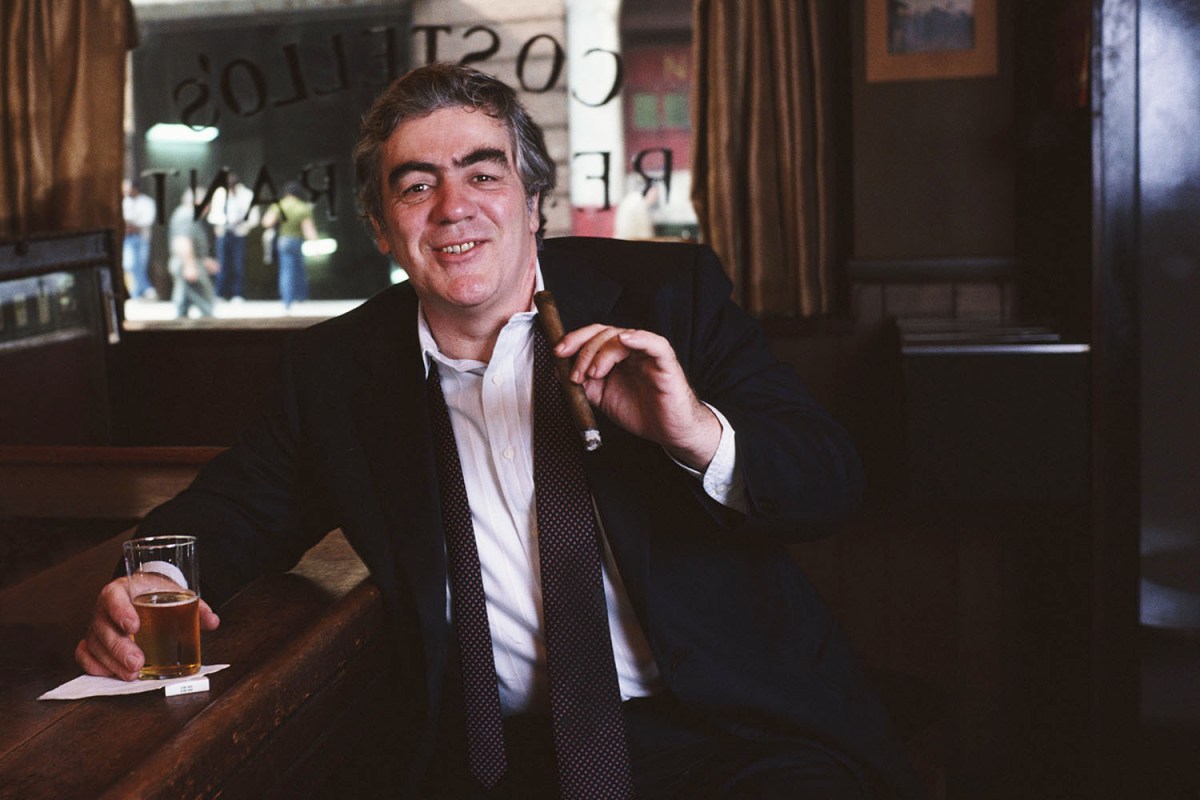

The smoky bar is packed with a typical after-work crowd. Drinking. Chatting. Big lapels and even bigger glasses. This is the 1970s, baby. One brash, heavyset man, the life of the party, two happy hour heroes hanging on his every word, turns to the camera. His black hair is unkempt, his black tie loosened, his pointed collars fly out of his too-small suit jacket. He holds a stubby bottle of beer in his meaty paw as he introduces himself:

“When Piels came to me to do this, I said, I’m not Bert or Harry, I’m Jimmy Breslin, a writer!”

How did it come to be that a slovenly newspaper reporter would become the star of a beer commercial? In many ways it’s the pinnacle of modern promotion, a hallowed genre that has given the world Spuds MacKenzie and the Clydesdales, Billy Dee Williams and the Swedish Bikini Team, the Wassup guys and the Most Interesting Man in the World. In this era when perhaps one-third of Americans think journalists are the “enemy of the people,” can you imagine one becoming so famous, so universally admired, that a brand would devote millions to him helming their precious beer spot?

Of, course, this was no ordinary writer — this was Jimmy Breslin, pugnacious New York City reporter, a “poetic and profane” journalist who always took the most unique angles whether writing about the deaths of JFK or John Lennon, or the lives of the downtrodden in his very own city. But, Breslin was also a man who wrote his own myths and willed himself into becoming larger than life, making the general public believe things about him that might not have even been true. But that didn’t matter, because one thing was very much true. As he notes in the commercial:

“Beer is not exactly a subject that is unknown to me.”

In the 1970s there really wasn’t craft beer, but there very much were regional lagers, unlike today. Pearl in Texas, Old Style in the Midwest, Olympia in the Pacific Northwest. Even Coors was a regional beer, mostly available in Colorado and the West (remember Smokey & the Bandit?)

Likewise there was Piel Bros. Beer, which was originally brewed by three German immigrant brothers in the East New York section of Brooklyn starting in the 1880s. The beer was beloved locally, so much so they were able to expand with additional breweries in Bushwick and on Staten Island.

In the 1950s, during the earliest days of beer advertising, the company found success with spots featuring two cartoon characters — the aforementioned Bert and Harry — who were the supposed owners of the brewery. This was really avant garde stuff back then, comedy bits instead of the hard-sell commercials of the day.

“We never thought we would see the day that viewers actually enjoyed watching a TV commercial,” noted Kay Gardella, The New York Daily News’ television columnist at the time.

But, by 1964 the characters were getting stale and Piels was facing an onslaught of competition from other local breweries like Ballantine, Rheingold and Schaefer, as well as some of the earliest national brands like Schlitz, Pabst and especially Budweiser, which had begun making inroads into New York City via relentless commercials. Piels knew they needed to pony up themselves, and decided to devote $2.5 million to a new ad campaign.

Enter Breslin.

Then 35 years old, The New York Herald Tribune reporter was already well-known for having written a unique piece about JFK’s gravedigger the year before and Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, a book chronicling the expansion New York Mets’ hapless first season in 1962. He was also well-known for hoisting pints and slugging whiskey at pubs around the five boroughs, places like Pep McGuire’s on Queens Boulevard, the Lion’s Head in Greenwich Village or his friend Mutchie’s saloon, Gallagher’s on West 52nd Street. Considering his reporting motto was “Keep your mouth shut,” when he was off the job and at the bar, Breslin was often doing most of the talking.

For Piels, Breslin would likewise appear in barroom settings, drinking beer and shooting the shit with real-life friends like heavyweight champ Rocky Marciano, best-selling pulp novelist Mickey Spillane and Pogo cartoonist Walter Kelly. Breslin hand-selected each of them, and talked his buddies into working for scale.

The advertising agency would film each duo talking, unscripted and off-the-cuff, for 30 minutes and then edit it down. (The one-minute spots seem to have been lost to the internet.) Starting in June of 1964, the spots would appear in eight northeastern markets that actually sold Piels: Hartford, Scranton, Syracuse and of course New York City.

“It’s a brand new way to merchandise beer and one that we think will be imitated by the other breweries,” John Brady, account supervisor on the campaign, told Sponsor, an ad industry periodical. “We thought that beer commercials were unreal, and presented non-beer users and scenes that were not beer situations.”

These commercials were extremely atypical for their time and confused many viewers due to their non-salesy presentation. In the spot with Marciano, for instance, the two men never even discuss their beer, instead arguing about whether boxers’ fists should legally be considered lethal weapons outside the ring. (Breslin: “If your fists are in your pocket, are they considered concealed weapons?”) Even if these commercials confused some, they were a big hit and cause Piels’s sales to boom in 1964, with that June being the biggest month in the brand’s entire history.

“He [Breslin] is a unique individual who cuts across all classes and is at ease with figures from all walks of life,” said Brady. “He also happens to be a Piels drinker who looks at home with a glass of beer.”

Born in a southwestern section of Queens a year before the Great Depression, his father deserted the family, Breslin and his sister were raised by a mother who drank heavily, and Breslin dropped out of high school to head to New York newsrooms, where he quickly became a star. He was seen as a working class hero in the way he spoke truth to power and always tried to support the underclass.

“Early on, Mr. Breslin developed the persona of the hard-drinking, dark-humored Everyman from Queens, so consumed by life’s injustices and his six children that he barely had time to comb his wild black mane,” wrote the New York Times, while noting Breslin’s incongruities. “While this persona shared a beer with the truth, Mr. Breslin also admired Dostoyevsky.”

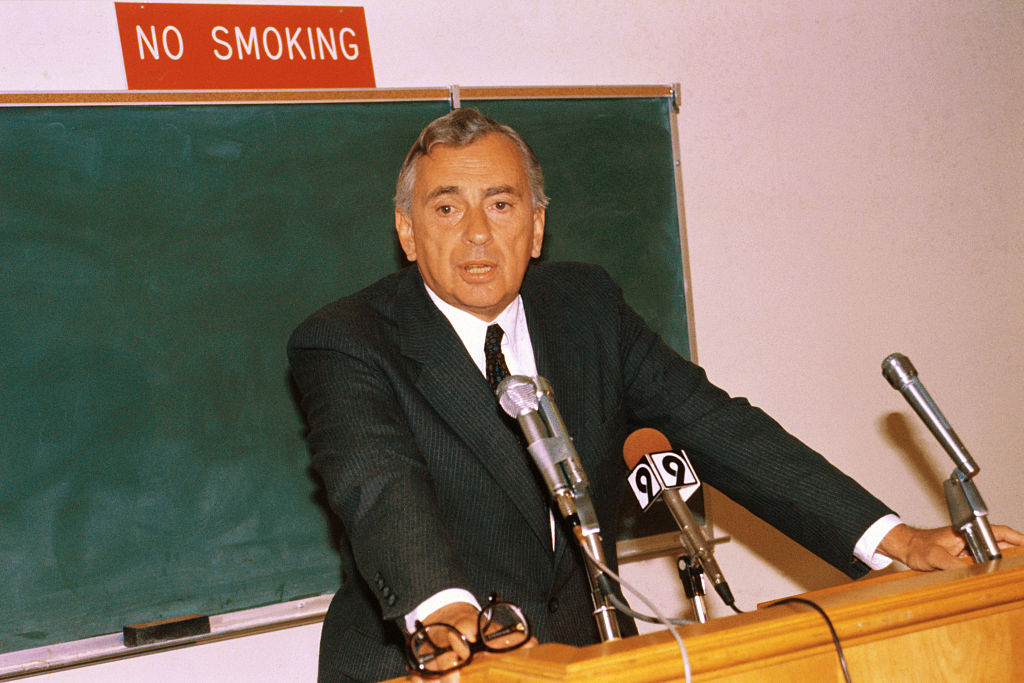

His fame had only skyrocketed since his 1964 Piels work, however. His New York Herald-Tribune column had become syndicated, expanding his notoriety nationwide. He had joined fellow novelist/journalist Norman Mailer in a somewhat jokey bid to win New York’s 1969 mayoral election — they wanted the city to become the 51st state — even using Lion’s Head as their campaign headquarters. He’d also written The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a comedic mafia novel which was adapted into a feature film in 1971.

In 1976 Breslin started working at The New York Daily News, and by the next spring the still-uncaught “Son of Sam” had sent him a handwritten letter — it led to 1.1 million copies of the tabloid selling the day Breslin’s follow-up article ran. Breslin was loving his growing fame too, becoming by then, as the New York Times noted, “a megalomaniacal stylist” who sometimes identified himself simply as “J. B. Number One.” By now, maybe it didn’t seem so weird to have a newspaperman helming your commercial.

The 1978 spot would be a little more cinematic, as it was produced by the legendary Ogilvy & Mather agency. It would still very much have a gritty charm, however, with the location being Farrell’s, a bar opened immediately after Prohibition in the Windsor Terrace neighborhood of Brooklyn. Breslin had been there many times but wasn’t exactly a regular, though his good friend and fellow “deadline artist” Pete Hamill was, having grown up down the block.

“If he was working on a story, Jimmy might go to the bar and start a conversation and see where that led,” explains Jay Casuto, director of an upcoming documentary on the bar, Why Farrell’s? Though, Breslin was frequently snubbed in his queries. Then, as it is now, Farrell’s is a cop bar whose patrons didn’t exactly jibe with Breslin’s progressive politics. Nor did they drink stubbies of Piels back then either. Farrell’s has also been a whiskey and a draught beer kinda place, and the beer of choice there in the 1970s was Piels’s chief local rival, Schaefer’s.

“Original owner Eddie Farrell was a really loyal guy,” explains Casuto. “Through the years he always dealt with Schaefer. So when Budweiser or so and so would come in and try to get on draft, he was the type of guy who would say no.” Casuto assumes Piels must have made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

It almost seems like Breslin is ad-libbing, but the spot was actually scripted by legendary copywriter Julian Koenig. In his obituary, the New York Times would remark that Koenig “created a new style of copywriting that went on to define advertising’s creative revolution. It was smart, simple and accessible to the public — writing that neither exaggerated nor overpromised.”

Upon being inducted into the Advertising Hall of Fame in 1966, Koenig would joke that Breslin was actually a worse actor than the animated Bert and Harry. Still, The New York Times raved about the ad, or, at least its potential effect on consumers, noting that Breslin was “a gentleman of the press, who utters the unforgettable theme, ‘It’s a good drinkin’ beer.’”

By this point Breslin had become a national icon. He would star in a Grape Nuts commercial, every bit as stiff dramatically, though a little more put together. “I happened to like the cereal and I happened to love the money,” he explained in his book of collected columns The World According to Breslin. “I said yes so loud that [the advertising exec] had to hold the phone away.” He’d host Saturday Night Live and a short-lived late-night show in the 1980s. In 1985 he finally won a Pulitzer Prize for “columns which consistently champion ordinary citizens.”

Was Breslin the only future Pulitzer Prize winner to ever star in a beer commercial?

It’s certainly hard to think of any other newspaper columnist today who could pull it off. Mitch Albom? Thomas Friedman? David Brooks?

By the 1980s, beer commercials had become overrun by beefcakes and bikini bombshells who mostly cared about beers that were “less filling.” There were no Joe Sixpacks in commercials anymore and certainly not a beer belly in sight, leading journalist Stephen Binhak to plead in 1985, “Bring back Jimmy Breslin to advertise Piels in a hole-in-the-wall bar, and stop showing me 26 paragons of virility doing it for the Bud Light.”

And that’s not even discussing the ethics of it all. Breslin’s editor at the Herald Tribune, Jim Bellows, had strongly objected to his newsman’s involvement in the commercial, according to Breslin’s longtime literary agent Sterling Lord. (Full disclosure: if you offer me a starring role in a beer commercial, I will throw all my ethics out the window.)

Ultimately, Breslin’s commercial would mark the end of the glory days for Piels. They began to succumb to the marketing pressures of the BudMillerCoors behemoths that were taking over America’s beer scene. In the 1970s, Schaefer bought the Piels label and began brewing this quintessential New York beer in Allentown, Pennsylvania. By the late-1980s, they were bought out by Stroh Brewery out of Detroit. Eventually the label was passed onto Pabst Brewing Company, and by 2015 Piels was no more.

Breslin had slowed down on the drinking anyhow. He claimed that by the early-1980s he was discreetly having bartenders water down his drinks. He would eventually go completely sober, slimming down and focusing on his health until he died in 2017 at age 88.

Even in death, however, his beer pitchman role some 39 years earlier was remembered just as fondly as his Pulitzer, cited in obituaries by the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian and Variety. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo mentioned it in his tribute, too, even if he didn’t exactly get the details right: “He did a commercial for Piels Beer in 1969 or something, where he was in a bar, and he had on a tie and he said, ‘Beer is beer’ or something like that.”

More astute was Jim Rutenberg, who wrote upon Breslin’s death, perhaps explaining why a ruffled newspaperman was, however improbably, the greatest beer pitchman of all time, far superior to a Spuds or a Billy Dee or some Wassup guy:

“He [was] somebody whose word was as honest as it was direct — when he told you in a commercial that Piels was ‘a good drinkin’ beer,’ you believed it.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.