Since its (re)launch in 2014 — and the release of its first product (rye) in 2017 — Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co. has racked up pretty much every major whiskey honor: It was ranked as the top American rye by Whisky Advocate, championed as the Global Craft Producer of the Year by Whisky magazine (beating out literally thousands of distilleries) and even swept a National Association of Container Distributors ceremony, thanks to the distillery’s distinctive and very heavy bottle design.

And hey, we even named Peerless our favorite American whiskey back in 2019.

But even our admiration was tempered by some confusion regarding Peerless’s legacy. The brand seemingly falls under a lot of typical whiskey tropes, from multi-generational ownership to a history littered with Prohibition-era tall tales.

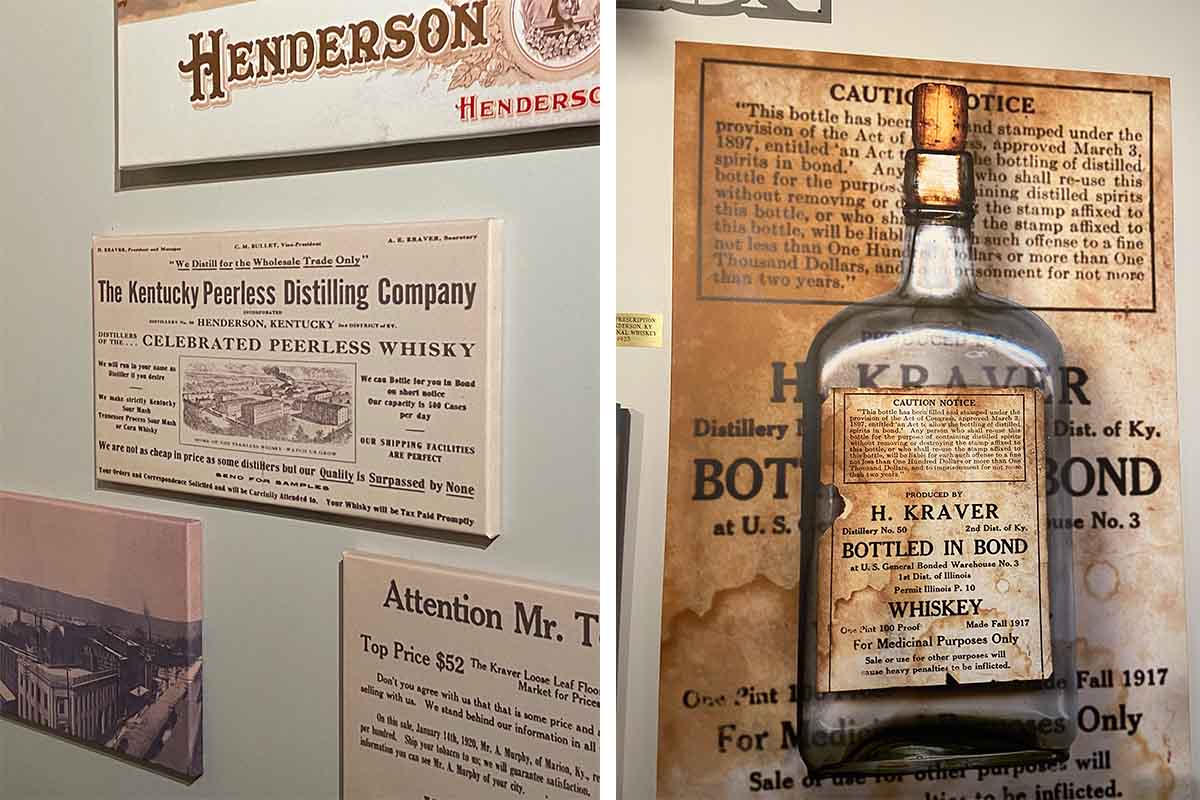

And yet, Peerless today is almost nothing like the product you’d experience from Henry Kraver when he bought the fledgling E.W. Worsham & Co. Operations in Henderson, KY, in the late 1880s.

While a tour of Peerless’s new-ish facility in downtown Louisville is filled with stories and artifacts over 100 years old, Peerless in 2021 is a very modern operation with some unusual and exciting methods for producing ryes and bourbons that bely their short aging process — those first award-winning ryes featured a shocking minimum of two years of barrel maturation.

And speaking of low aging — having Kentucky’s youngest Master Distiller, not yet 30 (and not part of the Peerless bloodline), brings a valuable new perspective to the world of American whiskey.

So we took a three-day trip down to the distillery to meet the team, try Peerless’s newest release just as its first bottle went up for auction and decipher a whiskey legacy that stretches back to the 1880s but is very much about the here and now.

Here’s what we learned.

One number is more important to Peerless than anything else

No, not their mashbill (those numbers are kept secret). You’ll see the same two digits almost everywhere you step or look when you enter the Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co. building in downtown Lousiville, located two blocks down from the Louisville Slugger Museum on a somewhat desolate strip off Main on North 10th Street.

And that number is 50.

Specifically, the number is DSP-KY-50, which stands for the company’s Distilled Spirits Plant designation. Basically, having a number that low suggests exactly how important and special Peerless was to a growing and nascent whiskey industry in the 1800s. They were one of the first.

Distilleries launched in the United States today? Those DSPs get a number somewhere in the 20,000 range.

Interestingly, Peerless took a long hiatus (basically, from Prohibition times to 2014) but managed to get grandfathered in with that low DSP, a process that pretty much started and ended with the distillery’s return. Based on a letter Peerless received this year, any other distillery that even thinks about reviving an early spirits brand isn’t going to get a low number that corresponds to their distant past.

Their story isn’t exactly typical

Talk to Kraver’s great grandson, Corky Taylor, and at first he’ll hit a lot of notes that seem familiar with anyone who knows the colorful (and often embellished) world of American whiskey. Family business, five connected generations, a pause during Prohibition (along with some stories that involved hidden barrels and a government license to sell bourbon for “medicinal purposes”).

Whiskey 101. But dig into the details and you’ll find some unexpected treasures. “All this started with my great-grandfather, who looks like a banker — because that’s really what he was and wanted to be,” says the senior Taylor. “[Henry Kraver] was Polish and Jewish, and immigrated here with his family when he was 5.” Peerless was simply a small part of Kraver’s life, which included owning the Palmer House in Chicago — the longest-running hotel in the United States — while also sitting on the board of several Chicago banks and running various tobacco warehouses, construction companies and even a brewery.

As for the rest of those five generations? Not all of them were about whiskey — Corky’s dad “Ace” was General Patton’s right-hand man and a veteran of World War II, Korea and Vietnam. And Corky himself? He was in financial services, and brought Peerless back when he got bored of retired life. His tale isn’t about bootleggers or secret masbhills — talk with Corky, and he’ll more likely tell you about his early passion for surfing, or rooming with Duane and Gregg Allman while in military school.

And Corky’s son, Carson, was actually in the construction business before he switched over to spirits. His knowledge base was extremely beneficial — he helped design everything from the distillery’s layout to Peerless’ unique notched bottle.

Their whiskey is overseen by the youngest Master Distiller in Kentucky

Caleb Kilburn became Peerless’s Master Distiller at 27. He was born and raised on a dairy farm in Salt Lick, KY, and, unlike many legacy distillers, has no bloodline connection to Peerless. His M.O.? Learn from the best, but take what you want.

“Before I came here, I just shadowed different distilleries and basically cherry picked things I liked,” he says. “Some things we do are common, but some things are way out there.” Basically, with the nearby Louisville Slugger Museum in mind, you can say Peerless takes a lot of big swings. And this is where “sweet mash” comes in ….

Sweet mash is a fairly unusual way to produce whiskey

A standard in the whiskey industry, sour mashing is the process of adding a portion of a prior fermentation or spent batch into the next run. It’s done to regulate bacterial growth and ensure consistency. (Think of it like making sourdough bread.)

Very few recognizable distillers (we can think of two — Castle & Key and Wilderness Trail) opt for “sweet mash,” a difficult process that forgoes any previous spent mash and, additionally, requires a more sterile environment. “To do a sweet mash, we have to use fresh corn, rye, barley and water every single day,” says Carson, who credits the distillery’s computer system and controls for regulating the process (also, it’s pretty rare for a distillery to discuss their high tech methods).

In return for the extra effort, Peerless gets a more complex flavor profile they prefer (sweet, floral, grassy) and “there’s no sour grain note you need to clean up,” as Caleb notes.

Bonus: Thanks to these additional sterile protocols, the facility (and the whiskey) is actually certified kosher by this guy.

They don’t do much with barrel finishes, but when they do …

You’re only going to find it at the distillery, but there’s a Peerless Rye release finished in barrels that previously held absinthe. It’s basically a herbaceous and spicy Sazerac in a bottle. You’ll either hate it or think it’s the most exciting thing ever. Depending on when we were drinking it, our opinion shifted between those two extremes.

Their Latest Release, Double Oak, Wasn’t Part of Their Original Plan

In the past years, a few barrels Peerless were using would fail (cracked stave, leak, whatever). So the distillery would put the maturing whiskey in a new barrel and mark it as double oaked. When they started doing picks for single barrel releases, they noticed a lot of these doubled-oaked barrels were imparting more interesting flavors.

“It was a happy accident, but the brings out other characteristics you’d never experience,” says Cordelle Lawrence, Director of Peerless’s Global Marketing & Strategy. “And now it’ll be an annual release.”

To make double oak part of a planned process, Peerless will have whiskey spend about four years in one barrel, and then a few months in a second. Again, the expected “wood” element you’d figure from this process isn’t that apparent — there’s a spiciness from the barrel, of course, but also cinnamon, honey, fruit and leather notes.

“Other distilleries that do this usually want to focus on the barrel, nothing else,” says Kilburn. “We wanted to be different.”

We got a chance to see the first bottle of Double Oak auctioned off during Kentucky Southern Social, a multi-day bourbon fest which featured small group dinners and events with top Kentucky distillers (Angel’s Envy, Woodford Reserve, Old Forester, etc.). The bottle fetched $1,500+ and came close to matching a bid made for some Pappy releases.

In the end, Peerless isn’t reinventing whiskey, but they’re certainly not beholden to liquids from a century past, even if those whiskies were an important part of the new distillery’s lineage (don’t bother trying to compare old and new bottles; few of the processes and none of the mashbills now will resemble anything Henry Kraver’s team did back in the early 1900s).

“Nothing we’re releasing is terribly exotic, and there are no secret ingredients,” says Kilburn. “It’s just a combination of things we like.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.