Heads up: Some of the images in this article might be considered NSFW.

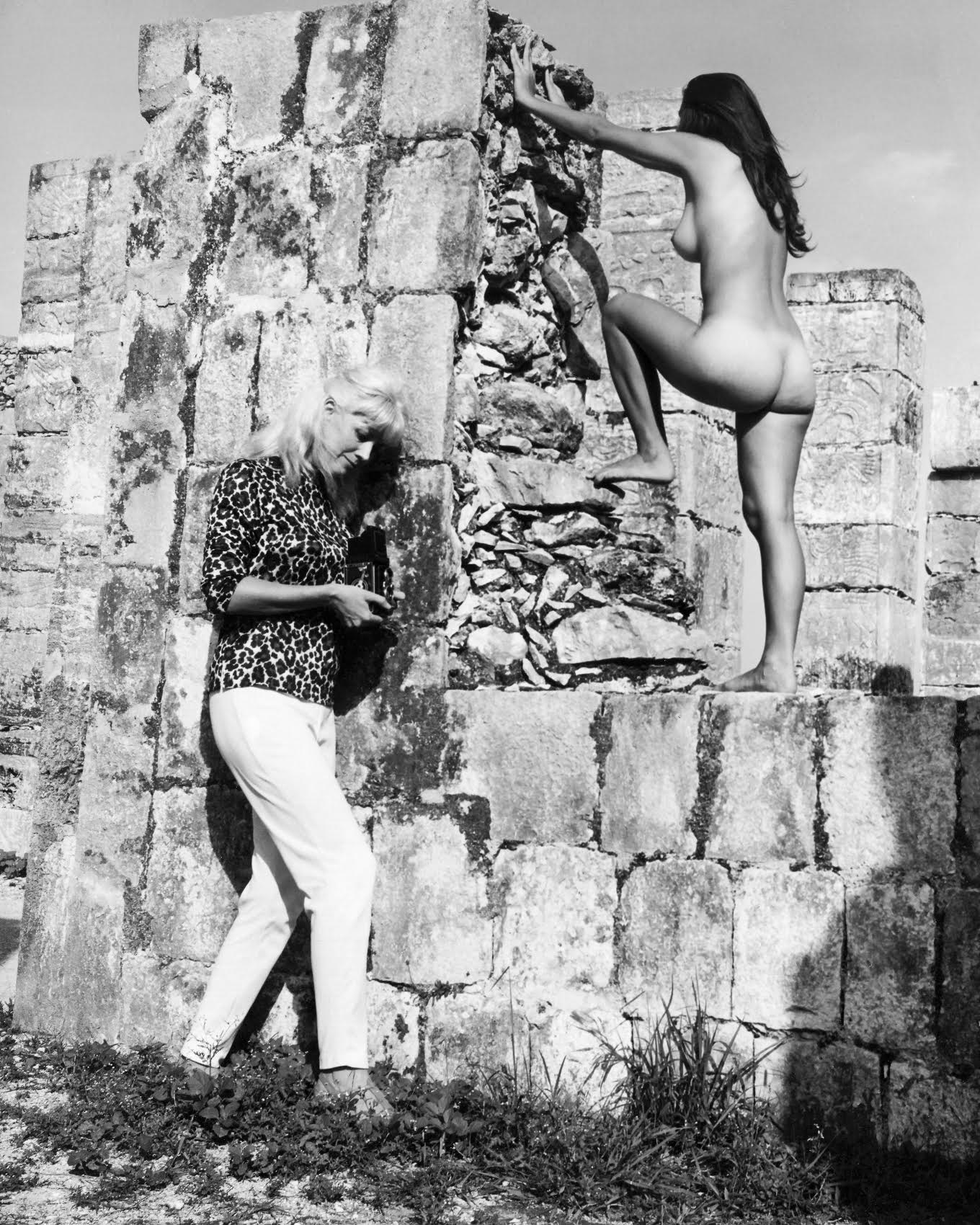

Among the ruins of Mexico’s Chichén Itzá, Christine Starr angles her lithe, naked frame toward the rising sun. With the sky crayon blue behind her and the grass green under her feet, she is radiant.

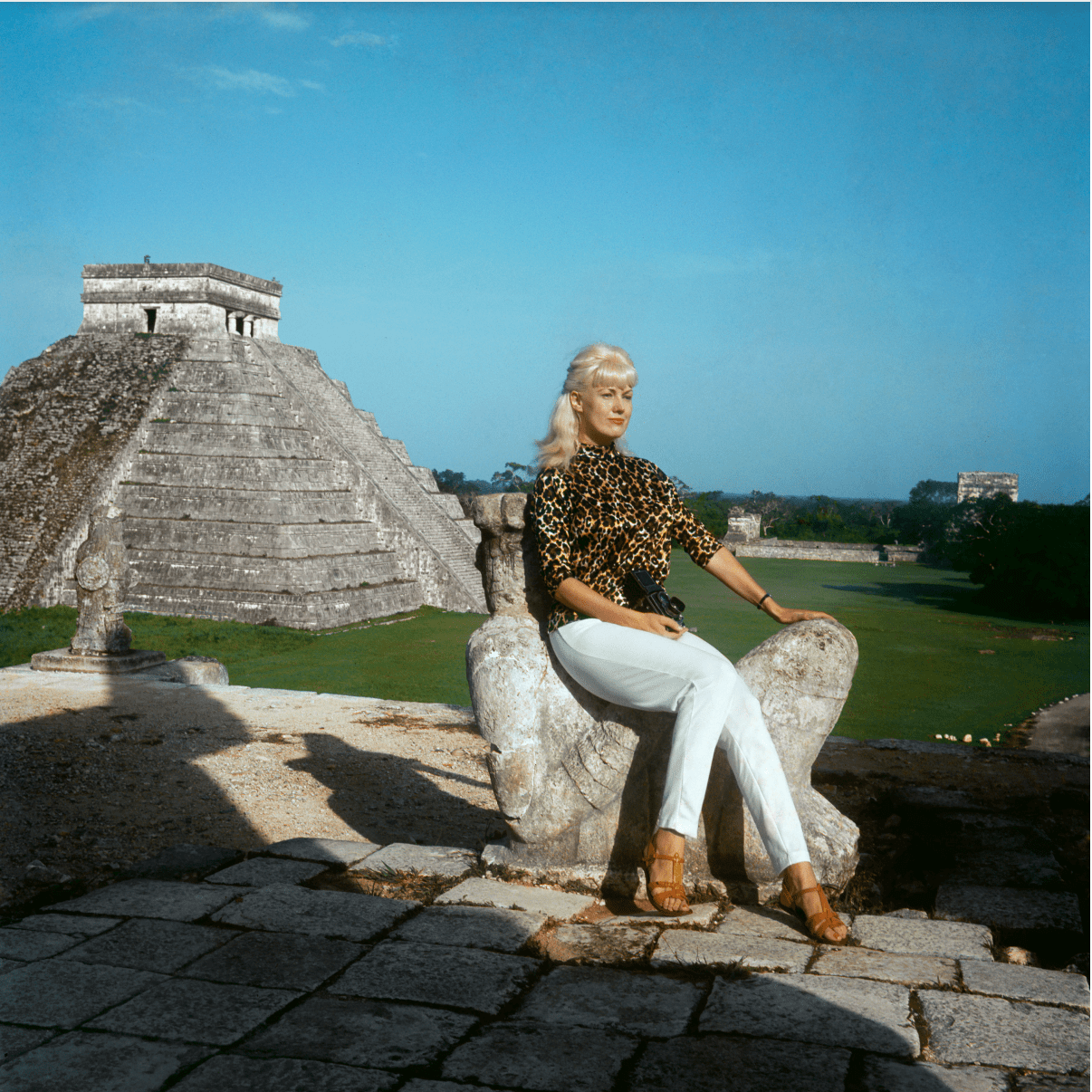

Nearby stands another bombshell, though this one’s behind the camera, and more modestly clothed (which is to say, clothed). Holding her signature Rolleiflex camera, Bunny Yeager is a bleach-blonde with bangs and red lipstick, leopard top and white cigarette pants. Once called the “world’s greatest pinup photographer” by none other than Diane Arbus, Yeager enjoyed a 60-year career photographing beautiful women around the world, among them legendary pinup Bettie Page in Miami and Ursula Andress as Bond girl Honey Ryder on the set of 1962’s Dr. No in Jamaica.

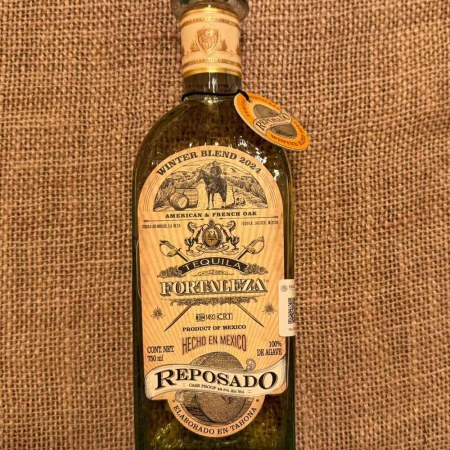

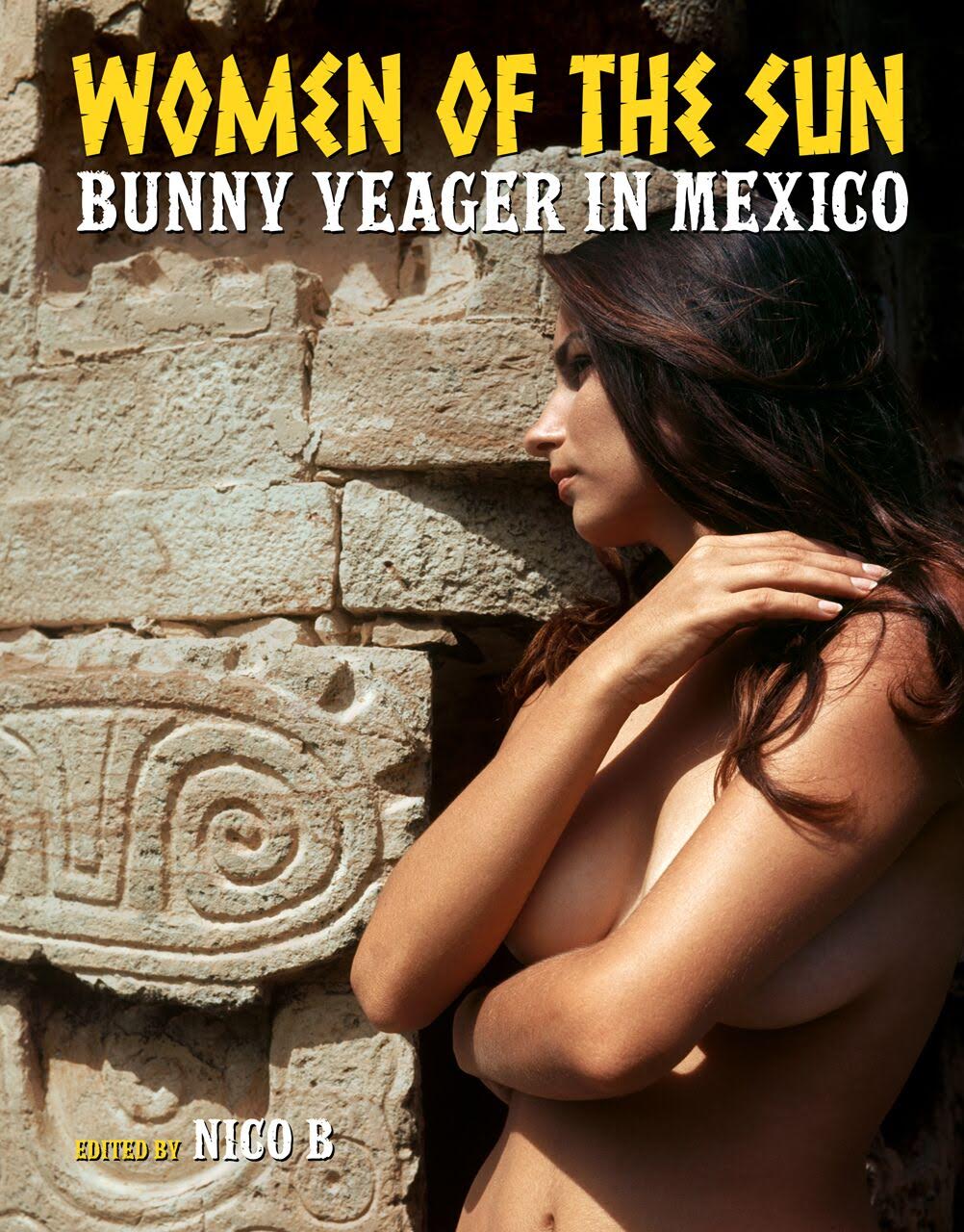

But Yeager’s images from her time in Mexico remain the most unknown. That is, until publisher Cult Epics releases Women of the Sun: Bunny Yeager in Mexico on June 9.

Bunny Yeager worked almost until the day she died in 2014, at the age of 85 — in fact, two days before she was taken to the hospital where she eventually passed, she had been photographing former Playboy Playmate Claire Sinclair. It was among Yeager’s last wishes to see her images from Mexico turned into a book.

Yeager was granted admission to shoot at Chichén Itzá and its nearby temples early in the morning, before tourists arrived. It was then unheard of to shoot nudes there, if permitted at all. “They were surrounded by soldiers,” Yeager’s daughter, Lisa Irwin Gilbert, writes in Women of the Sun. “And they had to be very careful too, trying to sneak in and get these pictures of the model making different poses around the pyramid. If one of the soldiers had seen them, he would have taken the film out of the camera and destroyed it, and everything would have been lost. But they were lucky nothing happened like that.”

Instead, Yeager ended up with 1967’s 100-page paperback Bunny Yeager’s Camera in Mexico, a black-and-white photographic tour guide that featured architectural photography, street photography and some occasional nudes. But like any photographer, she shot much more than appeared in that text, and many of these rarely before seen images — in both black and white and color — grace the pages of Women of the Sun, along with some of Yeager’s text from that book. There are images of Christine Starr at the great ruins, of course, but also pinups of women local to Mexico and behind-the-scenes shots of Yeager herself. She was, after all, no stranger to the other side of the camera.

Bunny Yeager moved to Miami from Pitcairn, Pennsylvania — a small town 15 miles east of Pittsburgh — with her family as a teenager. Born Linnea Eleanor, she became “Bunny” after seeing Lana Turner play a character of the same name in the 1945 film Week-End at the Waldorf. After graduating from Miami Edison Senior High School, Yeager took a job doing clerical work at an insurance company during the day, and by night the statuesque (5’10”) and curvaceous (36-25-37) Yeager began at the Coronet School of Modeling.

“I wanted to have the best things in life and I thought by being a model, somehow, that’s the way I would get it,” Yeager told Dazed in 2012. “After we moved to Miami I decided I wasn’t going to let anything stand in my way. I thought, ‘This is the place. I’m going to change my life, I’m going to be somebody else, I’m going to be the person that I always thought I could be.’”

It was the late 1940s, and a postwar Florida was seeking to redevelop its reputation as a tourist destination. Beautiful women were a part of that, as were the photos of them that became popular during the war: pinups or “cheesecake photography,” also called “glamour photography.” A wink, a long leg, a generous smile, a peek of hip or cleavage, just like those painted on planes defending American interests overseas: literal and metaphorical bombshells.

Yeager studied pinup calendars and practiced their poses, and also learned from posing for local photographers. “You learn the walks and the turns, the pivots. I learned about photographer’s shortcomings by posing for them. A lot of them depended on the model to come up with poses, which was ridiculous!” It was a skill she’d remember while working as a model in Miami Beach, where she also designed her own swimsuits. She found the suits of the day too modest and ill-fitting for such a tall woman, so she made her own bikinis with ties on the side, adding to the popularization of a style the remains de rigueur today.

Ever the hustler, Yeager’s career in front of the camera began when she called up the city herself and asked how to be a part of its local campaigns. This work led to Yeager’s image in both high-fashion photography and on the cheesecake postcards popular in the city at the time, the latter of which were published in more than 300 newspapers and magazines. Yeager’s mother also entered her in numerous beauty pageants. By the time she was 20, Yeager had some 30 beauty pageant wins, Queen of Miami, Cheesecake Queen and Miss Personality of Miami Beach among them. One win — 1949’s “Sports Queen” — even saw her crowned by Joe DiMaggio, who later asked her on a date.

As Yeager’s modeling career grew at the beginning of the 1950s, she needed more images for her portfolio. But she regularly found she was dissatisfied with the work of local photographers and wondered if she couldn’t make better pictures on her own. A boyfriend suggested she pose for photography classes to get free images; instead, she ended up taking the classes herself. Shortly after, Yeager ran into renowned photographer Roy Pinney, for whom she had previously posed as a model, and told him about her coursework. He promptly photographed her again and crowned her “The World’s Prettiest Photographer” on the cover of U.S. Camera magazine in 1952. For an early assignment, she photographed Miami model Maria Stinger with two cheetahs at open-air zoo Africa U.S.A. wearing a leopard print bikini of Yeager’s own design. It became her first sale, to cheesecake magazine Eye, for its March 1954 cover. Yeager often photographed herself, too — a favorite image is the photographer with long blonde hair and a high-cut leotard staring into her large-format camera, shutter in hand. A hobby that Yeager had adopted to support her modeling was quickly evolving, and soon it would become something much bigger.

In Spring of 1954, Yeager received a phone call from a model named Bettie Page. The iconic model had been doing fetish shoots in New York at the time and developed a following in such circles. Yeager hired her sight unseen because she was willing to do nudes, a subject the photographer had never worked on before. They collaborated many times throughout the course of 1954, but one particular photoshoot would change Yeager’s life. With the holiday season approaching, Yeager shot Page on a white shag rug in front of a white Christmas tree, nude save for a Santa hat the photographer made. The image became Yeager’s first sale to Playboy, published as a centerfold in the fledgling magazine’s January 1955 issue. Yeager’s aesthetic — clean, wholesome, girl-next-door pinups — matched exactly with Playboy’s at the time. It would become the magazine’s first holiday centerfold, and the first of eight centerfolds Yeager would shoot for the magazine, not to mention several “Playmates of the Month,” some of whom she discovered herself. Yeager also appeared in the magazine as “Queen of the Centerfolds,” shot by none other than Hugh Hefner.

Yeager’s images of Page are considered some of the best ever taken of the model, whether they’re the famed shots of Page in a leopard one-piece with two cheetahs (also at Africa U.S.A.), the images of her nude on a boat, in a bikini at a carnival, or simply playing on the beach. But Yeager’s career outside of her work with Page also flourished. Yeager’s image would appear in Esquire, Cosmopolitan and Women’s Wear Daily, as well as many cheesecake publications. In 1960, she was named one of the top American female photographers by the Professional Photographers of America and would appear in a swimsuit spread in LIFE magazine.

She had truly arrived, and not in a small way. She became a celebrity of sorts, featured on game shows like What’s My Line? (beginning at 20:03 … “she’s obviously a typical American schoolteacher,” the actor Martin Gabel posits, deliciously incorrect), I’ve Got a Secret and To Tell the Truth. In her career, Yeager would also publish some 30 books featuring her own photography in both collections and how-tos. Her bestselling Photographing the Female Figure sold more than 300,000 copies after it was published in 1957, and her book How I Photograph Myself led to her (23-minute-long) appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1966.

As a woman, her role as a photographer of any kind, let alone as a pinup photographer, made her extraordinary. But on top of that, she made her models feel comfortable and safe in a way many male photographers couldn’t, which meant their responses to her camera were often far more joyful and candid. Plus, Yeager was adventurous as far as cheesecake photographers at the time went — many worked only in studios, but Yeager also (and often) shot outside. “She was incredibly adventurous and brave working with models outdoors and shooting in natural light,” says Sarahjane Blum, co-owner of online illustration, art and glamour photography gallery Grapefruit Moon Gallery, which also owns the Bunny Yeager archives (Blum also assisted in assembling Women of the Sun). “You would see a lot of people posed in front of a fireplace or in a boudoir setting, and she’s taking her models to the beach, she’s taking them to amusement parks, she’s taking them to wildlife safari parks to shoot next to cheetahs, and that spirit of adventure is not something that other photographers had.”

When Yeager became a photographer, the field itself was just becoming recognized as an art form — the Museum of Modern Art did not have a photography department until 1940, for example — and the nature of the nude image was still relatively suspect. “Nude photography was really considered to be something where, to make it acceptable, you had to be demonstrating the artifice of it,” Blum says. In the years before Yeager, this meant models “dressed in gauzy fabric as though they were a Grecian statue,” or “posed as if they were on the stage and there was something very distant,” Blum continues. “It wasn’t supposed to be ‘This is the girl you saw walking down the street.’”

While an underground of raunchier, more overt photography did exist — Bettie Page herself participated — it was just barely legal or sold “under the counter” to niche audiences. But Bunny’s images were lively, exuberant and fun. Even her nudes possessed an air of innocence, with models tending to look directly at the camera, coyly. “It was really photographers like Bunny Yeager and magazines like Playboy that brought the conversation of [presenting women] as we see them clothed and celebrate them equally in stages of more and more undress,” Blum says.

But toward the end of the 1960s, those stages of undress had gone just a little too far for Yeager. With the emergence of magazines like Hustler and Penthouse “showing pink” in the age of “porno-chic,” Yeager’s lighthearted images fell out of vogue. Not that she wanted to shoot “pink,” anyway — she felt such publications were vulgar and exploitative. Yeager instead turned her career toward other aspects of photography instead, as well as acting — she appears briefly alongside Frank Sinatra in the 1968 film Lady in Cement.

But every time there’s been a resurgence of interest in Page, an interest in Yeager’s work also reappears. She has even begun to gain recognition from the world of fine-art photography, with some of her pieces displayed on the walls of galleries and museums. In 2010, The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh mounted the exhibition Bunny Yeager: The Legendary Queen of the Pin-Up, which featured images from the 1950s and 1960s. Yeager would also later show at galleries in Miami, Los Angeles, Tucson and other locations across the country and the world. Her images are also still available at Grapefruit Moon and an image of hers appeared in the exhibition, Photography’s Last Century: The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this year. On June 6 of this year, La Luz de Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles is scheduled to show a collection of images from Women of the Sun.

Bunny Yeager’s images, sublimely lit in the outdoors with fill light long before such a technique was commonplace, influenced a generation of photographers, from the aforementioned Diane Arbus to Cindy Sherman to Yasumasa Morimura. A 2015 cover of The Fader starring Rihanna even pays faithful homage to Yeager.

Really, wherever there’s a joyful celebration of the female form, Yeager is present. “Fashion photography is where you show off the clothing,” Yeager said with a smile in a 1965 interview for South Florida television station WTVJ. “And glamour photography is showing off the girl.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.