You usually don’t have to wait long for a new book on Ernest Hemingway to come out. Biographies on the Nobel Prize-winning writer make up their own little cottage industry at this point, arriving on bookstore shelves throughout the year. Sometimes the books look at Hemingway the writer, other times Hemingway the traveler and often Hemingway the drinker. The problem with so many books on the man is that, more often than not, these books don’t really give you anything new.

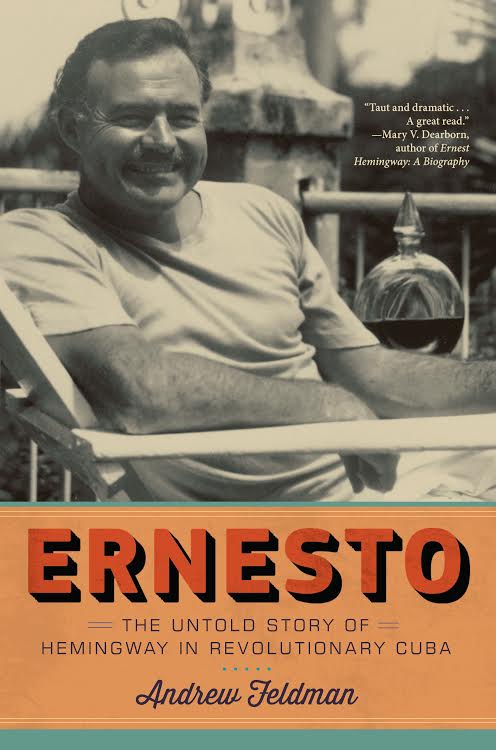

Ernesto: The Untold Story of Hemingway in Revolutionary Cuba, the new biography by Andrew Feldman, who spent two years as the first U.S. researcher allowed to study at Hemingway’s residence at Finca Vigía, takes the old Hemingway stories, and gives them new life. Using place as a way to tell the legendary writer’s story.

While the writer’s experiences in Cuba do make up a big chunk of Ernesto, one section of the book in particular, where we see Hemingway in Paris towards the end of the Second World War, drinking brandy out of a fish bowl with the photographer Robert Capa and reclaiming a famous Parisian bar caught our eye.

We’re happy to share that section of Ernesto: The Untold Story of Hemingway in Revolutionary Cuba, by Andrew Feldman.

Like Martha Gellhorn, Mary Welsh Monks was a lady as well as a war correspondent who wore her femininity and good looks conspicuously in the male-dominated profession. The daughter of a lumberjack from Minnesota, Mary was based in London, reporting regularly for the Daily Mail and writing features for Time magazine. One day in the press cafeteria, she appeared in a skintight sweater that accentuated her breasts and aroused the boys. It had gotten so hot in there, she explained in her tell-all memoir, How It Was, that she had been obliged to remove the jacket of her press uniform. Ever since her mother had tried to “harness” her into one at the age of twelve or thirteen, she had not owned a bra. “God Bless the machine that knit that sweater,” announced friend Irvin Shaw when he saw Mary’s nipples protruding, and he predicted that she would soon attract a swarm of admirers. Sure enough, as the fellows trickled into lunch, they complimented, “Nice sweater!” “The warmth does bring things out, doesn’t it?” and so on, as they passed their table. Amidst this herd of horny stags appeared bright-eyed Ernest Hemingway, nudging Shaw to introduce him to his lady friend.

“Above the great, bushy, brindled beard, his eyes were beautiful,” Mary thought, “lively and perceiving and friendly.” His voice struck her as “younger and more eager than he looked,” yet she sensed an “air of solitude about him, loneliness perhaps.” The pair made a date for lunch. Later inviting himself into the room Welsh shared with Connie Ernst, Ernest subsequently disenchanted Mary when he demonstrated to them that he was not nearly as interesting to converse with as he was to read or read about. Though Welsh hinted that he take leave by indicating that she had to get up early the next day, Ernest sprawled across their twin beds and whined about his overbearing mother who had never forgiven him for not getting killed during World War I, had never cooked, had bought fifty-dollar hats at Marshall Field’s, and had forced him to accompany his prudish sister, Marcelline, when she could not had get a date to the prom on her own.

Although she was still married to her second husband, Noel Monks, an Australian reporter, inspiredly following conflicts to Ethiopia, Spain, France, England, Italy, Egypt, Papua New Guinea, Korea, and Malaysia, their marriage was perhaps already on the rocks as she seemed to be dating several other men. During their third encounter, Ernest shocked her with the declaration of his intention to marry her, and Welsh was repelled initially by his personality and his pre- mature declarations of matrimony. Mary’s roommate wondered how she could be so “tough on him” and encouraged Mary to give him a chance: he seemed so lonely, she said, and after all, a gal did not get a chance to marry a guy like that every day. “He’s too big,” replied Mary, “thinking both stature and status.”

•••••

When the photographer Robert Capa heard that his buddy from the Spanish Civil War was in London, he decided to celebrate with a party at his flat in Belgrave Square: “I bought a fish bowl, a case of champagne, some brandy, and a half-dozen fresh peaches. I soaked the peaches in the brandy, poured the champagne over them, and everything was ready. At four in the morning, we reached the peaches. The bottles were empty, the fish bowl dry.” Returning from Capa’s party, Ernest’s automobile hit a water tank. When the call came just before dawn, Capa and his girlfriend rushed to the hospital.

“After forty-eight little stitches, Papa’s head looked better than new,” Capa remembered fondly, years later. When Papa turned his back to the merry couple to submit to a weigh-in from an attendant nurse, Capa’s girlfriend, Pinkie, lifted his surgical gown while Capa snapped a photograph and snickered at the writer’s glorious buttocks. Receiving visits from his gang, he disobeyed doctor’s orders, drinking in the hospital and hiding bottles beneath his bed. Papa would be required, all kidding aside, to stay in the Saint George’s hospital for several days and would complain of severe headaches for months after. Sensationalizing the event, the news mistakenly reported him dead.

When at last Martha arrived distressed but alive in London, she checked into the Dorchester Hotel where her husband was staying. Hearing that he had been in an accident, she tracked him to his hospital room where she found him with his stitched head wrapped in a turban and emptied bottles of whiskey and champagne beneath his bed. Infuriated by his enjoyment and indifference to her ordeal, Martha informed him that they were “through, absolutely finished” and walked out. Walking out on Ernest Hemingway was the one thing that a woman, particularly a wife, should not do. Spurred by his feud with Martha, Ernest neglected his health and put himself in harm’s way, following the war with frenzied energy while pursuing his romance with Mary Welsh from June to December of 1944.

To cover the invasion of Normandy, Ernest boarded a transport ship, Dorothea L. Dix, on June 6, then a landing craft, Empire Anvil, but awash amidst the waves while artillery blasts shook the smoldering earth, he was not permitted to go ashore, allegedly, so he returned instead to Mary Welsh’s bed in the Dorchester Hotel, causing Martha to fume as she left for the front: “I’m leaving for Italy . . . I came to see the war, not live at the Dorchester.” In contrast with her soon-to-be ex-husband, Martha came ashore with the troops to cover the Allied invasion of occupied France as well as report on the liberation of concentration camps like Dachau and Auschwitz. Not to be outdone, Ernest exploited his celebrity status at the end of June to procure invitations from Royal Air Force crews flying missions over the English Channel to repel German V-1s, the “buzz bombs” that had been attacking Portsmouth and London since the middle of the month; he also appeared in boxing gear, shirtless, and with a full beard, shadow boxing in a feature for Look magazine.

Meanwhile, the Polish Resistance was putting up an inspiring fight against Hitler’s forces and calling for Soviet and American intervention. While Allied forces air-dropped supplies during house-to-house fighting, the Soviet army (only twenty miles away from the battle) abandoned the Poles in their hour of need. It was to become one of the great ignominies of the war. During the uprising, Hitler ordered the complete destruction of Warsaw: thus 80–90 percent of its buildings, artworks, and books were destroyed or stolen by German troops. By the beginning of September, the last of the resistance fighters were killed or captured and sent to concentration camps.

During the liberation of France, Ernest took command of a ragtag band of ten resistance fighters from the village of Rambouillet (just outside of Paris). Present on August 19 during the liberation of Paris, he had “liberated” a German motorcycle and sidecar for his personal use (and reopened his still-healing skull by crashing it into an anti- tank gun) and also “liberated” the Ritz Hotel—and bar—where he requisitioned a large room and proceeded to faire la fête, allegedly ordering sixty dry Martinis for his rowdy company of adventurers. One reviewer, David Hendricks, put it well: “During the war, Hemingway was good at being Hemingway.”

For violating the Geneva Convention’s rules for noncombatant journalists, Ernest would have to face a military tribunal in October. Lying under oath, he “beat the rap” to protect himself and Colonel David Bruce by swearing to Colonel Park, who convened the hearing, that he only acted in an advisory capacity. In August, Ernest arranged a transfer from General Patton’s Third Army to the First and attached to the Fourth Infantry Division’s Twenty-Second Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Charles “Buck” Lanham, who became a lifetime friend. In September the Germans began to launch their long-range missile, the V-2, at targets in London, continuing bombardments there, in Liège, and in Antwerp until March 27, 1945.

From ERNESTO: The Untold Story of Hemingway in Revolutionary Cuba by Andrew Feldman. Used with the permission of Melville House Publishing. Copyright (c) 2019 by Andrew Feldman.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)