Looking back at a year in reading is never easy. There’s always another book you could have read, another (metaphorical) world you could have visited. Having come up with 10 best books of 2022 for this list — five works of fiction, five works of nonfiction — I’m already second-guessing it. There isn’t one trait that brings these books together — some are part of a satirical literary lineage that includes Kurt Vonnegut, while others harken back to the ever-searching aesthetics of John Berger and Vivian Gornick.

If these 10 books have anything in common, it’s an attempt to reckon with the present moment without losing hope. Some of these narratives travel back in time; others look to the future, whether technological or organic. They represent an outstanding array of points of view — and each, in its own way, is hard to forget.

James Bridle, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence

James Bridle’s 2019 book New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future was one of that year’s most resonant works of nonfiction — exploring the ways in which the promise of the internet has become something more menacing. Bridle’s new book Ways of Being takes an even grander scope as its subject, with one foot in cutting-edge technology and another in the ways scientists have observed the natural world. Bridle isn’t just considering the question of whether other creatures on the planet are sentient; instead, they’re exploring the very nature of intelligence, from single beings to whole ecosystems. Thought-provoking in the best sense of the phrase.

Percival Everett, Dr. No

The phrase “a writer’s writer” comes to mind when discussing Percival Everett, who’s been writing engaging, relevant and expansive novels at a stunning pace over the last few decades. In recent years he’s gotten wider attention — Telephone was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, and The Trees was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. As you might guess from the title of his latest novel, Dr. No is something of a riff on spy fiction, with one of its two central characters being a man who’s decided to become a Bond villain. And if that’s all that this book was — a talented writer riffing on spy fiction tropes — that would be reason enough to recommend it. Instead, Everett also juxtaposes harrowing moments from American history with existential thrills and comedy, making for another singular work from a writer who specializes in them.

Charles Elton, Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and the Price of a Vision

When we talk about Michael Cimino, it’s largely within the context of two films — The Deer Hunter, an epic about a group of friends who leave a working-class town to fight in Vietnam which features a staggeringly good cast, and Heaven’s Gate, considered by some to be the last gasp of an auteur-friendly studio system. Both films were directed by Michael Cimino, with the latter having a seismic effect on his professional reputation. At least, that’s what’s generally believed. What Charles Elton covers in this biography of Cimino reveals a much more complex figure — and might just leave you rethinking your preconceived notions of him.

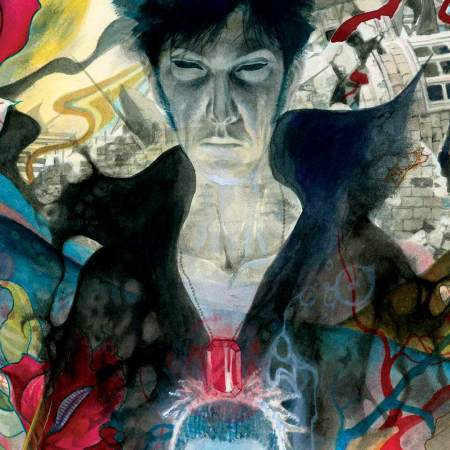

Alan Moore, Illuminations: Stories

2016 saw the publication of Alan Moore’s massive novel Jerusalem, which zeroed in on the city of Northampton to tell a story that was about, well, everything: art, family, industry, the afterlife, the cosmic, you name it. It’s a fine book, but it also (in this critic’s opinion, anyway) featured Moore at both his most appealing and his most frustrating. The stories found in his new collection Illuminations focus much more on the former, with a range of styles on display encompassing haunted memory pieces and formally inventive folk horror. The short novel “What We Can Know About Thunderman” finds Moore drawing on his background in comics and unearthing disquieting histories, eventually winding up at a jaw-dropping place.

Ben Davis, Art in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis and Cultural Strategy

If you’ve been keeping an eye on the art world over the past few years, you’ve probably noticed it intersecting with technology in unexpected ways — the popularity of NFTs being but one manifestation of that. As he demonstrated in his earlier book 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, Davis — the National Art Critic for artnet News — has a skill at finding the nuances in complex situations. And the place where art, technology and large sums of money all converge is very much the picture of a complex situation. Davis offers a memorable guide to the present moment, alongside a few paths for where his areas of coverage might end up before long.

Mark De Silva, The Logos

Do you like your fiction with a heavy dose of ambition? You might notice that the title of Mark De Silva’s second novel could be read in two different ways: logos as in the concept of a principle of reason, or logos as in, well, the things you see on billboards and virtually everywhere around you. In telling the story of a frustrated artist whose life becomes intertwined with a company that might be a smart-drink manufacturer, a distillery or something entirely different, De Silva explores grand themes both classical and eminently modern. This is a novel with plenty to say about art, intimacy and the shifting boundaries between “personality” and “brand.”

Sofia Samatar, The White Mosque

Sometimes writers can surprise you. The bulk of Sofia Samatar’s work to date has taken the form of immaculately-detailed fantastical and speculative fiction. (If you’re an Ursula K. Le Guin reader, you’ll likely find a lot to enjoy in Samatar’s fiction as well.) But The White Mosque represents a very different side of her literary work. It’s a work of nonfiction that follows Samatar as she retraces the steps of a group of 19th century Mennonites who embarked on a long journey that ended with them settling in what is now Uzbekistan. In telling their story, Samatar chronicles elements of her own life, revisits the horrors of Stalinism and ponders the history of photography. It’s an expansive voyage worth taking.

Mat Johnson, Invisible Things

Mat Johnson’s novel Invisible Things opens in the near future, where a crewed mission discovers something unexpected on one of Juipter’s moons — a thriving human civilization, populated by people (and the descendents of people) who disappeared mysteriously over the years. And, as the novel’s title suggests, there’s something else there as well, but it’s not exactly easy to see. Invisible Things is a finely-tuned work of speculative fiction, but it’s also a fantastic example of incisive satire — laugh-out-loud funny at times and capable of summoning primal dread at others.

Ari M. Brostoff, Missing Time: Essays

In their debut essay collection, Ari M. Brostoff reckons with a host of daunting subjects, from what it’s like to watch The X-Files in an increasingly paranoid time to the legacies of Philip Roth. Brostoff is equally at home summoning up a sense of place and making insightful observations on pop-cultural subjects familiar and obscure. As a statement of just what its author is capable of, Missing Time is a powerful document of one writer’s areas of expertise.

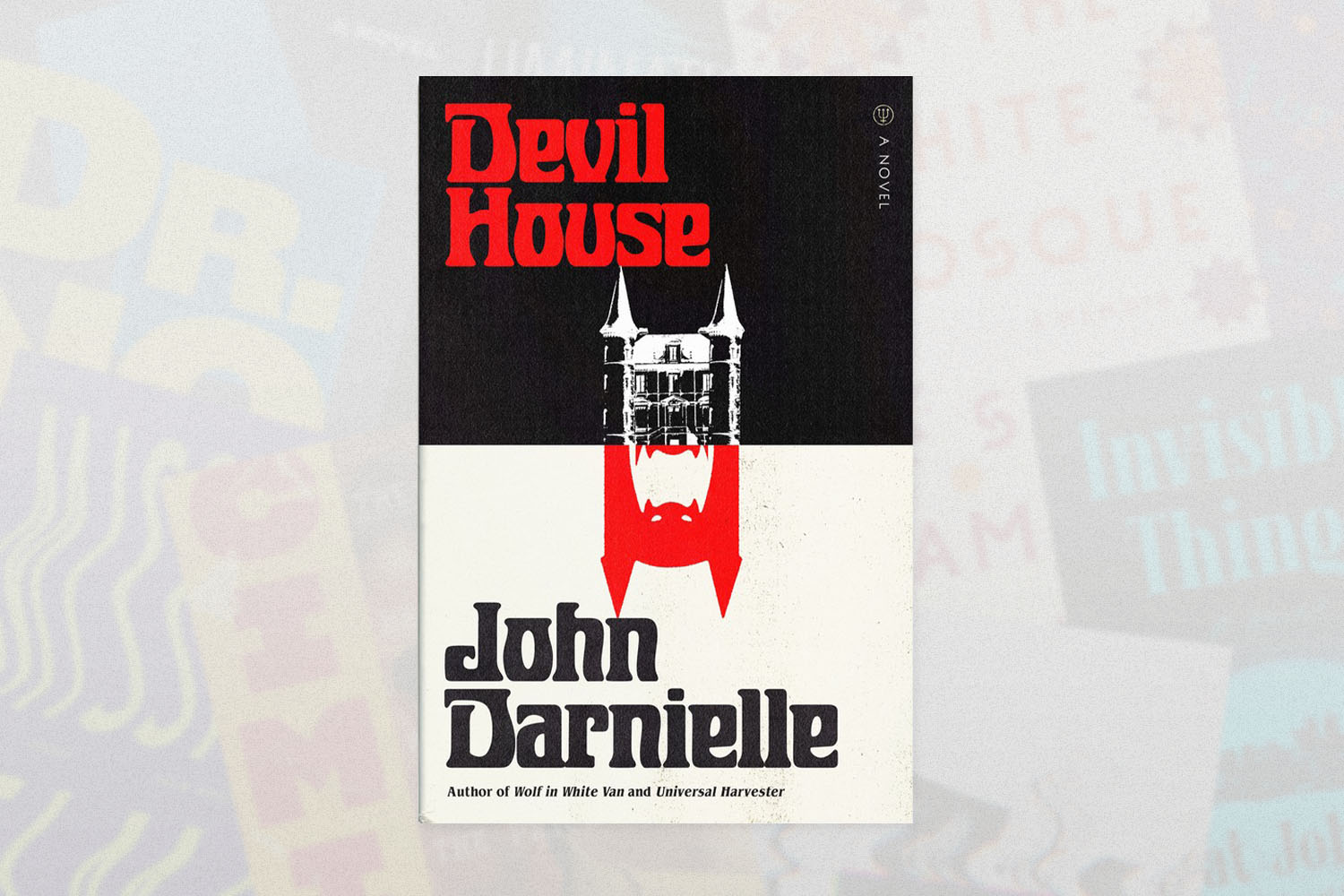

John Darnielle, Devil House

In addition to his rightly acclaimed work as a musician and songwriter, John Darnielle is now four novels deep into an engaging and challenging bibliography. Devil House features plenty of societal outcasts and frustrated youths, but Darnielle tells their story here through a very specific lens, one which also reckons with some of the ongoing debates taking place around the ethics of true crime journalism. In telling the story of a building that may be the scene of a horrific crime, Devil House wrestles with big questions, even as it also pulls off some deft structural maneuvers.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.