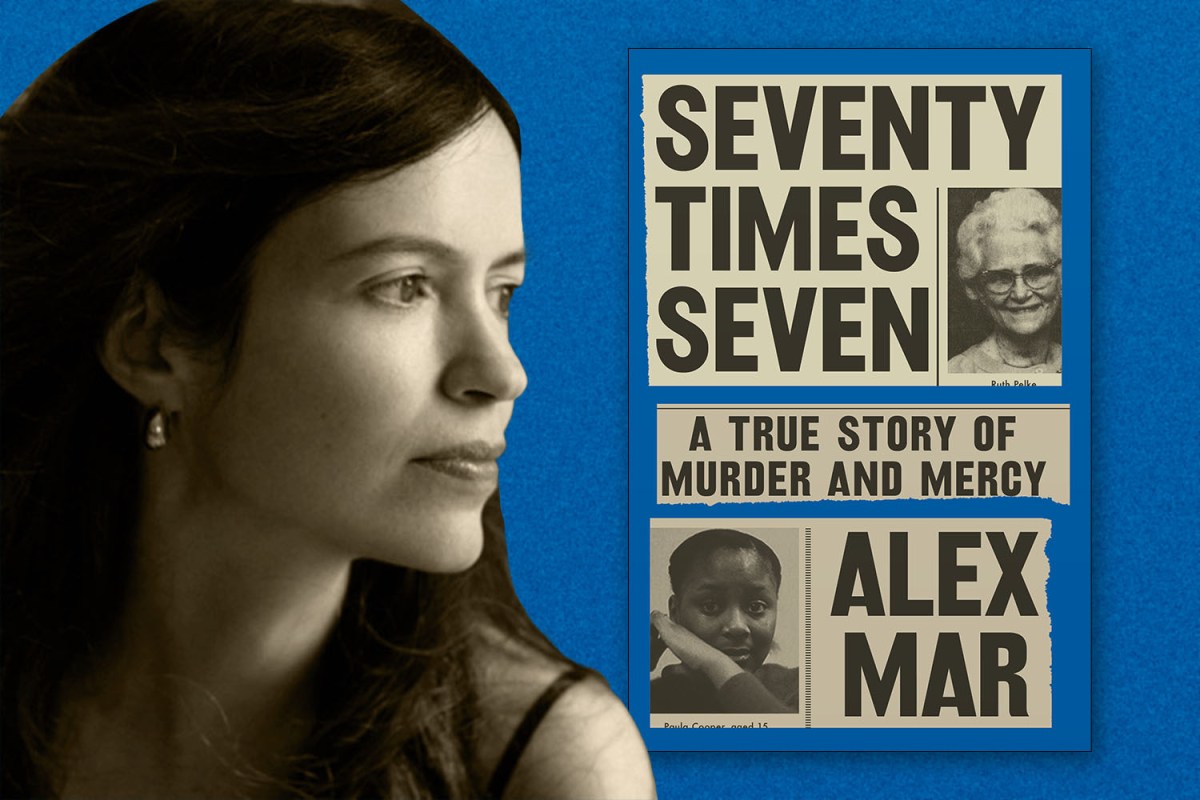

It wouldn’t be entirely correct to call Alex Mar’s new book a work of true crime. Yes, there is a crime at the center of Seventy Times Seven: A True Story of Murder and Mercy. And yes, this is a highly researched work of nonfiction. But it’s about things that go beyond what you might expect; in telling the story of Paula Cooper, a high school student sentenced to death for her role in the murder of Ruth Pelke, Mar touches on everything from Constitutional law to the political power of the Vatican.

Seventy Times Seven is also a book concerned with questions of ethics and belief, and how their combination finds unlikely allies on similar issues. The end result is a moving and thought-provoking work of nonfiction which was recently hailed in the pages of The New York Times. We spoke with Mar about the genesis of this book and its relationship to her previous book, Witches of America. An edited version of our conversation follows.

InsideHook: How did you get from writing a book about witchcraft to writing a book about capital punishment and the movement against it?

Alex Mar: I see this book as one that addresses the death penalty and wrestles with that and what capital punishment says about us as a country. But for me, it wasn’t a book about capital punishment. I think the through line in my work, whether it was my first book or my long-form stories, has to do with the belief systems that drive us. That was the case with my documentary as well, American Mystic.

With Witches of America, that was very obvious. That was the theme that was in the books, I believe. But in this case, I really saw this as a story where a community was profoundly shocked and discouraged by this one act of violence. How do you respond to that? Everyone involved falls back on the various belief systems that guide them as individuals. In a lot of cases, that’s faith, or they’re turning to the law, or they see that the law actually contradicts with their personal faith and what then.

But also, there’s this question for me. One of the through lines of the book is that if you say you’re a devout Christian, let’s say, that ends up playing out in this country in so many different ways where questions of justice are concerned.

In this case, you have the victim’s stepson, who’s a devout Baptist, who is ready for this girl, who’s 15, to be put to death. His son, Bill Pelkey, takes a totally different tack, even though he also thinks of himself as a devout man. And the appellate attorney who ends up fighting, perhaps the most passionately on policy to have, is actually an atheist. She has no idea what drives her to defend people in that position, right? So for me, that was the connection.

How did you find your way into the story? Was it through the activists? Was it through researching the case?

When it was more in the news, my instinctive interest at the time was in learning more about violent crime committed specifically by women, because the percentage is radically smaller than that of the number of violent crimes committed by men. And so I was exploring that, trying to understand what patterns that I might see in cases that I could find or in literature around that. I mean, I must have looked at more than 1,000 case summaries.

And along the way, I found out about Paula Cooper’s case and I was immediately struck in a much more personal level by the fact of her age, the fact that she was only 15, and then also the fact that the victim’s grandson chose to forgive this girl who had brutally killed his grandmother. At the time I’d never heard of something like that. In the years since, I’ve met several people who have made the same choice.

Those were the two elements that really sunk their teeth in me. And I found that everything else dropped away and I really wanted to focus entirely on this particular story.

Very early in your book, you point out that there’s no ambiguity about the murder — both the act itself and who committed it. What were some of the challenges of writing about something like that and trying to recount the nuances and the history and everything else?

To my mind, there was something really challenging about writing about a murder case that was not an instance of wrongful conviction, and there was no chance of that. A lot of coverage, whether it’s books or podcasts or TV series that deal with retelling true crime stories — I don’t really think of this as a true crime book, but that’s another topic. But I think in most of those cases, you’re left with the possibility of, do we really know if this person committed the crime? Have they been unjustly imprisoned? All of that.

I’m going to try to simplify this. I think that one of the big challenges here is that the reader is confronted by this truly brutal act that took place in the absence of any kind of logical motive. And then you have to grapple with whether or not you have room for empathy for this girl. That was a huge challenge for me as a writer because if you can’t get the reader to keep their mind open, then you’re building a book around a key character who is seen as completely unsympathetic.

I personally never want to take on a major project in which I can’t imagine my way into that person’s psyche on some level, have some kind of empathy for them, see them as multidimensional. So it was really important to me to get some understanding of Paula’s childhood and the circumstances around that moment of the crime and to have the reader be aware of that before the crime is described.

I think the timing of where these events are placed in a book really changed the stakes. I mean, it’s a really significant choice. So I think if it’s more of a genre book, I think it’s more typical to have the crime kind of up front and then backpedal. But I wanted people to sort of live with this kid, the close relationship with her sister and these recognizable childhood scenes in their home — but also a lot of the struggles of her moving around between emergency shelters and foster care and juvenile detention and constantly being sent back over and over to her dysfunctional and abusive family home. It makes it much more possible to imagine the circumstances of the crime — the idea that this girl may have snapped that day, you know?

One of the details that stayed with me was of these kids joyriding in the car owned by the woman they’d murdered. I feel like that gives a good sense of them as kids who don’t grasp the consequences of what they’ve done.

Something I discovered that went completely unmentioned in the coverage of the crime at the time is that the victim was found with her wedding band and her diamond ring still on her finger — and her watch. It was framed as a home invasion and a robbery. There’s no seasoned criminal who’s going to break into a home and leave those things there.

There are just so many chaotic elements to the crime. To think about the fact that not that long before she was listening to Jackson 5 records that she got off the back of a cereal box with her sister and watching the Three Stooges on the TV. The degree of loneliness, abuse, instability in her life at such a young age — to me, that was shocking and also really moving.

One of the other things that really struck me about Paula that I do want to mention is she bounced around between about 10 different schools by the time she was arrested and predominantly skipped class. Once she was in prison and on death row in such extreme isolation, through her letters to so many people who were curious about her and her case — and I read hundreds of these letters — she really revealed herself to be this very intelligent, very unique kind of personality. And it just makes you wonder what she would have been able to accomplish had that one afternoon in May gone differently.

Earlier, you spoke about not considering this to be a true crime book. At what point in the writing of this did you decide that it wasn’t going to follow that kind of pattern? Do you see this book as having elements of a media critique in it?

With the true crime thing, I want to be specific. I think when I see this book as a sort of hybrid, it has this aspect of being literary, deeply reported true crime in that it is about true events. But also, it’s a slice of recent American history. I do think it has a legal thriller element to it as well.

I think that what takes it out of the immediate easy categorization of true crime is that it looks at the evolution of these different pieces of the system over time. The crime really is the catalyst at the beginning of the book for all of these relationships. It’s not a whodunit. So for me, at the heart of the book was also this question of what roles does forgiveness or mercy play in our justice system?

In terms of the media critique aspect of it, I was really aware throughout researching and writing the book that there’s a lot of storytelling involved with crime and punishment in our culture. The victim’s family is encouraged by the prosecutor to support a certain story of how the event occurred. The defendant has another story. The press has their own story that caters to a narrative that is already floating around in the neighborhood.

And so when you then appeal on Paula’s behalf, for instance, the attorneys have to help to shift that narrative. In this case, they bring in the support of the international press, of the Vatican. For me I was really thinking about the stories that, in a cumulative way, end up determining what justice is in any scenario. What the community will accept as a just outcome. I don’t know if that’s too abstract of an answer for you.

Not at all.

I will say that a huge influence on me was definitely Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song. That was probably the single greatest influence on this book — and he has this really smart depiction of how the media functioned in the coverage of the Gary Gilmore case. He called them “the Eastern voices descending in the West.” And so in some ways, that was in the back of my mind.

One of the shocking facts that came up in the book was learning that 10-year-olds were eligible for the death penalty for a time in Indiana. Were there any other facts that you turned up in your research that were especially unsettling?

That was absolutely a huge shock for me as well. Paula Cooper’s death sentence forced people in Indiana to confront that at the time, they had no idea what was on their law books. The average person in in Indiana had no idea that you could technically sentence a 10-year-old to death in their state. No one had an understanding of that. And so you had someone like Representative Ermine Rogers, who was a longtime Gary native and a public school teacher who had run for public office, who single-handedly decided to lead this crusade to raise the minimum age. A huge part of her argument was just, you know, did you even know that this was on the books?

Overall, I think when I started to connect Paula Cooper to the larger stories of the death penalty for teenagers in this country, I learned a lot that I had been completely ignorant of. This country has executed at least 366 juvenile offenders, and more than 200 of those were sentenced to death. Everyone who’s received a death sentence for crimes committed as a teenager, more than 200 of them were handed those sentences after 1973. So this isn’t all like, “Oh, this happened in the 1800s,” right?

I was thinking about how this came to an end as a practice so recently, in 2005. So it’s just such a challenge to us as a country and as a culture. What does that say to us that that was considered constitutional until so recently? And it leads immediately into, well, we also happen to be the only country in the world that still sentences children to die in prison. We sentence kids to die in prison.

We have life without parole. We’re unique in having that sentence on the books today. We’re really this bundle of very uncomfortable contradictions in that we claim as a culture to offer special protections and special status to children, right? Often in very politicized forums, people love to bring that up, but the reality is a lot more complex and quite a bit darker.

Maya Moore Takes a Break From Basketball to Help Reform the Justice System

Moore is taking a sabbatical from the Minnesota Lynx this yearSome of the things you write about here were also entering the larger discourse at what I assume was the time you were writing it — like the argument about whether humans’ brains are fully developed before age 25. What was it like to be writing a book like this where so many of the themes that you were reckoning with were being debated and at some points even changing over the time that you were writing it?

Writing the final chapter became increasingly difficult because I found myself forced to rewrite it over and over. The Trumpification of the Supreme Court was really starting to become a reality while I was still finishing the book. And we were all watching in real time, little by little, the evidence of there that was going. I recall some of the attorneys I spent years chatting with, the fact that the conversation would inevitably veer into, “Oh my god, what are we going to do?”

There are a lot of attorneys who I got to know through this book who no longer want to get important issues in front of this Supreme Court. There’s a certain movement to see if the death penalty’s minimum age should actually be raised higher to be consistent with what neuroscience is telling us about brain development. But no one wants to get it before the court because the conservatives on the court have proven that they don’t necessarily have respect for precedent as they’re supposed to.

The legal progress that was made around the death penalty for kids that the book describes would not have been possible if you couldn’t consistently strategize around the moves of the court, how they would respond to certain kinds of legal arguments, certain kinds of evidence for the consensus. If the court isn’t playing by the rules, or certain justices aren’t playing by the rules, then there’s really no way to game it, to put it crudely. So it’s such an uncertain moment with the Supreme Court right now. That’s not news.

But it’s frustrating to watch. They backpedaled on some of the progress made around how teenagers are treated by the system. And so you see how urgent it is to really have voices advocating behalf of offenders of this age group, right?

In your previous book, you were more of a presence in it. Was that ever something you considered with this one or did you kind of know that you were going to be stepping back and not being a presence in this narrative?

That’s really something I think about a lot where nonfiction is concerned. When is it a really powerful tool to insert the first person? I was really open to doing that when I began the process of writing this book. Very quickly, I shut that down because I felt in a deep way that it would have been an act of hubris. The material is so intense that framing it with my own first-person experiences just seems trite in comparison.

I found myself, as I was looking for the voice of this particular book, stripping away. I kept subtracting that from the prose. I think it’s one of those cases where, I guess in general, each project tells you what its voice is supposed to be. That’s where this landed. I’m really excited to inject more of myself into the next one so I can kind of be a little more grounded in my own life and perspective next time around.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.