Although nobody needs even more TV recommendations, one of the true bright spots this year has been watching Sacha Baron Cohen’s transition from Borat to Israeli intelligence agent Eli Cohen. The Spy is based on a book about Eli Cohen’s work for the Mossad in the 1960s, when he helped infiltrate the Syrian Ministry of Defense before eventually being executed. Fast-paced and gritty, the series paints a fresh and engrossing portrait of the Israeli operative, even though his fate is made clear from the start.

The reason the show really works, though, is because it isn’t straight history; Eli Cohen’s own daughter has pointed out the factual inaccuracies littered throughout the six episodes. Of course, this is how spy stories have always worked. The subject matter itself involves a world of lies and deceit; it’s no surprise that the writers depicting it tend to stretch the truth and at times outright make things up.

Nobody believes there was somebody working for the MI6 that lived the way James Bond did. Sure, there was probably some suave secret agent somewhere who liked his martinis shaken, not stirred, but Bond is an object of pure fantasy. And that’s fine. From Alfred Hitchcock’s take on the genre to Jason Bourne, the spy story works because of fiction, not fact. The minutiae of gathering intelligence really doesn’t make for a compelling story; blowing stuff up and saving the world while wearing a tuxedo, now that’s a cool story.

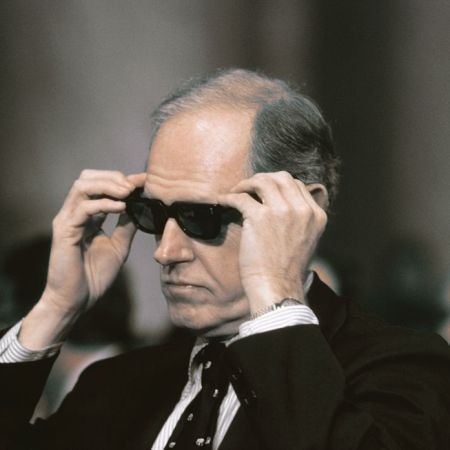

But John le Carré has never dealt in that sort of spy story. That’s probably why he’s had so much sustained success since the early-1960s. The man born David Cornwell is a living expert on the art of real espionage, having served for both the Security Service (MI5) and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) before he found fame writing novels. And at the spry age of 88, he just delivered his latest: Agent Running in the Field.

While le Carré made his name as a writer just as the world was really starting to embrace the spy as a heroic figure, his characters have always been anything but. Instead, le Carré’s talent lies in profiling broken people, using the Kafkan trick of showing how a system can break good people while never venturing into the Kafkaesque. That is, there’s hardly a hint of fabulism or fantasy in his books, and there’s not much sexiness, either. John le Carré deals in a brand an espionage vérité, humanizing people who collect secrets in the name of their government or, in some cases, their own interests.

Yet his latest book comes at a somewhat precarious time in Western history. Almost on a daily basis there’s some new article looking at Donald Trump’s ongoing issues with the intelligence community. At the very heart of the ongoing impeachment inquiry is an unnamed CIA officer.

It could be said that fictional spies, as well as real-life ones, are in an odd position in 2019. They’re tasked with protecting their country, but are caught in the middle of an ongoing culture war. Are they good guys or not? That vague question helps make so many of le Carré books interesting, but he is more concerned with if they’re good people, and how they react to the crushing world in which they operate.

That’s what makes Agent Running in the Field such an engaging read, and one that I don’t think fans of Trump or supporters of Brexit will necessarily like. Le Carré, who has been critical of the American president as well as his own country’s plan to withdraw from the European Union, has found a way to channel his own frustrations into his latest book. The result is a new avenue for the spy novel: a means for exploring political consciousness. It’s not something totally new to his work, but whereas his other books may look at the psychological toll the intelligence world has on individuals, Agent Running in the Field is a distinctly political novel.

But the politics Le Carré focuses on aren’t necessarily about spies working to stop some secret terrorist cell from striking, or any other classic East vs. West plot. Instead, it’s a middle finger to the things the 88-year-old personally finds wrong with the world, told via the actions of a group of misfit and/or over-the-hill agents. And the enemies they are trained on, more or less, are Trump and Brexit. The characters serve as a filter for the author’s not-at-all-veiled beliefs.

And he unloads — a lot. Mostly through Nat, the main character, and one of his colleagues, Ed. One of their first meetings turns into a discussion about Trump: “Britain’s departure from the European Union in the time of Donald Trump, and Britain’s consequent unqualified dependence on the United States in an era when the US is heading straight down the road to institutional racism and neo-fascism,” Ed tells Nat, “is an unmitigated clusterfuck.”

And that’s really just the beginning. While there is plenty of action in the book — though, to be fair, hardly enough for people that crave the sort of action you might get in a Bond or Bourne film — what Agent Running in the Field gives us, instead, is something real. It shows that people have their allegiances and their biases even if they’re tasked with working for a government they might not totally support. I’d say it’s nuanced in that sense, but the way Le Carré frames it sometimes makes Ed’s rants about Trump and Brexit sound more like little manifestos hidden inside a spy novel.

And maybe that is the future of the genre as a whole. Sure, there will always be room for the mass-market paperbacks from the Tom Clancy School of Mega Bestsellers, but as le Carré has shown (and continues to, even as he approaches his nineties), there’s so much more that the spy novel can accomplish, especially as institutions continue on whatever wayward trajectory they’re currently abiding. Embellishment and fantasy might be more fun, but something true — or at least as close to the truth as one can get when writing about people who trade on secrets and lies for a living — is a better direction forward for the genre, and a nobler cause for the authors who traffic in it. That’s always been le Carré’s thing, but maybe now more than ever it feels downright necessary.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.