In the late 1990s, after a stint abroad freelancing as a foreign correspondent, Ken Layne was back in California going on late night drives between Los Angeles and San Francisco and the Eastern Sierras as he liked to do in his formative years growing up in San Diego. He turned on the AM radio and twisted the dial until he found what he was looking for: the voice of Art Bell.

For the uninitiated, Art Bell was the founder and original host of Coast to Coast, a wildly popular late night call-in radio show that entertained all things weird, paranormal, and conspiratorial. “[Bell’s show] was just fantastic, weird radio theater,” Layne told me in a phone conversation. “It was very spooky, entertaining, and funny, all at the same time” and made for “good company on the road and late at night.”

Broadcast from the tiny town of Pahrump, Nevada, an hour west of Las Vegas, Bell abandoned the usual scripts of political talk radio in favor of more controversial topics such as gun control, the occult, and, his signature, UFOs. Although Bell did not endorse the conspiracy theories peddled by his callers, he was a master showman and knew these eyewitness accounts furnished with exacting detail made for excellent entertainment. Bell, who died on Friday the 13th in 2018 at the age of 72, remade radio, reaching as many as 10 million listeners weekly during its heyday.

When Layne started his own radio show in 2017, he too wanted to “plunge listeners into a shadow world.” The result was Desert Oracle, a 28-minute show airing every Friday night at 10 p.m. PST in which listeners can expect “evocative tales of lost mines, UFOs, missing tourists, secret military projects, local legends, weird animals and weirder people.”

Talking in a nasally, seen-it-all drawl, Layne’s hard-boiled radio personality grabs listeners by the lapels, pulls them in close and says, “Listen, man.” Produced with lo-fi distortions, the radio show has a post-apocalyptic air to it, as if Layne were sending radio dispatches into the ether from a slow-rolling global collapse. But what he’s actually noting is the very real sunset of American empire.

I imagined Layne broadcasting from a dingy tin shack with a crowd of antennas perched overhead like mangled antlers. In truth, the show is produced from a local radio station sandwiched between a liquor store and an Indian joint and located along a highway where military convoys drum by every now and then. Since the pandemic, however, Layne has produced the show from his home office, which offers a wholesome view of desert life: coyotes, skunks, and a hawk’s nest perched in the upturned armpit of a joshua tree.

Funnily, the so-called “voice of the desert” is not actually a native of the desert. Originally born in New Orleans, a city rich with its own paranormal voodoo history, Layne grew up in Phoenix, Arizona, where his father was sent to convalesce in the dry air of the Sonoran desert. He then spent his formative high school years in straight-laced San Diego and, as soon as he got his driver’s license, he’d go for long drives out into the vast expanse of the desert, frequently visiting Joshua Tree, where he resides today.

Layne’s radio show was not his first project under the moniker “Desert Oracle” nor his first venture in radio. Layne did college radio and then again while living in Central Europe, but he quickly tired of the restrictive formats. “I didn’t want to DJ, I didn’t want to have a politics talk show, and I hate NPR,” he told me. The nimble freeform of podcasts, coupled with Coast to Coast as malevolent mood board, afforded Layne the flexibility he needed to land on a format he found agreeable. The weekly radio show is now 111 episodes deep, the latest of which digs in to the mysterious Utah monolith, which went viral after being discovered by a wildlife crew flying low to count big horn sheep.

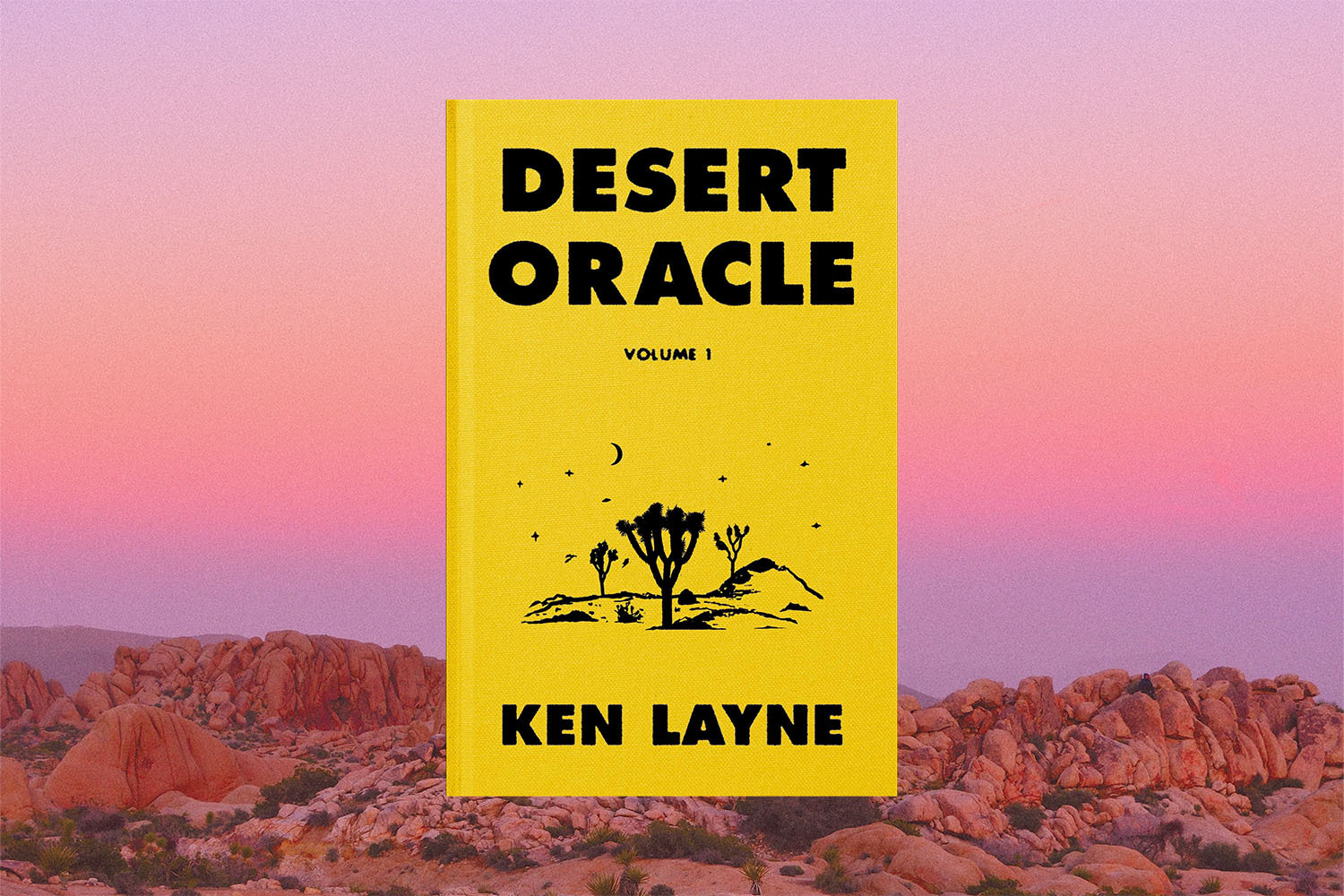

Before it populated the air waves, Desert Oracle began as a quarterly publication Ken produced solo. Styled after mid-century field guides, the loud yellow cover at once beckons and warns readers, as if trespassing into fenced-off fields of knowledge. Published on a loose quarterly schedule, a typical pamphlet runs about 44 pages and contains a variety of stories, old and new. Adorned with black-and-white illustrations, these stories range from local lore about the Yucca Man (the desert’s Big Foot), UFO sightings, nuggets of biographical information about cult-figure Edward Abbey, and helpful how-to’s on surviving in the desert.

A regional publication, Desert Oracle may seem to target mystics and desert rats, cryptozoologists and RV homesteaders, but it’s actually for anyone who has ever been moved by the desert — that strange landscape stripped down to the harshest of elements: sun, rock and sand.

It’s widespread popularity is evidenced by the fact that MCD, a division of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, recently published a collection of these quarterlies bound into a single hard copy. True to the original, this collection is bound in a yellow jacket, furnished with black-and-white illustrations, and bursting with the bizarre. Flip to any page and you’ll find something that could belong in Ripley’s Believe It or Not.

In addition to desert weirdness, Layne infuses Desert Oracle with a conservationist spirit. Not shy about politics, Layne frequently rails against corrupt goons in government, environmental negligence, and widespread nihilism toward climate change. The threats to the desert are not necessarily unique, but they are chronic and plentiful: severe drought, encroaching development, escalating wildfires, invasive species, AirBnbs and so on. During our conversation, Layne audibly softened talking about bobcats who were aggressively hunted for their furs, which fetched as much $1000 per pelt on the global black market, until bobcat trapping was banned in 2015.

The fact that the desert is somewhat pristine relative to other regions today was a complete “accident,” according to Layne. He explained that when Major John Wesley Powell surveyed the Colorado River in 1869, he concluded the desert was a “wasteland” where nothing could grow and, because of this, large swaths of desert were placed under the control of the Bureau of Land Management which still oversees much of it today.

The biggest wasteland of all — Death Valley — was where the desert first enchanted Layne and also how he discovered the great bard of the desert: Edward Abbey. “I had convinced a couple of my delinquent friends to go to Death Valley with me over Christmas break in my last year of high school,” Layne tells InsideHook. “It was the Mojave like I love it most: freezing, snow on the mountains, high winds. It was like we dropped out of a military cargo plane into some unpleasant wilderness.”

Upon returning to his “dull teenage life of convenience,” a restless Layne scoured the library for anything desert-related and walked away with a copy of Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey. Abbey was a disgruntled seasonal park employee working alone in Arches National Park in southwest Utah, an area he cherished for its harsh beauty and mystic solitude. Ironically, Abbey’s impassioned writing about Arches drew legions of tourists, mystics, and desert rats chasing the same elevated communion with nature and solitude experienced by Abbey. With it, they brought all the infrastructure of tourism — cars and pavement above all — which harmed the very environment Abbey held so dear.

Layne saw Abbey as a kindred spirit and proof that someone could live the kind of life he wanted. “Maybe it was unlikely,” he says, “but at least there was evidence of someone attempting it.”

As the Desert Oracle, Layne embodies the best of both Art Bell and Edward Abbey. A more accurate moniker for the so-called “voice of the desert” would be, in my mind, the ranger of the desert. “Being a ranger shouldn’t even be a job,” Layne says in Episode 31, “A Ranger’s Life.” “It’s a vocation, a calling, a mission — something more like being a Buddhist monk than a policeman.” But, like Abbey, Layne is a ranger gone rogue. He answers to no one but the desert.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.