn’t there. At least—unlike many of these cases—there’s still plenty of time to figure it out.

From the late 1960s through 1985 or so, someone murdered at least 14 people in and around the Florence, Italy. The case is famous, in part due to its resemblance to the Zodiac murders in Northern California in 1968-69.

Il Mostro, as Italians called him, targeted couples parking on lovers’ lanes. He killed with a .22 and a knife and added a gruesome signature: cutting off parts of the women he murdered as souvenirs. He may have also stalked some victims prior to the murders and taunted their families after.

Police didn’t lack for suspects, the most noted being convicted murderer and “Peeping Tom” Pietro Pacciani. In fact, Pacciani stood trial for Il Mostro’s crimes and was convicted—only to have the conviction overturned. Then Pacciani’s friends Mario Vanni and Giancarlo Lotti were convicted of the murders and imprisoned—but few Italians are convinced they collaborated on the crimes.

Theories about the case such as some kind of satanic link (a common suggestion regarding unusually strange murders) abound, but there is a powerful feeling among many Italians still that they don’t really know the answers to this mystery at all.

One of the chief reasons you haven’t heard of the Freeway Phantom—a truly creepy killer who forced a victim to write a taunting note to police—might well be racism.

Between 1971 and 1972 the Phantom murdered six young African-American women in and around Washington DC. They were between 10 and 18 years old. Some were sexually assaulted.

His spree began in April of 71 with Carol Spinks, age 13. She disappeared while walking home after buying groceries. Her body was found almost a week later in the grass not far from I-295. Then in July, the killer took 16-year-old Darlenia Johnson. She was held for just over two weeks before the Phantom dumped her body just feet away from where Carol Spinks was found.

The killer next took 10-year-old Brenda Crockett. A few hours after she disappeared she called home, crying. She said a white man had picked her up and she was coming home—then ended the call suddenly with “Bye.” Brenda called back, saying she was in a house, and once more was yanked off the phone.

Unlike the others, she wasn’t held. The killer raped and strangled the girl to death before dumping her by the side of a Maryland highway. Nenomoshia Yates was next. She was just 12 and she suffered an almost identical fate to Brenda Crockett, including being found beside the road.

The killer earned the “Freeway Phantom” moniker after Nenomoshia’s murder. The Phantom wasn’t done. His most bizarre murder was next.

He abducted Brenda Woodward, an 18-year-old who was last seen getting on a bus to go home. When she was found several hours later, she lay under her own coat. The killer left a note this time, and the police believe he made Woodward write it: “This is tantamount to my [insensitivity] to people especially women. I will admit the others when you catch me if you can! Free-way Phantom.”

Final victim Diane Williams was 17 and she too was abducted after boarding a bus, only to be found strangled and dumped by I-295.

Police believe Brenda Crockett was forced to lie when she made her haunting phone calls.

A local gang was suspected of some connection to the murders and a prison inmate claimed knowledge then clammed up. In the end, the police files were lost, and all the threads left dangling. Six girls dead by the road at the hands of a psychopath who then vanished—in part because police of the era couldn’t be bothered to hang on to evidence.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.