I didn’t think I’d ever see Andy Warhol wearing a T-shirt, but there he was in a pale blue one on the wall of the Jack Shainman Gallery, the words “Andy Warhol’s Interview” scribbled in his own hand across his chest. The image is one of countless others that have rarely, if ever, seen a gallery wall. But with “Andy Warhol Photography: 1967-1987,” an exhibition that stretches across Shainman’s two Chelsea galleries (one of which is labeled “explicit”), viewers get a look into one of the more underappreciated aspects of Warhol’s work. “I never thought I could get in the door with Warhol as a gallerist. I thought it was too late,” Shainman says. “But what I love doing is not only bringing in artists who are not known from other places, I love to bring in things that haven’t been considered before.”

Given the ubiquity of his work in our collective cultural memory, it might seem impossible that anything Warhol made hasn’t been considered. But the truth is that while photography was central to Warhol’s artistic practice for 30 years, often as source material for his famous screen prints, his purely photographic works — in particular, his stitched gelatin prints of a single image printed multiple times and sewn together — only saw the light of day once while he was alive. That was back in 1987, at a show at the former Robert Miller Gallery in Midtown Manhattan.

In other words, this is a special occasion.

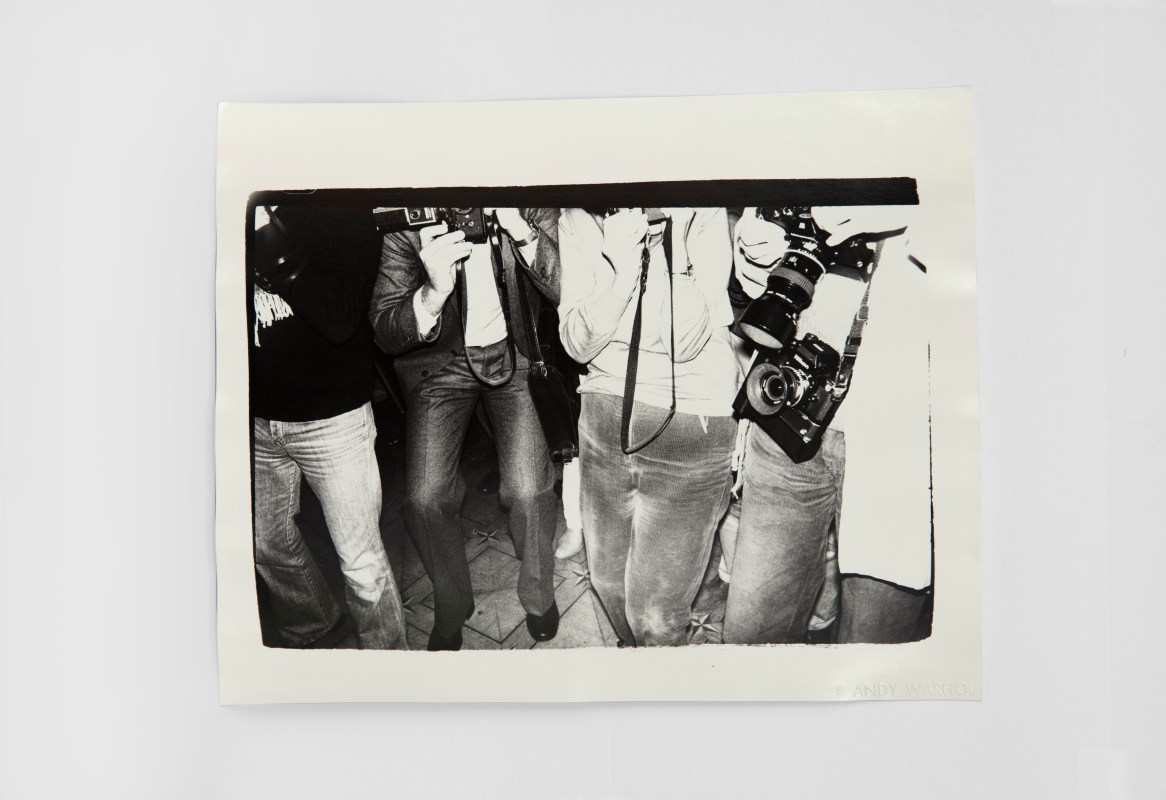

Between 1963 and 1966, Warhol employed photo-booth strips in his work, taken in sex shops he brought subjects to in Times Square. Later in the decade, he carried a Polaroid camera with him (toting it along so often he called it his “date”), but in 1977 he was gifted a Minox 35 El camera by his Swiss art dealer, Thomas Amman. Warhol became obsessed, and shot 35mm black-and-white film on it for the next 10 years. He shot celebrities with it, but also everything from nudes of feather-haired young men to gardens to, yes, bananas, and perhaps would have continued had he not passed away.

What’s interesting about Warhol’s rarer silver gelatin work on view at Shainman, both the stitched pictures and his 8 x 10 prints, is how surprisingly mundane it can be: a bride and groom on their wedding day, a collection of shoes needing repair, a pile of clothes, feet, a docked seaplane, and, eerily, a New Year’s card from 1987 taken just a month before he died. “I always say there’s a Warhol for everybody because, really! He photographed so ubiquitously that everyone can find resonance with something, and you’re like, ‘Oh my God, that’s a Warhol?’” says co-curator Jim Hedges, an expert on and collector of Warhol photography.

Warhol’s 1987 Robert Miller Gallery show went up just six weeks before the artist died in what was thought to be a routine gallbladder operation. At the time, Warhol had planned for photography to be the next stage of his art practice and business. Artists like Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman were becoming known for their photographic artworks, and Warhol was excited to continue experimenting with the form himself. It has since been proven that the surgery was much more complex than media coverage at the time had shown (and, perhaps, than Warhol would let on): with a deep-seated fear of hospitals, Warhol had been in pain for over a month, and avoided surgery far longer than he should have — he had developed gangrene in his gallbladder, which later fell apart in the doctor’s hands. He survived the surgery, but afterward, his heart crumbled under the trauma of it and stopped.

Warhol left behind an unfinished chapter in his photographic oeuvre, one that ultimately featured six different types of image-making from across his career: the Hollywood publicity stills he used early on to make works like his famed screenprint “Marilyn Diptych”; the photo-booth strips; stitched gelatin silver prints, like those at the Robert Miller Gallery show; 8×10 silver prints; Polaroids in a variety of sizes; and photo collages (this doesn’t include Warhol’s black-and-white film work, including his famed “Screen Tests,” which also appear in the exhibition). All those types are on view at Jack Shainman, which makes it among the few shows, if not the only show, to ever highlight such a breadth of the artist’s photographic output. “I wanted to focus on other things … something people didn’t really realize that Warhol did,” Shainman says. “People say Picasso did everything. Well, Picasso did a lot and Warhol did everything else,” he laughs.

Rare collections of Warhol’s Polaroids are also present in the show. In one gallery on West 20th Street, there are still lifes that functioned as source material for screen prints later on. And notably, in the other “explicit” gallery on West 24th Street — alongside his instant portraits of icons like Debbie Harry, Kareem Abdul-Jabaar and Fiat’s Gianni Agnelli — are his images from an aptly titled series called “Torsos and Sex Parts.” There are also photo collages made when Warhol was a guest editor for Vogue Paris in 1984 featuring a very young Jean-Paul Gaultier as well as Keith Haring and William Burroughs all posing with models. The latter in particular is noteworthy because the images are placed onto white paper, as if for a layout, and written on in Warhol’s handwriting.

If you’re thinking some of these images might be priceless, you’d be right: not all of the images in the exhibition are on the market. Shainman was more interested in producing a well-rounded show, one that told the story of Warhol’s work and process, than having everything for sale, he says. So he borrowed images from personal collections, dealers and friends of both Shainman and Hedges (not to mention Hedges himself) to round out the show.

While we’re familiar with Warhol’s images of celebrities — the artist famously quipped that “A good picture is one that’s in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous” — it’s in the artist’s rarer photographic work that we really get to see his voraciousness for image making and obsession with creation. “The rapaciousness of his gaze, the ambition of his study of everything and then his editing, is like the backbone of what makes this artist so interesting,” Hedges says. “I think for sure he considered everything to be a work of art.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.