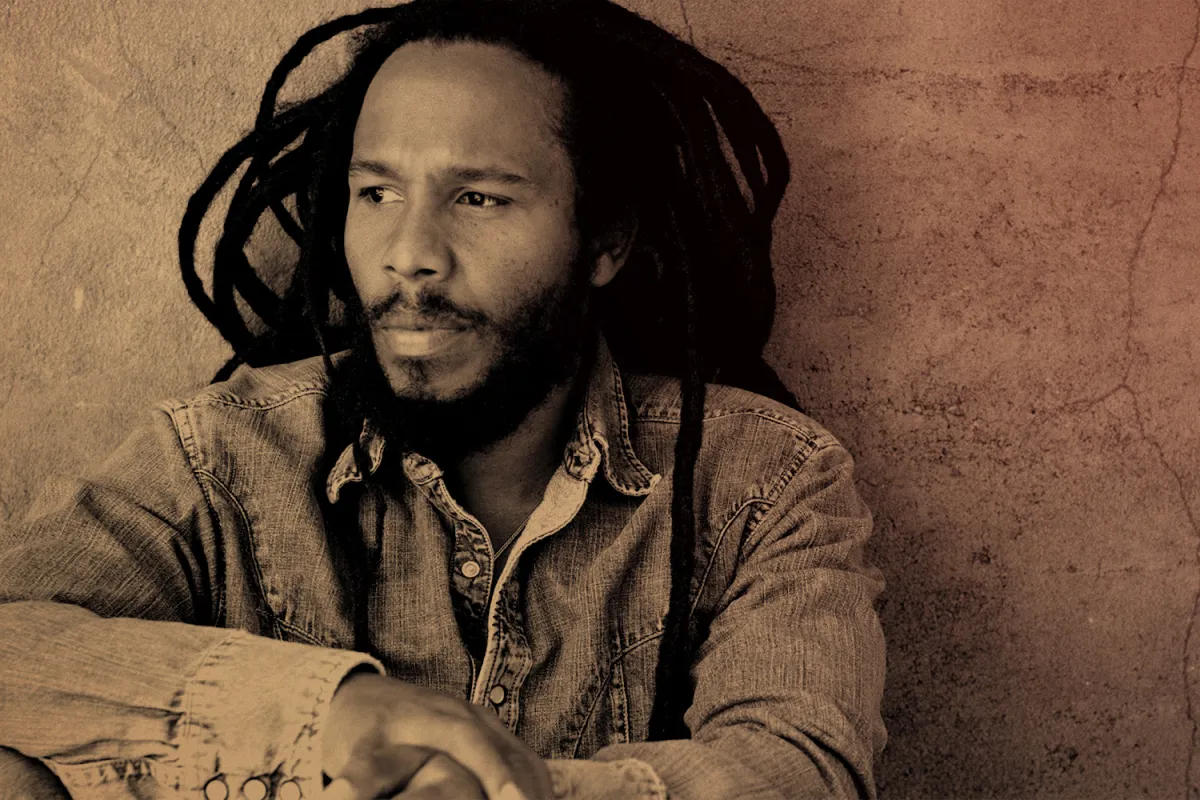

There will never be a day that Ziggy Marley isn’t synonymous with his father, Jamaican reggae legend Bob Marley. The eldest child of Bob Marley and his wife Rita (of 11), Ziggy has helped carry on his father’s legacy through his music, activism and philanthropic pursuits since his death in 1981.

Marley, also an eight-time Grammy Award-winning artist who’s made waves with his own band, Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers, turned 53 last month (October 17), and beyond his musical pursuits, he now dabbles in book publishing. Earlier this year, commemorating what would have been his father’s 75th birthday, he edited a photo book of behind-the-scenes photos called Bob Marley: Portrait of the Legend compiled from shots taken between 1976 and 1980.

He also recently released a children’s book called My Dog Romeo, which details the story of a boy and his dog, somewhat inspired by Marley’s own acquisition of a Lagotto Romagnolo during the pandemic.

Last week, he published a second children’s book, Little John Crowe, that tells the story of vultures that live in Jamaica, and how they’re integral to the ecosystem. Both books were released by Akashic Books.

While waiting on hold for Marley — who has seven children of his own — reggae predictably filtered through my headset. This was the hotline of Marley royalty, after all. Once he picked up the phone a minute later, we proceeded to chat to about the art of storytelling, collaborating with Israeli and Palestinian youth and the song he wrote for George Floyd.

InsideHook: Where did the idea of Little John Crowe come from?

Ziggy Marley: It is based on me growing up around vultures in Jamaica. I finished writing it during the pandemic but started writing it many years ago. It’s based on my experience and bringing the plight of vultures to an audience for them to understand their importance, and the importance of nature in the ecosystem we live in.

Is writing a children’s book a way for the younger generation to learn, early on, how to take care of the planet?

Yeah, and there’s different kinds of species of vultures that are being taken out of their habitat. Some vultures are endangered, also. It’s important that we be mindful of this species that is so integral to keeping disease away from human beings.

How is writing children’s books an extension of songwriting?

For me, writing a book is a way to expand my own mind and have more space to tell more stories. Songs usually have a certain structure to them. Writing a book is a much deeper palette, where I can be more imaginative — it’s an adventure. I love doing it.

You have seven kids … Do you use storytelling to pass on wisdom to the younger generation, from things you’ve learned from your own parents?

For me, for my younger kids, I’ve told them stories I used to be told in Jamaica. Storytelling was a big part of my upbringing. I continue to do it with my own kids. But some of the stories aren’t even by books, it’s just by memory. With this book, I’ve read it to my 4-year-old and my 10-year-old. It’s part of our legacy in storytelling in music and now in books. From memory, also, my aunts told us stories.

What books inspired you growing up?

Fantasy books. I read a lot of comic books growing up. Things I can imagine, or things that pique my imagination. I’m drawn to that superhero world, or the Lord of the Rings and Star Wars type of stuff, that’s what makes my imagination take off.

Last year, you released a song called “Lift Our Spirits, Raise Our Voice,” which was inspired by the protests following George Floyd’s murder in 2020. What were your feelings around that?

Everyone has their own way of expressing themselves. I did a march with kids on the street in Los Angeles at that time, but I was not deeply, physically involved in the actions of protests in the streets. My way of expressing solidarity for what was going on was writing songs. And share that song with the world. Maybe it can inspire positive change, consciousness about real situations that affect us. I had an emotional reaction to what I saw at the time, with the George Floyd situation. As a human being. The song came out of that reaction.

The message of music is key to you. Do you use it as a form of expressing peace and unity?

I wouldn’t say I was using it; I would say it’s using me. I would flip that around. I’m inspired to write songs. I’m not a political commentator, an editorial person or a writer. What affects me emotionally is what I write about. I have a visceral feeling about this that just comes to me. I’m not a professional writer. Writing is not my job. It’s spiritual.

What was your experience like working with the Jerusalem Youth Chorus and Palestinian chorus singers?

It wasn’t in-person because it was during the pandemic, so it wasn’t as palatable. But my wife is Israeli, I’ve been to Israel many times. I’ve spoken with Palestinian people and the diaspora in Israel. It was a natural thing to me. It’s youth and it’s about peace and love, bringing people together. To find a solution that is outside of the political realm. Which feels difficult for those people to figure out. But for the younger generation, it’s easier for them to talk about being peaceful and living together. Having peace. This is the best avenue to see a true solution to the problem that the region faces — the youth and through music.

Can you tell me about the charity work you are doing with your foundation, Unlimited Resources Giving Enlightenment (URGE), which helps children in Jamaica and Ethiopia?

Our charity called Urge helps us work with children. We do a lot of work with schools, it’s about the lifestyle we live, giving back as an extension of who we are. It feels normal for us to do that.

What do you say to people who say, when you sing, that you have the same voice as your father? Is it a compliment?

Not exactly, but people love Bob Marley so much, they imagine things sometimes. [Laughs.] A lot of people have never seen him live or knew him personally. So when they see me, they use their imagination. That’s okay. I’m biologically and genetically linked to him, but we all have genetic traits from our parents. It’s not something I take as a negative, I take it as a positive.

When you sing your dad’s songs like “I Shot The Sheriff,” you’ve said that you sing them “in the present about the present, not as about the past.” What does that mean?

I just did a tour. When I sing my father’s songs, I make them my own. I’m not just singing his songs; I’m feeling the emotion of the times we’re living in and how they’re connected to the time we’re living in. and how that comes across when I sing them. I’m not just mouthing the words, I’m feeling the words, with true emotional content, rather than just saying the same words. My emotions and the times we’re living in are put into each song. The songs are still relevant, too. To me, and to the audience, they’re feeling the songs in a way that is beyond a tribute. They’re feeling it because it’s expressive of what we’re going through in life right now. It goes deeper than just mouthing the words to my father’s songs.

You recently put together a photo book to honor your father, Bob Marley: Portrait of a Legend, do you remember what it was like going through his photo archive?

It always brings back memories for me as a child. And how young my father was. I’m so much older than he was when he died, you know? [Marley was 36 when he passed away in 1981.] But I’m still young. He was like a baby, compared. It’s fascinating to me that he put so much into that small number of years he was here. It lasted lifetimes and generations, it’s still melancholy and sad that he was so young when he passed away. When I look back, it’s a mixture of joy and sadness.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=450%2C450)