Browsing through the rock section of a record store in 1972, you’d see a wealth of abstract cover images: an exploding blimp on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s 1969 self-titled debut, an ear underwater on the cover of Pink Floyd’s 1971 album Meddle.

Such a style was de rigueur for “serious” rock bands at the time, this look of “very hip, almost coded things that underground, long hair people would get,” laughs Simon Reynolds, author of Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the Twenty-first Century. And yet there was something about Rita Hayworth that appealed to Bryan Ferry, the way the 1940s pinup lounged on satin sheets, hair cascading in waves behind her, a soft smile on her lips.

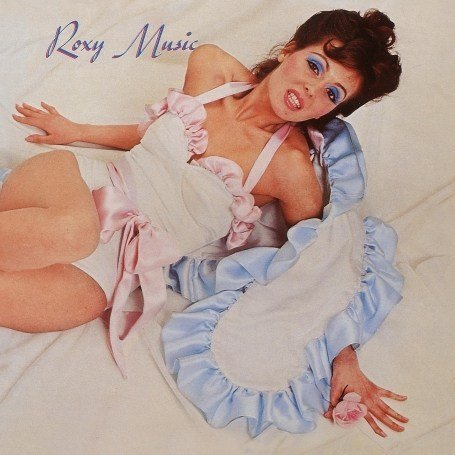

The image would have been some 30 years old by the time Ferry saw it. Yet in a sea of conceptual album covers utilized by early prog and metal bands, he saw something in the old pictures of the actress and model that he wanted for his own band, Roxy Music: her glamour, mystery and sensuality. He captured those feelings and updated them for the 1970s, placing a pinup shot of model Kari-Ann Muller done by photographer Karl Stoecker front and center on the band’s debut album in ‘72. Attired in a custom creation by fashion designer Antony Price, Muller, like Hayworth, leaned pinup-style on rumpled sheets, frothy in pink, blue and white ruffles. “It was meant to look like a Neapolitan ice cream,” Price told Another Man in 2017. “I was inspired, of course, by Hollywood,” Ferry said later, in a 2013 conversation for Paris’s Le Bon Marche department store, “but we always liked to think we were making something new out of that.”

Roxy Music’s album art would become the antithesis of the cryptic rock cover: instead of geometric orbs, a seductive, curvaceous woman; instead of a bold color palette, a smattering of pastels; instead of abstraction and metaphor, something a bit more literal, not to mention one of the first statements of retro-ironic style Reynolds says would later inspire everyone from Phil Collins to OutKast. Roxy Music espoused what rock considered its opposites — showbiz, musical theatre, Las Vegas, Hollywood — while still maintaining sensibilities considered native to rock at the time: liberated sexuality, musicianship and bravado.

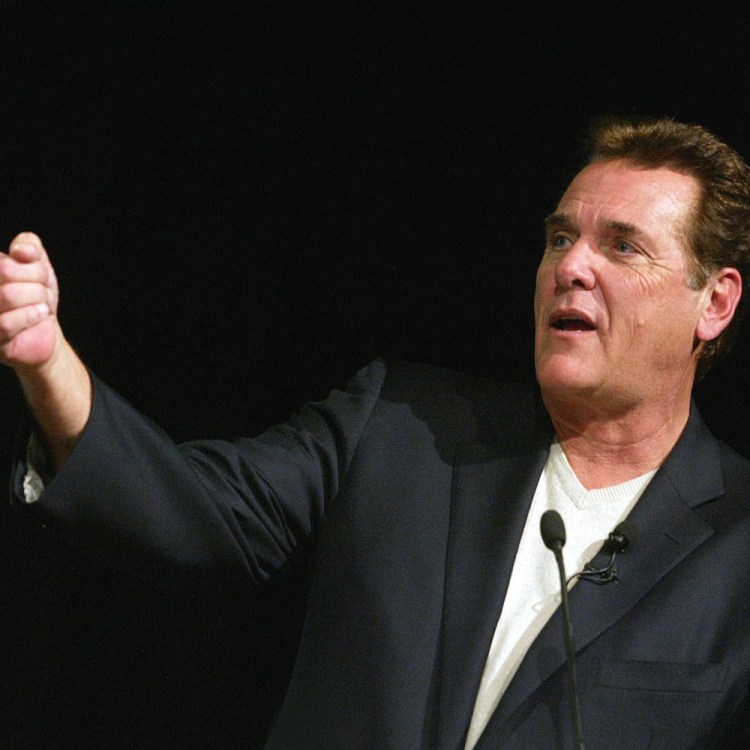

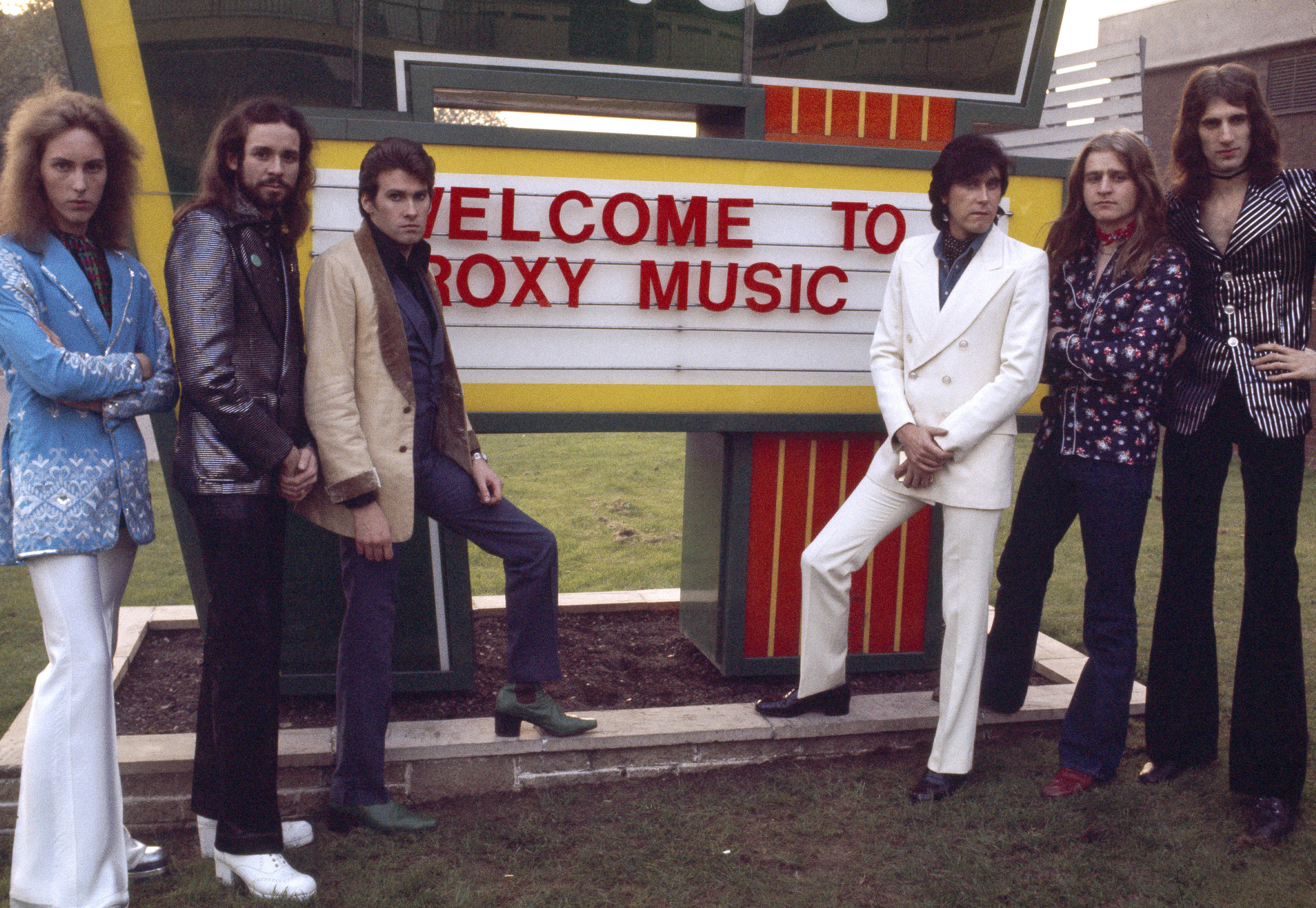

Such a move could come off as pure cheese, but because Roxy Music’s sound intellectualized the image, it was a risk that worked. This year, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, 47 years after their first album debuted, 45 years after their legendary album Country Life was released. The debut started off one of the greatest runs in album cover history; the look was just as important as the sound.

Ferry was inspired by the Velvet Underground, whose art-pop crossover sensibilities were informed by the pop art of Andy Warhol and his ilk. The band’s debut reflected this sonically and visually. Through almost five decades, the band developed a sound at once nostalgic — informed by everything from 1930s ballads to 1960s psychedelia — and forward thinking, using the (then) very modern synthesizer. In doing so, they became glam rock forefathers.

“Roxy is a postmodern band,” Reynolds says. “From the lyrics, to the clothing they wore, to the album artwork, to the music, it was a composite of elements from different eras, things being combined with a sense of irony and collage.” It was an aesthetic that was also reflected in what are arguably their greatest album covers, those released between 1972 and 1975.

From an early age, Ferry sought glamour, an escape from the monotony of 1950s life and his working-class background in the town of Washington, county Durham, in the U.K. By the 1960s, he developed a love of American R&B and played in bands while in high school. Studying art at Newcastle University, Ferry was mentored by Mark Lancaster, a screen-printer for Andy Warhol, and the artist Richard Hamilton, who developed an attitude critical of pop culture and consumerism in the 1960s that would become the foundations of the pop art movement. Hamilton viewed artists as participants in and even creators of mass culture, allowed to be inspired by its visuals.

These ideas would run so deeply through Ferry’s work as a fine artist and musician that Hamilton would later call Ferry “my greatest creation.” After graduating college, Ferry tried out to be the vocalist for the prog band King Crimson, but didn’t make the cut. Around that same time, in 1970, he formed Roxy Music, advertising for musicians in local papers taking on Mackay as saxophonist and oboist, and “non-musician” Brian Eno on synthesizer and tape effects.They played live and recorded their first demo in 1971, eventually winning the praise from tastemakers like BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel. The first album made a small splash commercially, but the people it influenced — from David Bowie to Duran Duran — make it one of the most important debuts of the decade,

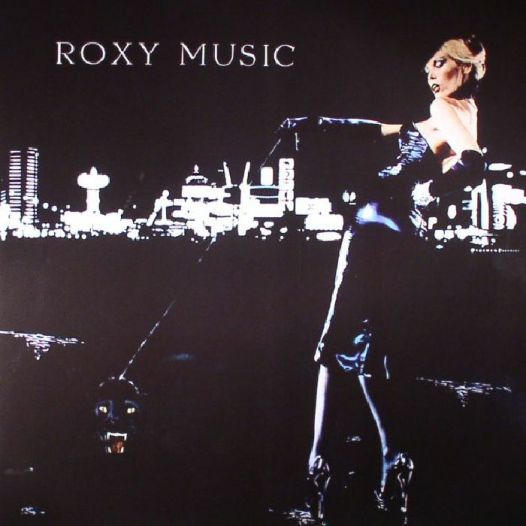

Roxy Music would continue their embrace of irony and allure from their self-titled debut on their next album, 1973’s For Your Pleasure. French model Amanda Lear would be Ferry’s muse this time, “a panther-woman getting out of a car” as the singer told Le Bon Marche. The futuristic, neo-noir, high-fashion cover was shot again by Stoecker, with Lear in a shiny, Price-designed black dress and fur in front of a futuristic city, which Ferry said was actually a manipulated image of Las Vegas. Ferry, dressed as a chauffeur in another Price design, leaned near a Cadillac on the back side of the album.

“It seemed to capture the mood of that time really well without us trying to do that,” Ferry also said to Le Bon Marche, of the way they wedded artifice with simplicity. “It brings out the impossibleness of glamour,” Reynolds says, Lear’s body contorted and curvaceous while wearing death-defying heels. Lear remembers the album cover as a tribute to Hitchcock blondes, Kim Novak in particular. Making friends with the band was “a delicious experience,” Lear tells InsideHook via email. “But I never imagined that almost 50 years later this album cover would be such a cult [classic]!!…The attitude and the look stuck to me for many years and contributed to the launch of my career.”

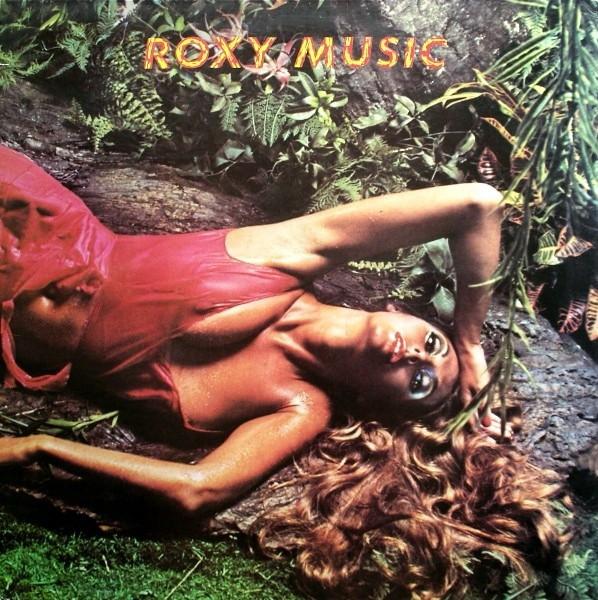

Roxy Music’s cover trademark had become beautiful women, a theme which carried over to 1973’s Stranded. Ferry sought out Marilyn Coles, Playboy’s January 1972 Playmate of the Month, for the album cover. She appears as if lost in the jungle, soaked and draped in a ripped red dress. Deviating from earlier attempts at high fashion, the Stranded cover, also shot by Stoecker, is a soft-core response to hard-core pornographic imagery that started filtering out from seedy theatres after 1972’s Deep Throat achieved international fame.

The film ushered in the age of “porno chic,” where an increase in production value in pornography meant an improved plots and visual possibilities. With this, porn’s edginess and taboo drew fashionable crowds: 1972’s Behind the Green Door screened at the Cannes Film Festival, for example. And the term “porno chic” itself was coined in The New York Times Magazine, which cited 5,000 visitors weekly to a screening of Deep Throat in New York, among them the likes of Johnny Carson and Jack Nicholson. Perhaps accordingly, the timing was right for Roxy Music to do a cover like Stranded. “Roxy Music did their work … at the intersection of desire and consumerism and glamour and fantasy,” Reynolds says. “A lot of their songs are about that, about impossible ideals, impossible desires.”

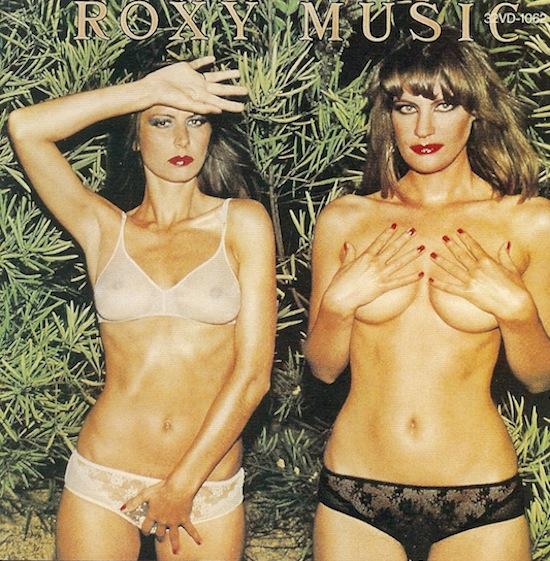

This fascination continued with the band’s acclaimed 1974 album Country Life. At once a reference to a high-end British lifestyle magazine, Shakespeare’s use of “country matters” in Hamlet as a euphemism for sex, and an obscene pun all rolled into one, the album cover featured a significantly less soft-core porn shot of German tourists Constanze Karoli and Eveline Grunwald. In barely-there lace lingerie and glossy red lipstick, the models stood as if caught; city girls running away from a country party, electrified with flash. The visual was inspired by the Profumo affair, in which a 19-year-old model named Christine Keeler became tangled in a dalliance with British politician John Profumo: the celebrity, the seediness of it all.

Originally, photographer Eric Boman says that the models they planned to work with departed early. He and Ferry needed a new plan. They approached Karoli and Grunwald in a bar and explained their predicament. The women obliged. “The idea was to beef out the album’s title by visually creating a country-house orgy atmosphere in a way that would just pass the board of censors,” Boman tells InsideHook via email.

“Over wine and German cold cuts, we worked out a plan where Antony [Price] would go to the nearest town and pick out some slutty underwear. Scouting the villa’s garden, I found a thicket of greenery that could provide a visually neutral backdrop for two girls looking for trouble and getting caught in the headlights of a car — hence their attempt at decorum. That also took care of the lighting since I had no equipment other than my camera.”

The album cover caused a stir because the models’ sheer lingerie left little to the imagination. It was censored in the Netherlands, and was released sans models in the U.S., reissued later with the proper cover. It was that classic Roxy collage of high and low culture, filth and glitter, even though this particular cover is still regularly listed among the most risque album covers of all time.

Far less scandalous is the album cover of 1975’s Siren, which features supermodel Jerry Hall crawling across the rocks of a Greek Island. A golden crown sat atop Hall’s long blonde mane, recreating her as the treacherous siren, luring sailors to death. Shot with a blue filter by photographer Graham Hughes, Antony Price also painted Hall’s body and long, pointy nails blue, adorning her ankles with blue fins. It’s a detail Price attributes to an obsession with Marvel Comics’ Dorma, a blue aristocrat from the underwater world of comic Namor the Sub-Mariner. Hall had already modeled for Revlon and Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium perfume, but her presence on their cover skyrocketed her to fame. It was during this shoot that Hall fell in love with Ferry. They became engaged within months, but Hall would soon leave him for Mick Jagger. Both steeped in the past and swirling with the drama of the present, Siren is another reflection of Roxy Music as a band.

It was after Siren that Roxy Music’s albums deviated from their traditional sultry cover girls. Manifesto was made in 1979 after a four-year hiatus, a temporary breakup in which members worked on solo projects, and represented the greatest departure. It featured a soirée of mannequins male and female in addition to two live models hidden amongst the crowd.

The following album, Flesh and Blood, featured three beautiful women (two on the front cover, one on the back) who were not so much purposely eroticized as they were revered with powerful stature. The same goes for the cover of the band’s last album, 1982’s Avalon, which features Ferry’s future wife of 21 years, model and socialite Lucy Helmore. In a pose descended from Arthurian legend, she faces a sunrise, horned helmet and falcon at the ready as if visiting Arthur’s Avalon herself. She married Ferry a month after the album came out, pregnant with their first child, Otis.

In the seven years between Roxy Music’s hiatus and Avalon, the feminist movement had developed a strong public voice on both sides of the pond. Perhaps with that, the band decided to change their album cover m.o. Or, with the introspection of solo projects, the sophistication of later albums (“Ten years after its debut, Roxy Music has mellowed,” Kurt Loder wrote in Rolling Stone upon Avalon’s release in 1982, “but the sound is softer, dreamier and less determinedly dramatic now”), and the chronology of their own personal lives, perhaps they just grew up.

Now that album art is the tiniest fraction of what used to exist in a 12 x 12 inch frame, looking back at Roxy Music’s album covers is a reminder of what was in both aesthetics and politics. It’s rare to see a beautiful woman who’s not the musician on an album cover given how our conversations about objectification and representation of women have changed. Then, as much as Roxy Music’s album covers are rife with the oft-contested male gaze and certainly put women in some compromising positions, they show how much control a band could have over their visual presence in the world, something fairly new at the time. And the visual Roxy Music wanted to share was not an abstraction, it was something tangible: beautiful women, adventure, a life beyond what you had now. As Reynolds puts it, “Their image was ‘We’re on the way up’ and that was the fantasy they were selling.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.