At a crucial moment in American history, two scientists — Gloria Hollister and William Beebe — explored the depths of the ocean, with Beebe situated in a bathysphere half a mile underwater. Beebe would go on to write a book about his experiences, Half Mile Down, which was published in 1934; Jacques Cousteau would cite him as an influence on his own explorations.

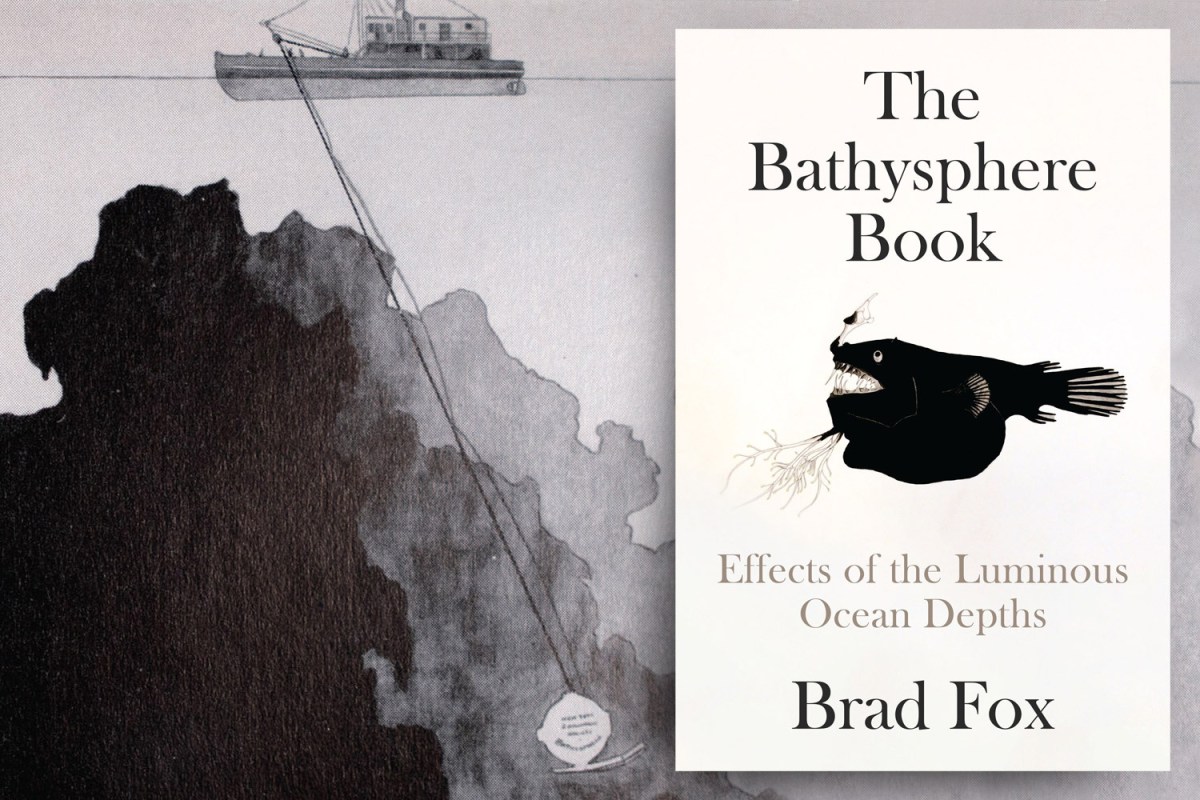

In his new book The Bathysphere Book: Effects of the Luminous Ocean Depths, Brad Fox chronicles the circumstances around that fateful dive, while also recounting the other historical figures whose paths crossed with those of Hollister and Beebe. It’s a fascinating and at times unsettling work of nonfiction, made even more compelling by the numerous sketches and illustrations found throughout.

We spoke with Fox about the process of researching this book, the pandemic’s unanticipated alterations to it and some of his own underwater experiences. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

InsideHook: Was the history covered in The Bathysphere Book the first time you really became interested in the depths of the ocean, or does that interest date back to longer than the process of researching and writing this book?

Brad Fox: It is kind of a 20 year story, but with a lot of downtime. There was a moment when I came across, by chance, just a few paragraphs from William Beebe’s 1934 book, Half Mile Down, which was a popular nonfiction book written at the time of the bathysphere dives. I came across this couple of paragraphs where he was describing coming up for the first time out of one of the longer dives and emerging from the bathysphere back onto the deck of the barge and being in the afternoon sun in Bermuda after being a couple hours in the darkness of the deep ocean.

That’s where he said this line that I quoted in the first section, that the yellow of the sun “can never hereafter be as wonderful as blue can be,” which I misremembered when I thought about it later as “I saw a blue so blue, the yellow of the sun will never be the same.”

I had this idea of the deep ocean as this kind of transformative crucible. I wrote some short stories based on that idea here and there, and then I had an encounter with a science historian who happened to be working in the archives, who took me up to the Wildlife Conservancy Society archives and kind of started to introduce me to the breadth of the material. That was when I saw that there was a book that needed to really show how wide-ranging and complicated this story was.

Did you always know that Beebe was going to be the primary focus or was there a question of how much you wanted to use him as the focus versus some of the larger issues that you were asking?

I think about it in the sense that I knew that I didn’t want to write a book about Beebe necessarily. I mean, it’s not that I don’t care about Beebe, but obviously he’s the person that is recording and is going through this process. And so what Gloria Hollister was writing down were Beebe’s observations. But as I wrote it, I also wanted to show that this is a story of a community in some way of people that involves a lot of different kinds of people, from these like billionaire socialists and conservationists and eugenicists, to groundbreaking female scientists and writers and artists and a queer community and a mixed-gender community that was not typical of the time. So I wanted to spend as much time as I could balancing an interest in Beebe with showing that everything that was around as well.

Earlier, you were talking about Beebe’s book about going into the deep, and it wasn’t much later that John Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez was published. Was there a larger appetite in the mid 20th century for sort of books in the vein of “I went on a boat and did scientific research”? Because that, as a sub-genre, seems to be completely absent nowadays.

I think in some way, this was a moment of American expansionism and so to me — for all of its beauty and all the reasons that I felt like it was worth writing about and celebrating — that aspect of it there is also inseparable from conquest.

There’s a way that Beebe would be going to Haiti and doing projects there. And that’s inseparable from the American political context. At the same time, there’s a way that going to the depths of the ocean is a way to bring that into American science in a certain way, you know? And as he traveled around the world, he was always supported by, in a certain way earlier in his career, vestiges of the British empire.

He’d go to Borneo and he’d be hanging out with some Englishmen out somewhere, who were complaining about the natives. It was part of that history. And so that’s definitely a matter of that time, which we could argue about whether it’s changed.

One of the things I noticed while reading this book was the way that the story of Beebe and his research was the way it overlapped with other important historical figures — including Theodore Roosevelt and Franz Boas, who I know from his role in Zora Neale Hurston’s career, and the writer Lord Dunsany. How much of that were you able to get from your initial readings of Beebe’s work and how much of that emerged from going through the archives?

The incredible, entangled stories that surround the dives were definitely discovered piecemeal as I was looking into it. First of all understanding the illustrations and different artists and then the way it touches on these side stories. It was a process of discovery that went on and on and on.

I was well into the book before I understood the connection with Marie Tharp and the mapping of the bottom of the ocean and how that was inseparable from this story that I was telling. There were all of these things that just came out in the process of researching.

Are all of Beebe’s archives in one place, or did you need to visit multiple collections?

The first archive that I visited was the Wildlife Conservancy Society, which is in the basement of the administrative building of the Bronx Zoo. There was this wonderful couple of weeks where I was biking over from Harlem where I live and locking up my bike and saying hello to the animals or whatever.

I was going into this old safe downstairs where these documents are kept. Beebe’s personal papers are in Princeton; Jocelyn Crane who was with him in the last decades of his life brought everything there for whatever reason. Gloria Hollister’s stuff is at the Library of Congress. And a friend of mine, a science historian, had given me some of that material before and then I was intending to go to Washington and I got caught in the lockdown.

Early on in lockdown, I got caught in Peru. I was one of these Americans that were stuck in Peru during lockdown. I ended up being there for over a year. Luckily, I had just kind of hoovered up a bunch of material from Princeton and from the Bronx, and then was still intending to do some other stuff. And then one of the librarians at the Library of Congress was kind enough to scan the rest of Gloria Hollister’s material and send it to me.

I was sitting in the jungle unintentionally, with a secondhand laptop that I bought because once I realized I was stuck there long term, just pulling things off Dropbox and writing. That was a lot of the process.

Did spending more time than you’d anticipated in Peru result in any changes on the finished book?

I wouldn’t have intended to write about the earlier parts of Beebe’s career, where he spends time in the jungle, except that being there, eventually it just made sense to work on that material. I started spending more time reading these earlier books of his that described that and getting drawn into that material. And thinking about the ocean and the jungle — these different natural environments that formed the world of those scientists, because Gloria Hollister had also spent time in Guyana.

Before working on this book, I used to call spending time in archives “archive diving.” Not that I’m the only person who says that, but there is a feeling of diving into archives. So there’s a kind of bathyspheric experience in that, I guess.

In terms of finding the drawings and the paintings that are in The Bathysphere Book, was that its own form of archive diving or did that flow pretty directly from the other work you were doing?

That all came right at the beginning in the sense that I had been working on these little like short stories, kind of fictionalizations of this world, when I met this science historian named Katherine McLeod, who was at that time curating a show of Else Bostelmann at the Drawing Center in New York, which went up in 2017.

In the course of that happening, I got to see all this work and then with her, I started to go up to the archives. Most of the work that they were showing was stuff that was from the WCS archive. Later, I would see other Else Bostelmann material that was in Bermuda and other places, but primarily all of the illustrations that are in the book come from that same archive.

There was a moment at the beginning, where the idea was that I was going to edit the log books and Catherine was going to do a selection of images. We were going to write an introductory text and just make a little book like that. But then as I started to uncover more and more of these stories, I realized how much there was to say about this that it needed a richer treatment.

One of the things about the logs, as they’re reprinted here, have a poetic quality to them that’s incredibly evocative.

As soon as you start getting into this material, because some of [the logs] are in Beebe’s book Half Mile Down, as soon as you start to look into that. And also Beebe’s just a fabulous writer. That was definitely one of the original sparks that made me interested in this material.

The 10 Books You Should Be Reading This May

From a deep dive into Steely Dan to a journey into the ocean depthsHow did researching and writing this book change the way you thought of Beebe over the course of the project?

I went through different phases. Just at the beginning, I found his language beautiful, and that means a lot to me. But there was definitely a kind of resistance for me to writing about some gallivanting, white American mid-century dude. That wasn’t what I was really attracted to. And it was in a way, as I got more into the world of that, the complexities of it, that I found it to be something that was — not that I liked him better, but I just thought it was a story worth investigating and representing in some way.

And then I went through these different periods with him. He can often be simultaneously charming and annoying in some way. And then once you get into the darker side of the whole story and his friendship with Roosevelt and Madison Grant and all of what that represents, I started to think about that aspect of the legacy of white America that we live in.

And then, having drawn that out, I came around to like him better towards the end of working on it. Coming across that letter that he signed to Congress, that was an anti-racist letter that he signed with several prominent Black Americans, for example.

As a young man, he wrote an article called “Savages and Children,” which is deeply racist and white supremacist. And then by the end of his life, he will say things like, “If there was supremacy” — I can’t remember what now was the exact line — it’s like, “If one of us was better than the other, it was shared equally,” or something like that. So he modulated his views over the course of his life.

It’s frustrating that, on one hand, he was able to recognize some of the things he got wrong — but he also maintained a friendship with Madison Grant, who was a eugenicist and a white supremacist. Beebe could recognize some of what he got wrong, but he couldn’t make that other leap.

Right. He still dedicated Half Mile Down to Grant in 1934.

Have you yourself done any sort of diving or travel into the depths of the ocean?

A little. I had done some snorkeling, but not too much. But over the course of writing the book, I did get certified as a diver and did some diving in different places. And when I finally went to Bermuda, I did some diving there. The barge that the bathysphere dives launched from is sunk in St. George’s Harbor in Bermuda, but it’s pretty shallow, so you can actually dive around.

You don’t need scuba gear to visit it. You can kind of stand on it if you want to, but it’s surrounded by tropical fish, and it’s pretty amazing, this rusted barge. I met the granddaughter of Captain Sylvester who captained the dives and had an incredible moment hanging out with her and then going down and diving around the wreckage.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.